This post forms part of a monthly series that documents the plants growing at The Angel of the North through a series of cyanotypes.

On a visit to Dundee, I discovered the work of cyanotype artist Alexander Hamilton. After studying the process at Edinburgh College of Art, Hamilton chose cyanotype as an art form that enabled him to explore and interpret nature. I came across his work in the form of a piece of public art, ‘Seed Chamber‘, which stands tall outside the Dundee Science Centre. Although the installation has faded in colour, it is still possible to appreciate the design of delicate seedheads that float up the panels, as if blown skyward by the wind. The tall glass sculpture was originally illuminated from within, to symbolise the importance of light in the life cycle of plants, and it also references the process of making the cyanotype, with the image exposed by placing the chemically treated paper in sunlight. I found a book dedicated to Hamilton’s work in the bookshop of the nearby Victoria and Albert Museum, and I bought it in order to learn more about this important practitioner of cyanotype.

In Search of the Blue Flower is named after one of Hamilton’s own projects, the title of which references the Celtic folk tradition of an elusive blue flower, symbol of the endless pursuit of something that lies always just beyond reach. In her ‘Introduction’ to the volume, Sara Stevenson highlights Hamilton’s making of the cyanotype not merely as a means of documenting a specimen, but as a complex interaction with the plant and its environment:

The plant is laid on the paper which will capture an image of its delicate complexity; at the same time, sap and colouring may leach into the paper and interact with the chemistry. The erratic sun in Scotland defines the image – a silhouette combining shadow with transparency, drifting round the edges, and even showing us inside the plant. The chemical reaction follows the light, and the atmosphere – dry or damp. This is not simply what we might see of the plant but a response to its nature. (p. 7)

Hamilton’s cyanotypes further emphasise the plant’s unique ecology by using fresh water drawn from a nearby natural source to develop the image. (The paper is immersed in water to wash away the chemicals, and the contact causes a chemical reaction which turns the paper deep blue.)

Hamilton contributes an essay to the book, recollecting his first extensive experimentation with cyanotype on the Scottish island of Stroma in 1973. This island in the Pentland Firth had been uninhabited since 1962, and Hamilton offered to conduct a survey of the plants on Stroma for the Edinburgh Botanic Garden. He stayed on the island for a year, and making cyanotypes was combined with the daily tasks of obtaining food, firewood, and fresh water. Hamilton writes of his survey of the plants on the island:

We divided a map of Stroma into quadrants and explored the island systematically, documenting plants and mosses. The island was small and flat, but it was extraordinarily varied and visually stunning. The plants on the island would vary from vast areas of blue flowers, with other patches showing swathes of red flowers. (p. 17)

The experience of being fully immersed in the landscape gave Hamilton a deep engagement with, and knowledge of, the plants’ environment and this laid the basis for all his subsequent work.

In 2007, Hamilton completed a residency at Brantwood, the former home of John Ruskin in the Lake District. He lived in Ruskin’s house, and the library and gardens were available to him every day. Hamilton focused on Ruskin’s eleven-year study Proserpina: Studies of Wayside Flowers (1875-1886); here, Ruskin shares Hamilton’s commitment to an understanding of the humble wayside plant. Ruskin was also profoundly drawn to the colour blue; like Hamilton, he saw an intense blue, such as that of the cyanotype, as a sign of the spirituality that can be generated by a close relationship to nature.

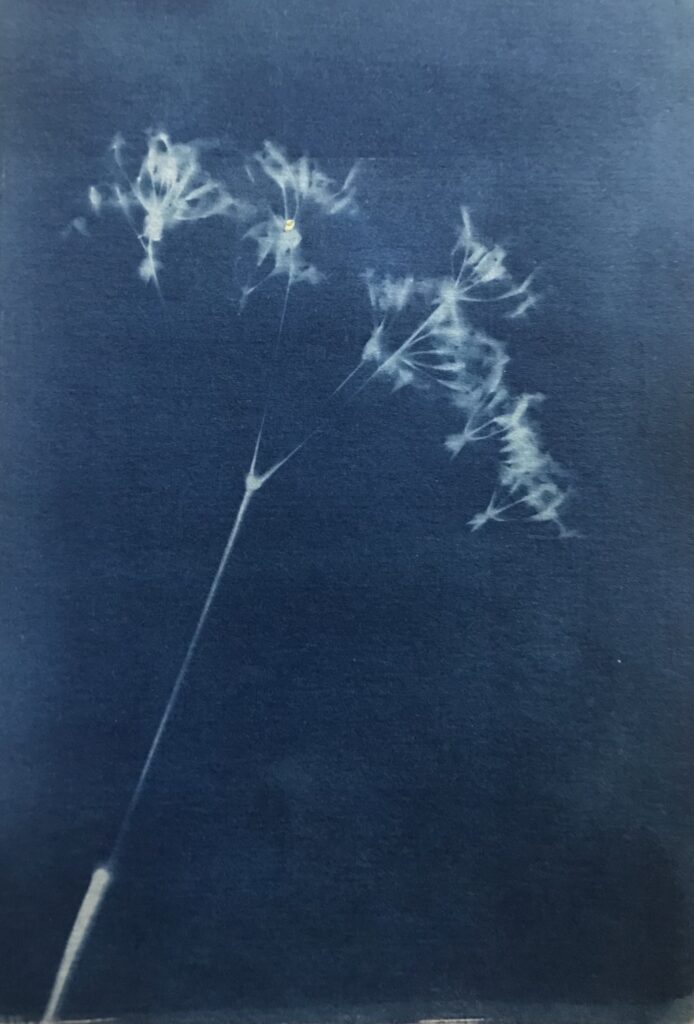

My own practice of developing cyanotypes at The Angel of the North also extends over the course of a year, capturing the plants that grow on the site across the different seasons. The uneven blue of my February cyanotypes witnesses the fluctuating light of the winter months, and the grasses leave their own residues of moisture and seeds on the paper, the traces of which are visible in the developed print. I used rainwater collected in my own garden to develop the image.

Unlike Hamilton, I did not approach the task of recording the plants at The Angel by systematically dividing the site into segments. My intention was not to produce a scientific survey, but rather to create an aesthetic record of the plants that grow on the memorial site. The creation of the cyanotypes represented a commitment to attend carefully to the flora and fauna of The Angel. As in January, the plants that I encountered in February were predominantly grasses and dried seedheads. The cyanotype celebrates the elegance and sculptural beauty of these commonplace and humble plants .

Hamilton’s tribute to the unattainable blue flower resonates with the broader context of this project. By leaving everyday ritual objects in the trees at The Angel of the North, visitors invest the site with spiritual significance. The process of making the cyanotype likewise transforms the ordinary into the intangible, and signals the quest for a connection with that which lies just beyond our senses.

References

Alexander Hamilton, ‘Stroma’, In Search of the Blue Flower: Alexander Hamilton and the Art of Cyanotype (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2022), pp. 17-19.

Sara Stevenson, ‘Introduction’, In Search of the Blue Flower: Alexander Hamilton and the Art of Cyanotype (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2022), p. 7.