This blog was inspired by the simple question of ‘who was the first woman to gain a medical degree from the College of Medicine at Newcastle?’ In fact not so simple a question! The history of women’s medical education in Britain is a complex, fraught, and litigious one as women were forced to fight separately for access to medical education; for access to the medical profession; and for access to various closed branches of medicine. Rather than one ‘first woman’ there are therefore a group of several ‘first women’, as the College of Medicine at Newcastle expanded the award of its medical degrees firstly to women who had already received a medical education at non-degree awarding women’s medical colleges; then opening it’s medical programme to women, and finally admitting women to the various higher medical degrees and specialisms.

Thank you to research volunteer (and retired member of Library staff!) Alan Callender for this blog piece and for all of the hours of painstaking research behind it. Information was gathered using our collection of student registers and medical college class lists (Newcastle University Archive) together with information kindly given through family research.

Women’s access to the medical profession in the Nineteenth Century

By the mid-19th Century there were two significant barriers to British women becoming doctors – firstly access to a medical education, and secondly access to the registration process that enabled them to practice.

In 1834 when the ‘School of Medicine and Surgery at Newcastle’ was established, women were barred from a British medical education. However, until the middle of the century it was possible to gain a medical education abroad and return to practice in Britain without registration. The gradual opening of medical education to women in both Europe and the USA during this period increasingly made this route viable (for those with money to travel).

