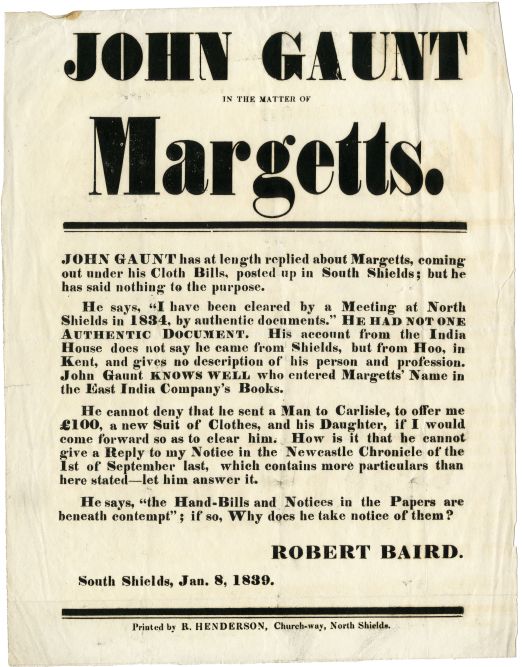

(Burnett Collection, Burnett 20)

The first collection of folk tales compiled by the brothers Jakob and Wilhelm Grimm was entitled Kinder-und Hausmärchen or Children’s and Household Tales. Published 200 years ago, on 20th December 1812, they were based on German folk tales, which were widely-known in oral tradition but had never been written down as a complete collection. The brothers’ aim was to gather the traditional folk tales of the common people together and for them to be accepted and read by the rising middle classes. However, they have been criticised for changing characters and meanings in order for the stories to appeal to an audience that valued hard work, patience and obedience. Kinder-und Hausmärchen was the second most popular book in Germany during the Twentieth Century, second only to the Bible.

