We conceived of Losing a Twin at Birth as a project that worked with parents to capture their experience of this complex form of grief. Yet the activity of gathering the materials for the inks enabled other family members to be involved.

In my last blog post, I described how the grandparents of one family participated in the project by gathering rose petals from their garden and sending them through the post, so that they could be used to make the inks. In another family, the grandparents took part in the memory walk, which became an occasion to remember and talk about the lost twin. Both families included their children in the memory walks, and they helped to choose which materials were collected.

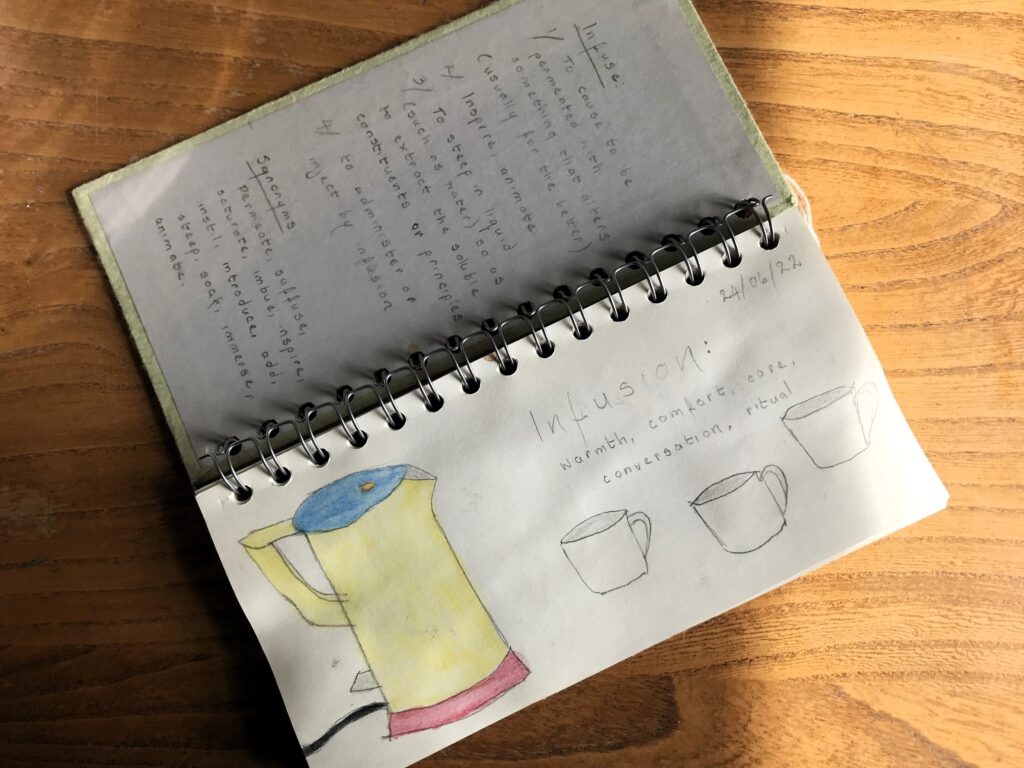

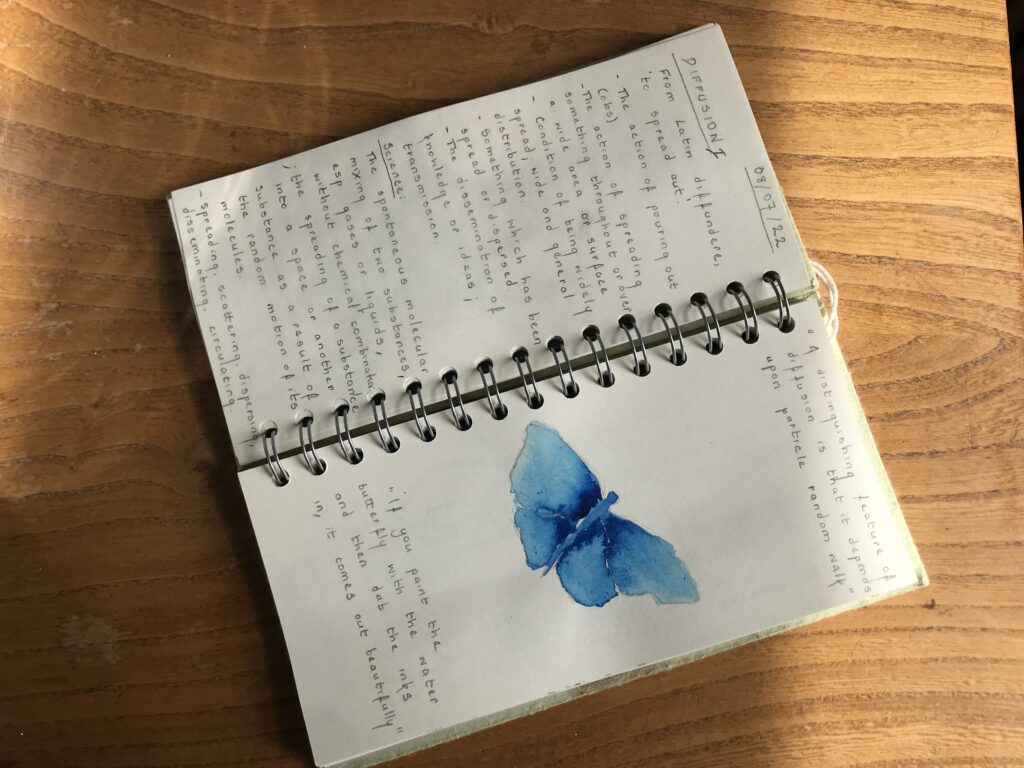

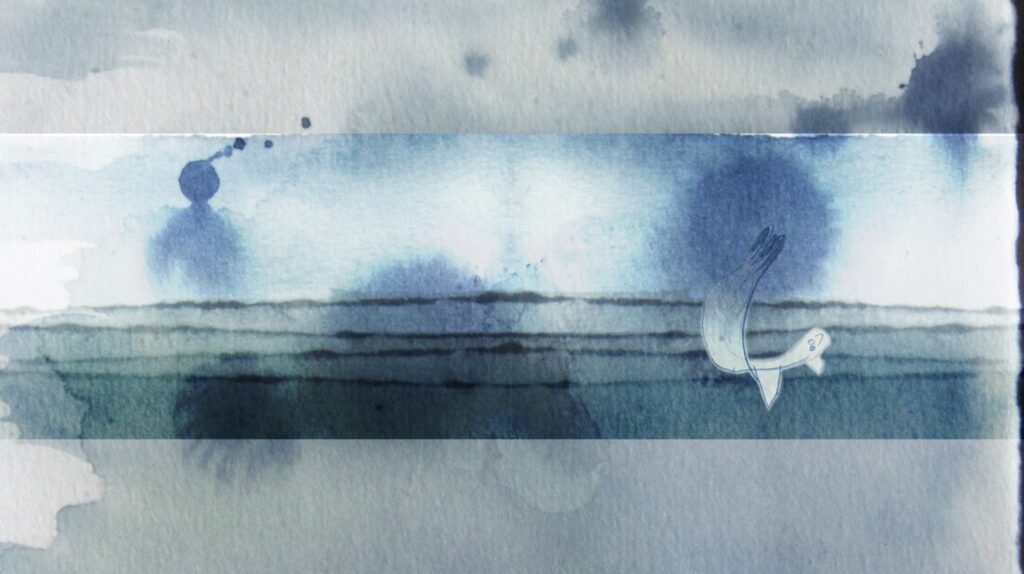

The sketchbooks Kate provided were used by the parents to record images and thoughts relating to the project. Each of the parents also gave a sketchbook to their children. As the project progressed, we received drawings from them, giving us a glimpse into the sibling perspective on this form of grief. On the memory walk, one co-twin sketched the surrounding hills using ‘ink’ from bilberries collected on the way, and Kate used this drawing for the title image of the film. Another co-twin declared at the end of the memory walk that she had seen a dolphin in the sea, and she drew this in her sketchbook. Kate animated the drawing to end the film.

For the parents, it was important to talk to their children about their lost siblings so that they remained a constant presence in the family. The memory walks extended the ways in which they were already creating memories with their children. One of the parents observed, ‘The memories are so few, and the focus is around the funeral. The project is giving us the prompts to create new memories.’

At the beginning of the project, the parents expressed a wish to help other parents by making the film. During the course of the project, they came to see the film as a document that they could also share with their children, either now or when they are older and want to know more about their siblings who have died. One parent described the film as a way of ‘safeguarding for the future’.

While the parents remained the central focus of the project, it became clear that their grief could not be separated from the effects of the loss on other family members. The parents chose to involve their children and their own parents in the project activities, and the film likewise sought to capture the contribution of different generations to its making.