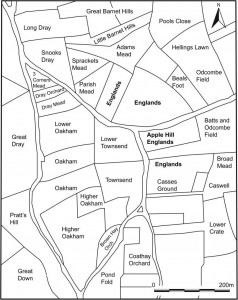

Every field in the land has a name and many of these names are recorded on Victorian Tithe Maps. Copies of these documents for Somerset are held by the Somerset Records Office. As part of the project we’ve been looking at the field names recorded on the Tithe Maps for Lufton and the surrounding parishes.

The names given to fields by people who worked them in the past often reflect something important about those pieces of land. They might tell us who owned the land (Ball’s Mead), they might describe the piece of land (Three Cornered Field), or they might tell us about the history of the piece of land. Chester would indicate a Roman site, Blacklands a site that might have been occupied intensely in the past. So far our work hasn’t turned up any of these names but there are an interesting group of fields over in Odcombe.

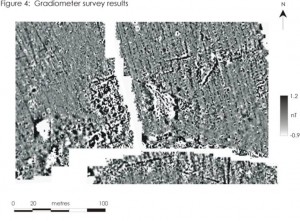

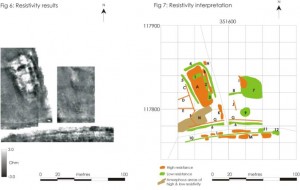

Just north of the village of Odcombe are a series of fields with ‘Englands’ names. This name is likely to derive from inland and this term is often associated with parts of early medieval estates that were under direct lordly control. Two recent pieces of archaeological fieldwork on fields with ‘Englands’ names in Charleton Horethorne and Sparkford have demonstrated that both of these sites were occupied in antiquity. The fields in Odcombe might also contain similar evidence.

A short article on this discovery will be published in the journal of the Medieval Settlement Research Group.