This exhibition took place in the Marjorie Robinson Library Rooms, Newcastle University, 28th October 2016 – 15th January 2017. Click this link to see an online version of the exhibition.

Exhibition Open! “People don’t know about them…”

Ground Floor – Marjorie Robinson Library Rooms

28th October 2016 – 15th January 2017

“And then 1914, obviously the First World War is declared and she came back to England, and she’d been working as a surgeon. She offered her services to the War Office and the War Office accepted her and said yes and then she got her kit together and turned up at Victoria Station in London to join her group to go out to France to the military hospital out in France and the doctor in charge said I’m not having a woman. I’m not taking her.“

Rosemary Nicholson

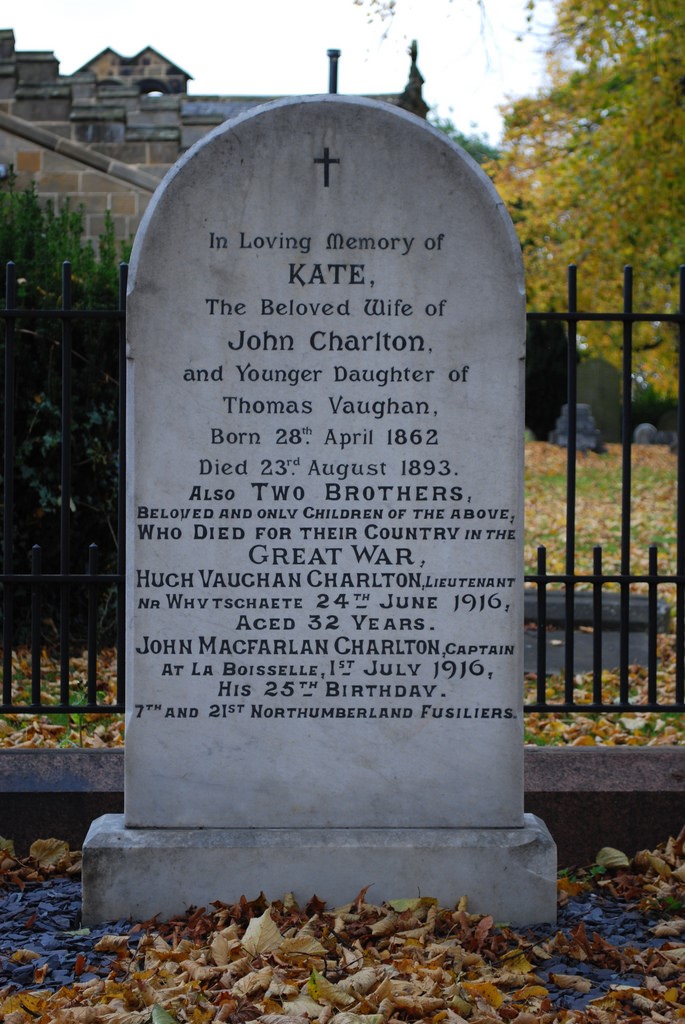

The Universities at War project is a volunteer project based in the Special Collections Department at the Philip Robinson Library. Its aim is to tell the stories of the staff and students of Newcastle University who fought in the First World War.

In 2015 Sam Wagner, an archaeology student in her final year of study at Newcastle University, joined the Universities at War project as part of her Career Development Module. For her final project, Sam chose to conduct an oral history interview, and that is where our story starts …