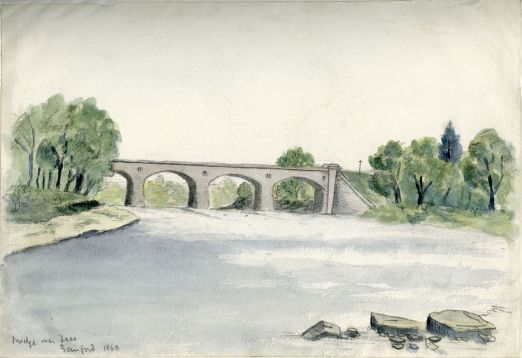

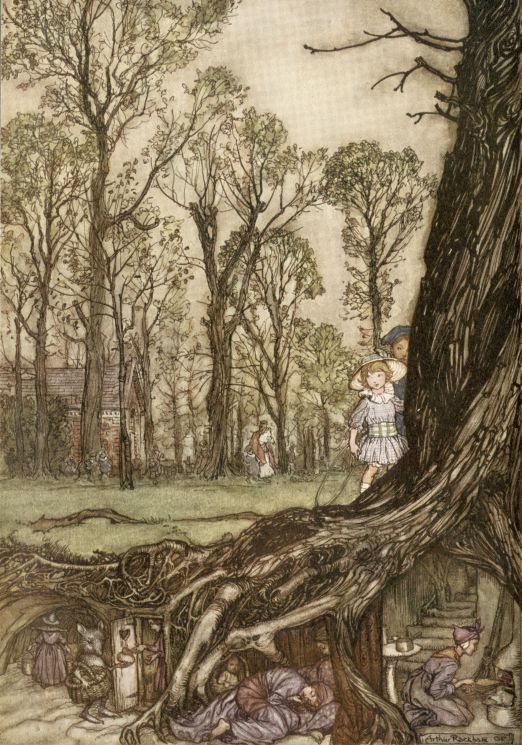

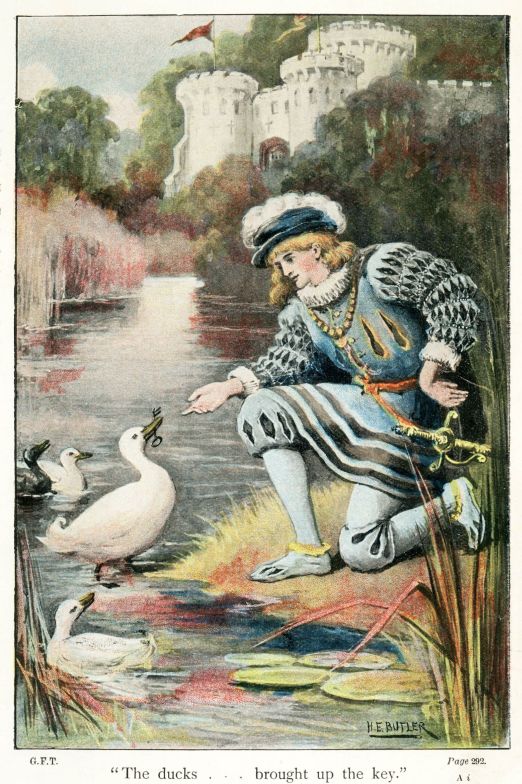

These images are from an early twentieth-century edition of the original tales. The illustrations were completed by Herbert Edward Butler (1861-1931). Butler trained at the Royal Academy, where he also exhibited in 1909. He and his wife, Sophia, lived in Polperro, Cornwall where he had a painting school. He specialised in large oil canvases, although after the First World War he began painting smaller watercolours and illustrating books.

Despite their misleading title, Grimms’ fairy tales were not originally intended as stories for children. It became increasingly popular for parents to read them to children, and the tales were revised in order to make them more morally acceptable, often removing references to sex and violence. The sanitised stories we assume Walt Disney was responsible for creating, were in fact products of the Grimm Brothers themselves who set about ‘cleaning-up’ the tales. Below are some of the most interesting changes that have taken place in the classic fairy stories since their first publication in 1812:

- The first-edition versions of Snow White and Hansel and Gretel featured the children’s birth-mothers as the villains, but this was later changed to the step-mothers, possibly to mitigate the violence of the stories.

- In Rapunzel, her relationship with the Prince was sexual as, after his evening visits, she noticed her clothes getting tighter; she was clearly pregnant. In this edition it is not included but their sexual relationship is still alluded to as the Prince discovers her living with their twins at the end of the story.

- In Snow White, the original tale ends with her step-mother, the wicked Queen being forced to put on red-hot iron shoes and dance until she fell down dead.

- In Cinderella the sisters cut off parts of their feet in order to make the slipper fit and trick the Prince into marrying them. In the end they get their eyes pecked out by pigeons.

The re-writing of fairy tales has been constant and continues today. In the late Nineteenth and early Twentieth Centuries the idea of Christian meritocracy was introduced into fairy stories, particularly in Britain and the US. God was portrayed as being on the side of the hero and religious paraphernalia was incorporated into illustrated editions of the fairy tales, such as bibles placed on bedside tables. In Nazi Germany, traditional folk tales were considered to be holy and sacred and were promoted by the government from 1933 onwards. The Nazis said that Kinder-und Hausmärchen was a book that every household should own and used the stories to create feelings of nationalism. They embraced the traditional folk ideals of purity, loyalty, maternal sacrifice and male courage and used the stories to socialise children. It can be argued that the close association of the Nazis with the traditional fairy tales was the cause of the accusations of anti-Semitism that plagued Walt Disney during his lifetime.

In February this year many of the national newspapers ran stories claiming that parents are no longer reading fairy tales to their children. Hansel and Gretel and Little Red Riding Hood were considered to be too scary; Snow White and the Seven Dwarves was seen as inappropriate because of the use of the term ‘dwarves’ and Goldilocks and the Three Bears for condoning stealing; and Cinderella apparently sent an outdated message about women being responsible for doing housework. Conversely, fairy tales have been popular for 200 years and the habit of reading them to children is well-established. The common themes of growing-up, familial struggles and fear of the unknown continue to make the stories relevant today. In addition they teach children important lessons about not trusting strangers, obeying their parents and loyalty. Will fairy tales die out? It’s doubtful, after all everyone loves a happy ending…

(Burnett (Mark) Collection, Burnett 20)