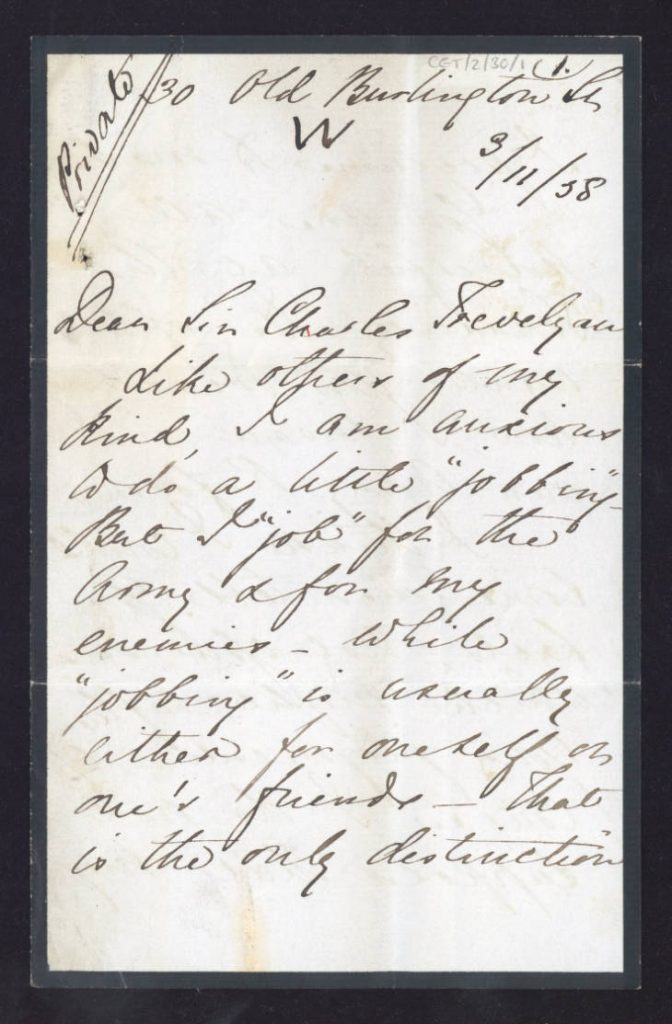

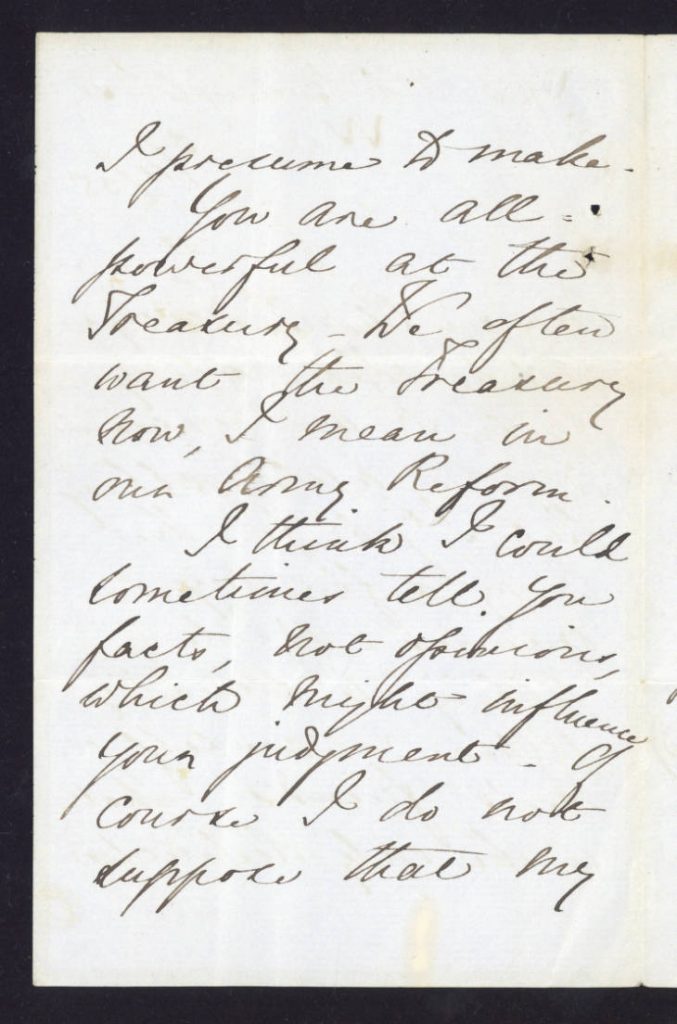

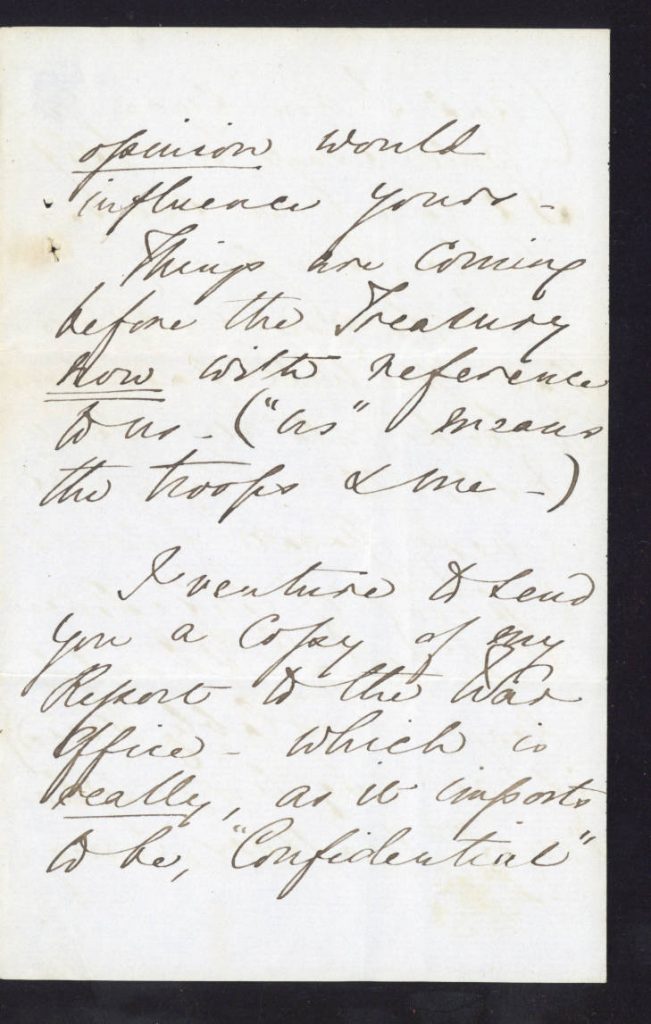

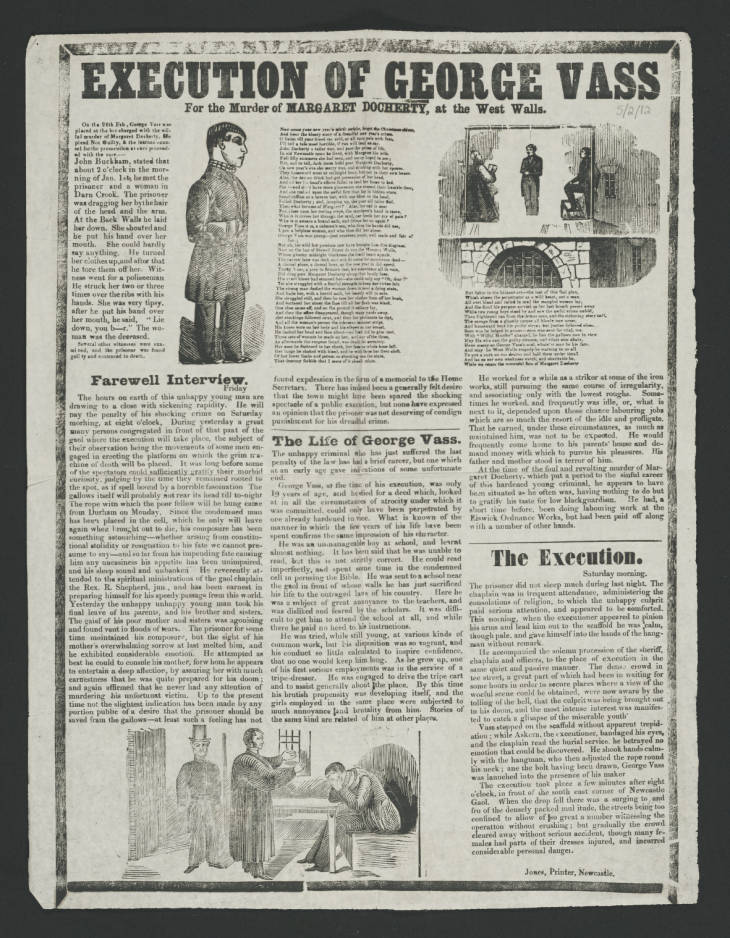

1858 Medical Act – The Creation of the Medical Register and a new barrier for women. This Act sought to professionalise medicine by formalising the educational requirements to practice medicine in Britain. However, by placing registration in the hands of those institutions who already prohibited women’s medical education, it acted as an insurmountable barrier to British women wishing to practice medicine. In 1865 Elizabeth Garrett Anderson (1836-1917) used a loophole to force the Society of Apothecaries to grant her registration. The society promptly closed this route and with it any options for women to legally practice medicine in Britain.

1869 the ‘Edinburgh Seven’ attempt to gain a medical education at a British University. In 1869 a group of seven women led by Sophia Jex-Blake (1840-1913) gained admittance to Edinburgh University and were allowed to attend some medical classes and take some medical examinations. As they progressed controversy grew as various sympathetic supporters (including much of the public press) pitted against opponents to the idea of women doctors. The fight was long and complex as Sophia Jex-Blake fought to access various routes, whilst the University responded each time by trying to close these routes. Eventually in 1873 the women lost their campaign. Despite having completed their medical degree courses the High Court ruled that Edinburgh University could not be forced to award medical degrees to women.

1874 The first British Medical College for Women is established. In 1874 Sophia Jex-Blake and Elizabeth Garrett Anderson founded the London School of Medicine for Women. Finally women had access to a medical education. However the College could not award degrees, and for students of the college the bar on medical registration still remained.

1877 A route to the registration of female doctors is established. In 1876, the ‘Enabling Act’ was passed which stated that the nineteen British medical examining bodies were permitted to accept women candidates but were not compelled to do so. In 1877, the King and Queen’s College of Physicians in Ireland became the first British medical qualification body to admit women for examination. In the same year, an agreement was reached with the Royal Free Hospital that allowed students at the London School of Medicine for Women to complete their clinical studies there.

The 1870s and 1880s and the growth of women’s medical schools. Once a route for both the education and registration of women had been established, three further colleges of medicine for women were established: 1886 Edinburgh School of Medicine for Women; 1888 Medical College for Women Edinburgh; 1890 Glasgow School of Medicine for Women (Queen Margaret College).