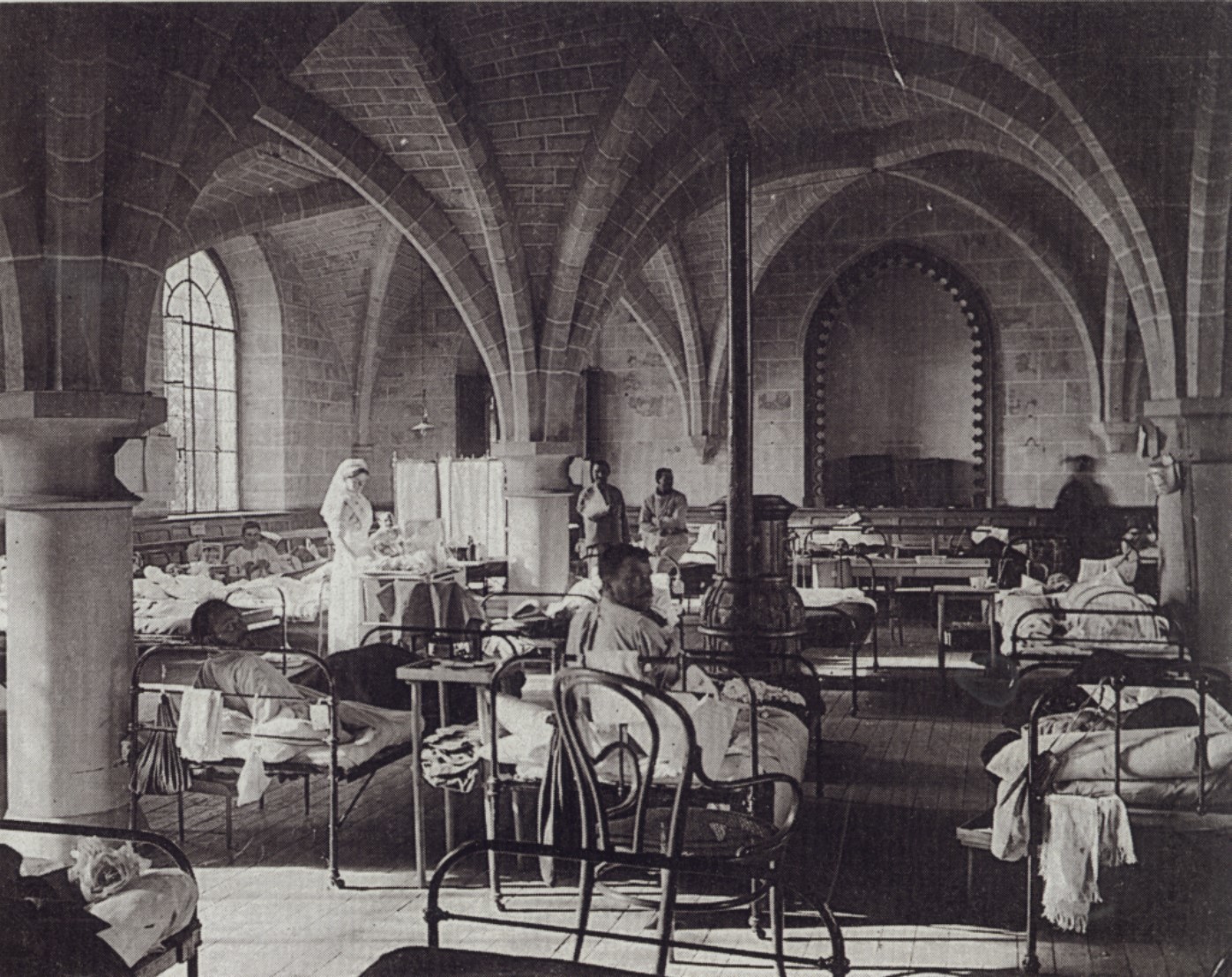

Rosemary Nicholson had previously contacted the Universities at War project to tell us about her husband’s aunt, Ruth Nicholson. Ruth was a Newcastle University medical graduate who worked under the direction of the French Red Cross throughout the First World War, as a surgeon in a military hospital in France.

A female medical graduate?

A military hospital staffed entirely by women?

And why the French Red Cross?

Sam’s exhibition is the result of her own historical research and interviews with Rosemary – capturing her memories of family stories about Ruth, as told through Ruth’s sister, Alison, who was still alive when Rosemary married into the family.

It is the fascinating story of an amazing woman, passed on by the women in her family who wanted her story to be told.

“ I felt she never got the credit she should have had, or the recognition she should have had, or Alison. People don’t know about them, I mean I write to everybody. I heard the programme on Women’s Hour about the women’s hospital in London and I rang right in to them saying, you know, What about Royaumont?! It was a matter of pride! ”

Rosemary Nicholson

All images in the exhibition have been kindly provided by the Nicholson family or other priviate owners, for the purposes of exhibition only.

The exhibition took place in the Marjorie Robinson Library Rooms, Newcastle University, 28th October 2016 – 15th January 2017.

An online version of this exhibition can be seen here.

A poster version of the exhibition can be seen here.