“Thunder! Thunder! Thunder! Thunder! I was caught In the middle of a railroad track, I looked round and I knew there was no turning back”

From the song “Thunderstruck” by AC/DC

In June 2012 the city of Newcastle endured one of its greatest floods in history, infamously named the ‘Toon Monsoon’. It unleased 50mm of rainfall, the equivalent of one month’s rain falling within the span of two hours, and most of the flooding took place in the first 30 minutes. I remember it well, particularly people canoeing down Chillingham Road in the nearby neighbourhood of Heaton.

I watched most of the carnage ensue from my upper floor flat on the top of Shields Road in Byker. At the time I was safe, many were not. More than 500 homes were flooded in the city and 1200 properties in total were affected. The collective damages caused by the deluge were large and the impact of ‘Thunder Thursday’ was felt throughout the city. Now Newcastle is a demonstrator city for blue-green infrastructure focusing on practical solutions to reducing flood risk. Times have changed.

Flooding is a major problem for many cities, particularly in the wake of climate change. It is generally agreed that rainfall has and will increase as a result of the anthropogenic warming of the Earth’s atmosphere. What is less clear is how we prepare urban areas for flooding caused by intense heavy rainfall, especially if it occurs suddenly without warning. Cities are actually ideal test beds for new sustainable ways to mitigate flooding because they are usually densely populated, with mostly paved surfaces and have many buildings which are vulnerable to flooding.

Potential sustainable solutions to urban flooding have come under the banner of ‘blue-green infrastructure’. Infrastructure that is ‘green’ such as trees and other forms of vegetation, including gardens and parks, also serve as buffers or storage for rainwater. Infrastructure that is ‘blue’ stores water on the surface such as water butts, swales or ponds.

Evidence exists for why cities should adopt more blue-green features to prevent flooding, but rigorous testing of green infrastructure is greatly needed. The science could make cities better informed about how it actually works and make flood planning more effective. Adapting to climate change is likely not as simple as planting more trees in cities, although it could play a vital role if done strategically alongside other green or blue features and grey infrastructure, such as sewers and storm drains.

This is where the National Green Infrastructure Facility (NGIF) based in Newcastle University’s Urban Sciences Building at Newcastle Helix comes in. It is the only ‘living lab’ of its kind to test various kinds of green infrastructure and how they interact with surface water.

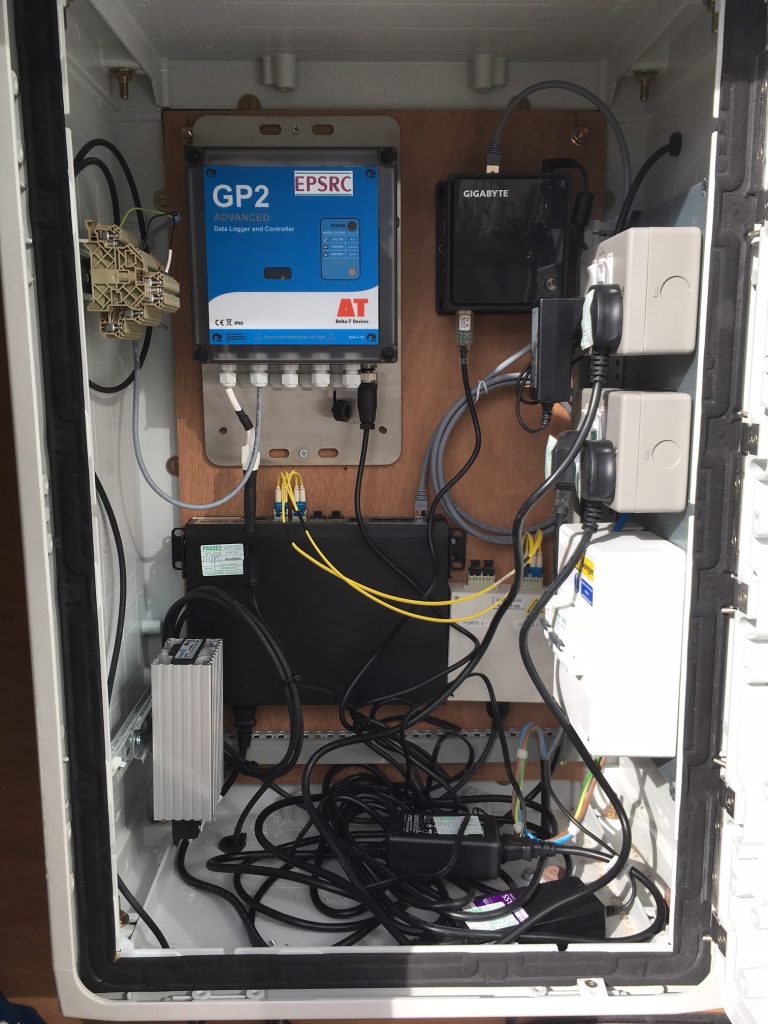

“A large part of what makes it a lab is actually what you can’t see as each feature is carefully instrumented with high precision equipment for measuring, for example, the ability of different types of soil to soak up and store water. The trees have special sensors installed in them which measure how much water they transfer back to the atmosphere”. Dr Ross Stirling, NGIF

There is no other facility like it in the UK and possibly the world, and is working closely with the water sector via Northumbrian Water Group to ensure findings are taken up by industry.

The Facility’s main remit is to:

- Provide proof of concept for green infrastructure solutions in real-world settings

- Understand how green infrastructure fares under extreme weather conditions

- Find out what knock-on benefits (if any) green infrastructure provides

- Answer whether green infrastructure does actually provide a sustainable solution to large storm events like the Toon Monsoon

There are a range of entering points in which scientists and engineers could be involved. Green infrastructure serves as a valuable carbon sink, and reduces air contaminants that plague cities like NOx and carbon monoxide. Research at NGIF could be useful to researchers interested in how green features could play a greater role in reducing air contaminants responsible for disease and mortality. Or for those wanting to improve energy efficiency of the built environment by cooling and insulating buildings. As green infrastructure also provides habitats to various animal and plant species, there are opportunities for increasing biodiversity as well.

An annual growth rate of 4% in the soil carbon stocks would halt the increase in CO2 concentration in the atmosphere related to human activities.

Seeing the National Green Infrastructure Facility for the first time it’s easy to overlook its lysimeters and simply mistaken them for large flower boxes, or its green infrastructure ensembles as only a row of trees on green lawns sunk into the floor. The cutting edge technical science stuff actually lies hidden within it.

The digital sensors in NGIF are connected to a city wide urban sensing network in Newcastle known as the Urban Observatory, and adds to its massive datasets on the urban environment from weather sensing to traffic noise and air quality. Similar to the rest of its vast network, data from NGIF will also be available in real-time for anyone to view online.

The challenges for flooding in cities are numerous, but if they are to adapt to extreme weather and an increasingly uncertain climate, studying how water interacts with green infrastructure in the urban environment could be essential to how we adapt to environmental change in the future. Because once the storm is here there’s no turning back!

Contact the National Green Infrastructure Facility for further info:

green.infrastructure@ncl.ac.uk

Further reading:

- ‘Putting green infrastructure to the test for urban catchments’, Water Industry Journal, September 2018

- Blue-green Cities project website: http://www.bluegreencities.ac.uk/

brett.cherry@newcastle.ac.uk