1880s and 1890s Women begin to access University education. Meanwhile, in 1867 the establishment of the North of England Council for Promoting Higher Education for Women had started the movement for opening university lectures to women, and by the 1880s and 1890s women were increasingly allowed to study at British universities. However, despite gaining admittance, and even passing university examinations, women were not allowed to be awarded degrees. This was significant for women wishing to study to medicine, as the refusal to award a degree meant an effective bar to the profession. In 1878 the University of London finally granted a supplementary charter to enable the admission of women to degree programmes, followed in 1895 by Durham University (the College of Medicine at Newcastle having by this time become a college of Durham University).

1890s and 1900s The growth of regional co-educational medical education. The opening of degrees to women in British universities did not necessarily mean that these women were allowed access to medical courses. In fact the University of London, the first University to grant women access to its degrees, did not admit women to its Medical Faculty for a further 39 years. Interestingly however, Durham started to accept women onto their medical degrees immediately. And in line with Durham various other northern universities also began to open their medical schools to women in the early 1900s. Equally significantly, most did not create a separate medical school for women as the early Scottish colleges had done. For women this was the start of a trend towards both co-educational medical training for men and women, and the growth of the role of regional universities in providing women with medical training.

Many other barriers were to present themselves over the next century, but we’ll stop there for now! And celebrate our pioneering medical graduates:

Our first female medical student 1892

The first female student – Edith Blanche Joel – appears on the student register at the College of Medicine. She appears again during the academic years of 1893/4 and 1894/5. However, at this time she would not have been permitted to graduate.

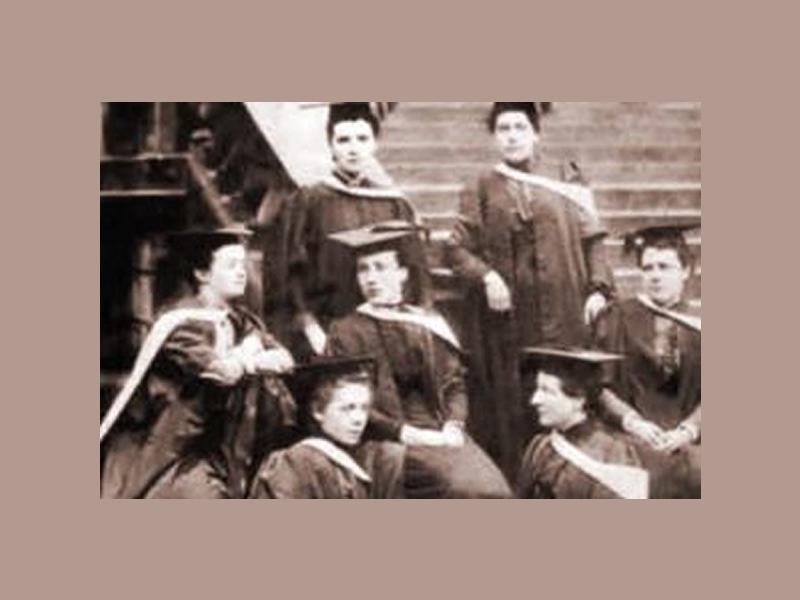

Our first women MBBS’s (Bachelor of Medicine, Bachelor of Surgery), 1898 and 1902

In 1896 three students from the London School of Medicine for Women, unable to graduate from this institution, registered at the College of Medicine at Newcastle to complete their medical degrees: Grace Harwood Stewart, Margaret Joyce, and Claudia Anita Prout. All three take their medical examinations and graduate in 1898. In 1896 Mary Evelyn De Russett also appears on the student register as a first year. In April 1902 she became the first female medical student to graduate who had undertaken all of her medical training at Newcastle.

