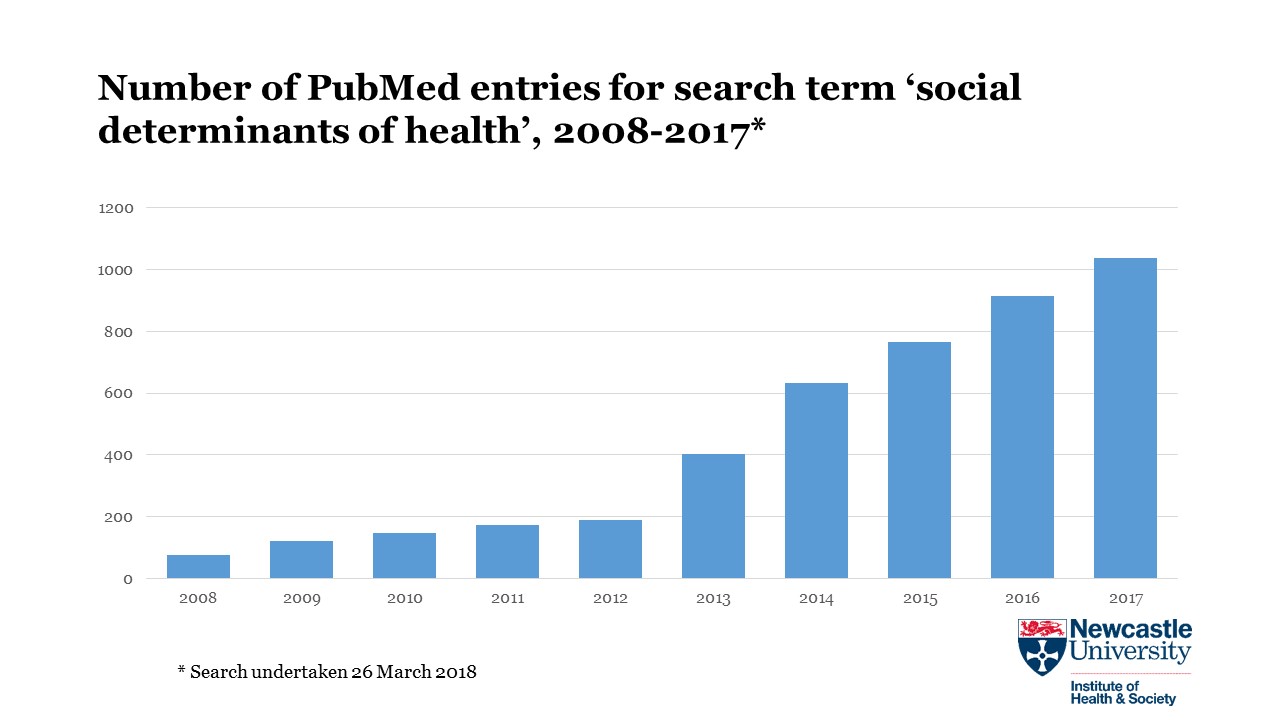

Like many colleagues, I have spent the past decade and a half mainly investigating the way in which macro-scale economic and social conditions and policies affect health by way of the unequal distribution of exposures, vulnerabilities and opportunities – the social determinants of health. The way in which authorities in the UK and elsewhere have responded to the coronavirus pandemic cries out for analysis from this perspective. Yet most colleagues’ silence has been deafening. Why?