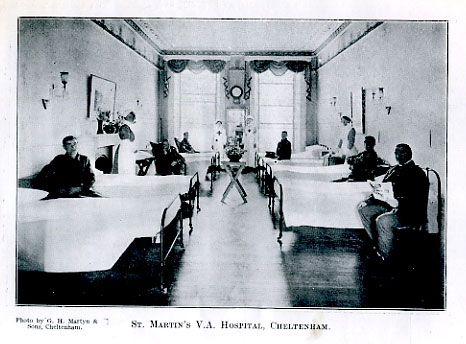

Grace Harwood Stewart (Billings) (1873 – 1957) was born at Portishead in Somerset, one of nine children to James and Louisa Stewart. Following her graduation from the Newcastle, she registered as a medical practitioner on 11 November 1898. Grace married Frederick Walter Billings, a builder, in 1899 and the same year established her medical practice at 3 Pittville Parade Cheltenham – the first woman to set up a medical practice in Gloucestershire. She went on to have a remarkable career and in addition to running her own practice was also a medical officer of the Cheltenham Infant Welfare Association and, a pioneer in family planning, she eventually set up the Cheltenham Municipal Women’s Welfare Clinic. During the First World War she was in charge of the St Martin’s V.A.D Hospital and was a locum anaesthetist at the Cheltenham General Hospital. Grace retired in 1936. Her daughter, Brenda, became a GP in Cheltenham and then School Medical Officer for Gloucestershire County Council. Her son, Stewart, had a distinguished naval career, becoming a Rear Admiral. He was awarded the CBE in 1953. She died on the 13 June 1957 at the Douro Nursing Home in Cheltenham aged 84. A great biography of Grace with some fabulous details about her amazing life can be seen here.

Margaret Joyce was born in Blackfordby, Burton-on-Trent in 1873. Following her graduation from Newcastle she registered as a Medical Practitioner on 18 November 1898. Margaret was in practice in Burton-on-Trent, and then became House Surgeon at the New Hospital for Women in London. She was subsequently in practice for many years in Liverpool and then Ashby-de-la-Zouch. Margaret died on 28 August 1966 at Syston in Leicestershire.

Claudia Anita Prout Rowse (Bell) was born in Hackney, London in 1873, one of five children. Following her graduation from Newcastle she registered as a medical practitioner on 15 November 1898. Claudia married Hubert Bell, a shipping agent in Chinkiang, China in 1910. The marriage register states that Claudia had been resident in China for 12 years at this point. Claudia died on 30 October 1950 at Reigate, Surrey.

Mary Evelyn De Russett (Howie) was born in Blackheath c.1872, although the family later moved the Tynemouth. Following her graduation from Newcastle, she registered as a medical practitioner on 9 May 1902. Mary married a doctor in 1902, John Coulson Howie, and together they ran a practice in Glasgow. After John’s death in 1912 the family moved to Newport. In 1920 she was appointed Maternity and Child Welfare Medical Officer for Durham County, a post which she held until her retirement. It should be noted that this post was open to her only because she was a widow, the Civil Service Marriage Bar prohibiting the employment of married women until it was abolished in 1946. Mary died in the Leazes Hospital in Newcastle on 7 September 1946.

Our first Women MDs (Doctor of Medicine), 1903 and 1906

An MD is a higher doctorate or research doctorate. In 1903 Selina Fitzherbert Fox, became the first woman to graduate with an MD from Newcastle. Selina had undertaken her initial training at the London School of Medicine for Women before transferring to Newcastle to complete her MBBS in 1899 and then proceeding to her MD. In 1906 Sophia Bangham Jackson became the first woman to gain her MD who had undertaken all of her medical training at the Newcastle College.

Selina Fitzherbert Fox was born in 1871. After her graduation from Newcastle she registered as a medical practitioner on 10 May 1899. Selina worked as an Assistant Medical Officer for the Zanana Bible and Medical Mission between 1900 and 1901 but returned to Britain because of ill health. She settled in Bermondsey and worked at the Church Missionary Society’s medical centre until it closed. As there was still the need for medical care for women and children in the area, Selina founded the Bermondsey Medical Mission in 1904 and was awarded an M.B.E for her work as its founder and director on 1 January 1938. Selina died at Bermondsey Medical Mission Hospital on 27 December 1958. A family blog about Selina and the campaign for a Blue Plaque to honour her can be seen here and here.

Sophia Bangham Jackson (Smith) was born in Finsbury Park in 1877. Following her graduation from Newcastle she registered as a medical practitioner on 12 November 1904. Sophie practiced in Thornton Heath, Chingford and then Selsden. She married Frederick B Smith in 1939 and died on 18 January 1952 at Selsden.

Our first women to be awarded a Bachelor of Hygiene, 1902 and 1909

In September 1902 Emeline Da Cunha, who had gained her Licence in Medical Surgery from Bombay University in 1894, became one of two ‘first women’ to be awarded a Bachelor of Hygiene from the College of Medicine at Newcastle. Joining her was Esther Molyneux Stuart who had undertaken her initial medical training at Edinburgh University. The first woman to be awarded a Bachelor of Hygiene who had completed all of her undergraduate training in Newcastle was Gertrude Ethel O’Brien who gained her MB in 1908 and subsequently her Bachelor of Hygiene and Diploma in Public Health in 1909.