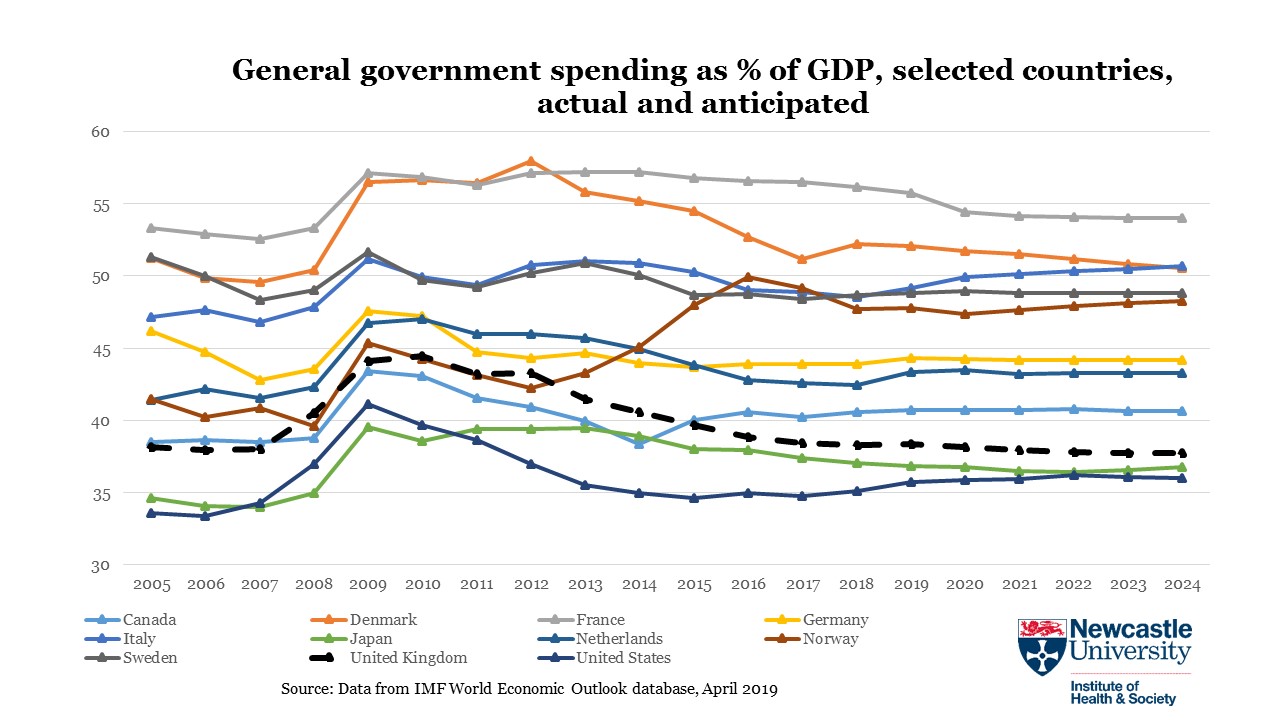

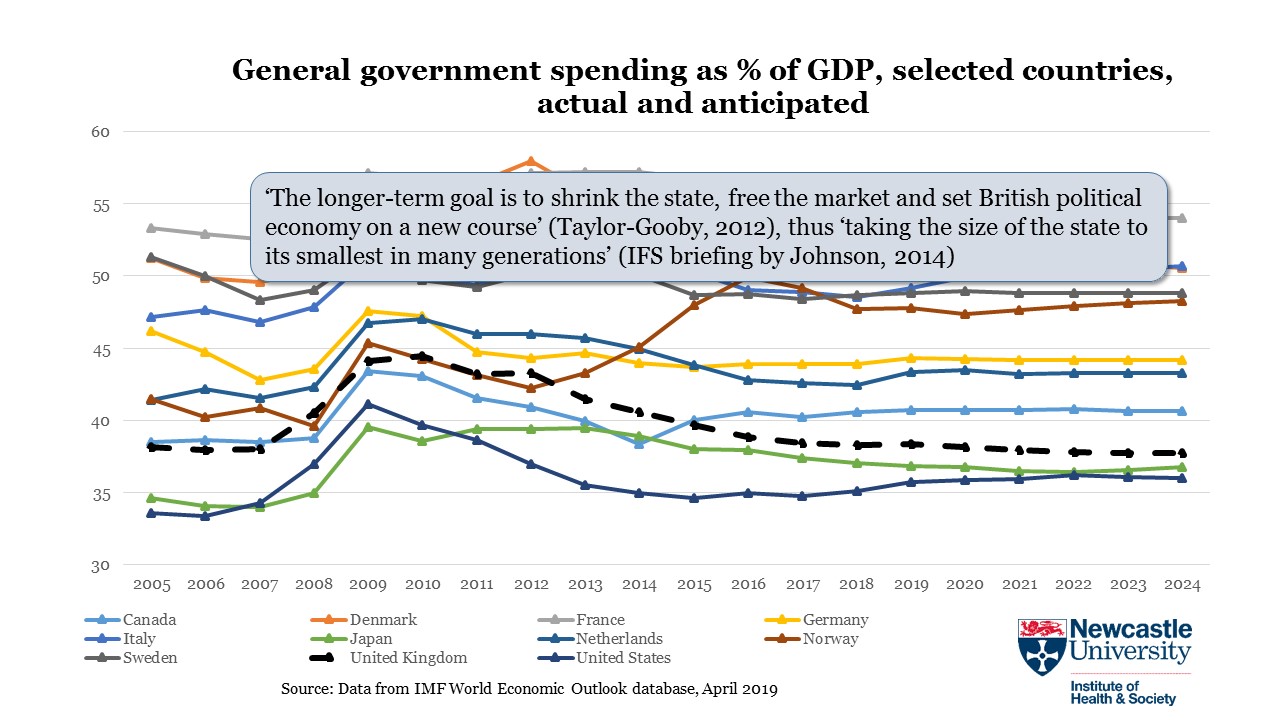

After all, to stay with the UK situation for the moment, the best post-pandemic outcome that can be anticipated is a prolonged recession, the consequences of which will be distributed unequally. Despite temporary assistance, many small businesses will not reopen, and many workers will exhaust temporary supports as their employers fail. After a decade of austerity local authorities are, to put it mildly, ill situated to provide necessary assistance. Such predictions are necessarily cast in general terms. Modelling the behaviour of economies is even more difficult than modelling epidemics of communicable disease, not least because external influences outside the control of even the best intentioned national policy-makers are more significant. Yet the population health community in the UK has been almost completely silent on these issues.