Emeline Da Cunha was born in Panjim, India in 1873 and was awarded her initial Licence in Medicine and Surgery at Bombay University in 1894, funded by the Medical Women for India Fund. She later graduated from Newcastle with a B.Hy in 1902 and registered as a medical practitioner in England on 30 September 1901. From entries in the Medical Register it would appear that Emeline then returned to India to continue her career.

Esther Molyneux Stuart (Parkinson) was born in Liverpool on 19 January 1877. Esther registered as a medical practitioner on 4 August 1899 following her graduation from Edinburgh University, and in 1902 graduated from Newcastle with her B.Hy. She married Thomas Parkinson in 1903 and died on 19 September 1912 at Benton in Northumberland.

Following her graduation from Newcastle Gertrude Ethel O’Brien (Bartlett) registered as a medical practitioner on 15 August 1908. She married Robert Bartlett, and died on 19 February 1953 in Barnet.

Our first women to be awarded a Diploma in Public Health, 1908 and 1909

In April 1908 Lilian Mary Chesney (M.B. Ch.B. Edinburgh University 1899) became the first Newcastle female graduate to be awarded a Diploma in Public Health. One year later in 1909 Gertrude Ethel O’Brien became the first woman who had undertaken all of her medical training at Newcastle to receive this award.

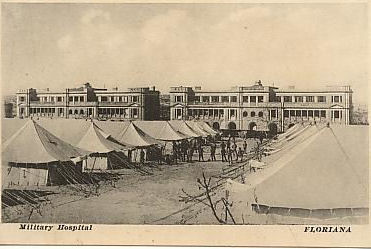

Lillian Mary Chesney was born in Harrow in 1869. Following her graduation from Newcastle she registered as a medical practitioner on 31 July 1899 and subsequently set up a practice in Harley Street. Later in life Lillian moved her practice to Sheffield and then to Palma de Majorca in Spain. During the First World War Lillian served as a doctor in the Kragujevac (Serbia) Unit 1914-1915 and the London (Russia and Serbia) Unit from 1916-1917. Thanks to the research of John Lines whose great aunt, Margaret Box, also served with the SWH, we have evidence that by October 1918 Dr Chesney appears to be running the hospital in Skopje (Serbia) for the SWH. Margaret refers to Dr Chesney in several of her wartime letters and calls her “our chief”. Lillian died on 20 December in Mallorca, Spain.

Our first women to be awarded a Master of Surgery, 1911 and 1923

In 1911 Charlotte Purnell was awarded a Master of Surgery, having undertaken her initial training at the London School of Medicine for Women before transferring to Newcastle. In 1904 Ruth Nicholson started her medical course at the College of Medicine at Newcastle, gaining her MBBS 1909, and BHy., D.P.H. in 1911. In 1923 she became the first woman to gain a Master of Surgery who had undertaken all of her initial medical training at Newcastle.

Charlotte Purnell was born in Dursley, Gloucestershire c1869. Following her graduation from Newcastle she registered as a medical practitioner on 13 April 1908. For most of her medical career Charlotte worked in Church Mission Society hospitals in Palestine and Transjordan. Her work was recognised by the award of the O.B.E in 1933. Charlotte died on 20 June 1944 in Amman in Transjordan.

Ruth Nicholson was born in Newcastle in 1885, one of six children. Following her graduation from Newcastle she registered as a medical practitioner on 16 September 1909. Before the First World War she practiced in Palestine, but returned to England at the start of the War, subsequently serving as Surgeon and Second in Command of the Royaumont Military Hospital in France. For this work she was awarded the Croix de Guerre and the Médaille d’Honneur des Épidémies by the French government. After the war she specialised in obstetrics and gynaecology as Clinical Lecturer and Gynaecological Surgeon at the University of Liverpool with consultant appointments at Liverpool hospitals. She was a founder member of the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists in 1929, being elevated to fellow of the College in 1931. Ruth died on 16 July 1963 in Exeter. A blog about Ruth’s fascinating life story can be seen here.

You may also be interested in an accompanying blog piece by Alan discussing the largely un-credited role of our female graduates in WWI: They also served…