I suspect that part of the answer has to do with apprehensions about being identified with arguments for cautiously restarting the economy that mainly originate from the political right, like Gerard Lyons’ piece in The Telegraph or President Trump’s (in)famous statement that the cure cannot be worse than the disease – which, taken at face value without regard for its deranged originator, is unexceptionable. In the political arena, such an apprehension may be behind newly anointed Labour leader Sir Keir Starmer’s inexplicable and seemingly reflexive support for the Health Secretary’s threat on 5 April to ban all outdoor exercise if lockdown rules are not followed – a threat that probably has no basis in statute, and if carried out certainly could undermine the rule of law and citizens’ faith in it. There are sound arguments and important research questions here, about who will bear the financial costs of a prolonged lockdown and their health consequences, which have not been taken seriously enough by colleagues.

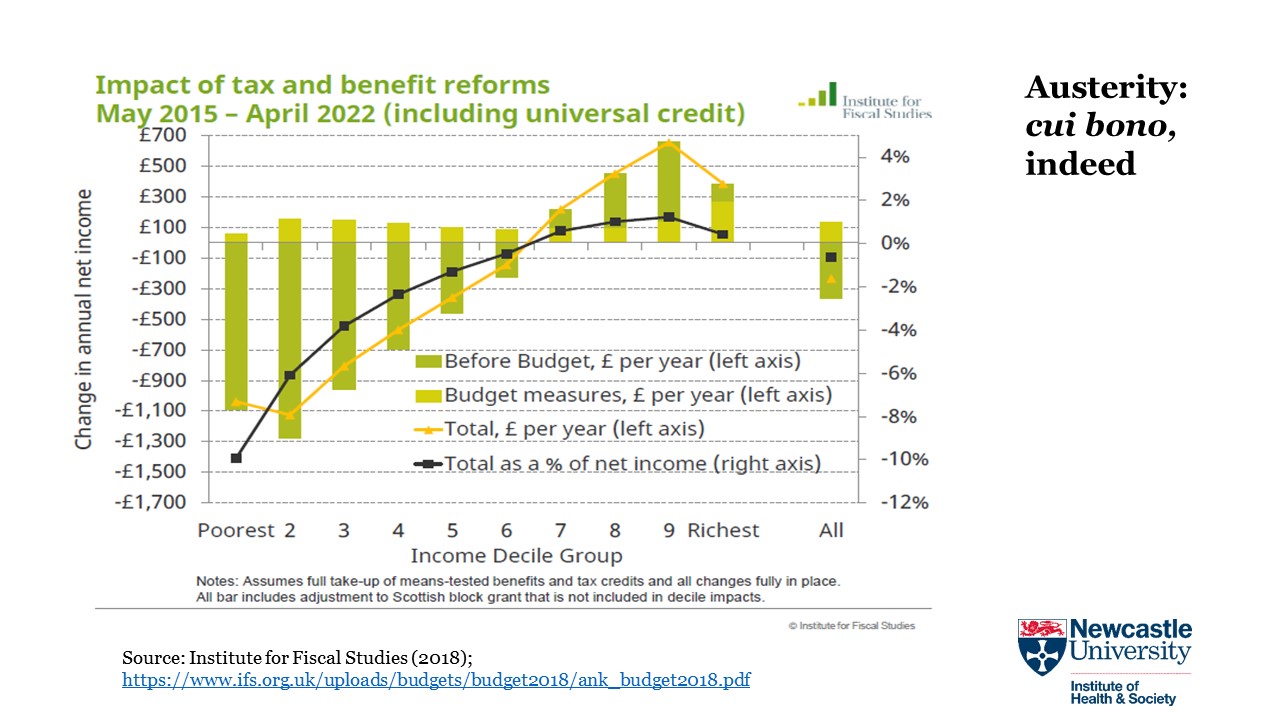

Quite apart from the material deprivation that can be anticipated as a consequence of potential economic collapse, there is the ‘loss of control over destiny’ about which Dame Margaret Whitehead and colleagues have convincingly written. Their important analysis operates on multiple scales, with the paradigmatic example of ‘pathways from traumatic social transition to poorer population health’ being the implosion of the former Soviet Union. An implosion of comparable severity, with oligarchs the primary beneficiaries, can be envisioned in the UK if both the pandemic and the retreat from lockdown are mismanaged. ‘Save lives at any cost’ is an emotionally appealing mantra, but no society anywhere, ever, has operationalised this at a population level. Destroying an economy itself has health consequences, the distribution of which will be highly unequal. An Institute for Fiscal Studies briefing shows that the lockdown will hit young workers, low-income workers and women the hardest. Impacts will also be spatially differentiated: Important research by Elena Magrini at the Centre for Cities identifies dramatic differences among cities in how many workers can adapt to work-from-home routines – or, alternatively, are vulnerable to job loss or disease exposure if they work in the essential sectors that are the unsung heroes of the pandemic. The credibility of all researchers concerned with health inequality will be defined in the coming months and years by how seriously we took these differences, and their implications for equity-oriented health, social, and economic policy – in the first instance, the design of exit strategies from the lockdown that is today in place. Those of us who did not take them seriously will no longer deserve an audience.

This post was updated on 6 April 2020.