What I bring to the interview is respect. The person recognizes that you respect them because you’re listening. Because you’re listening, they feel good about talking to you. When someone tells me a thing that happened, what do I feel inside? I want to get the story out. It’s for the person who reads it to have the feeling… Studs Terkel

This week is Green Great Britain Week! And to help make a difference myself, colleagues and volunteers gave a public survey on what the people of Newcastle think about climate change, in collaboration with the Priestley International Centre for Climate at University of Leeds, University of York and University of Manchester.

According to the IPCC 1.5C special report released last week, carbon emissions must be urgently reduced even more than previously thought or the devastation caused by heating up the planet above the 1.5C target could cause it to veer in the direction of unlivable.

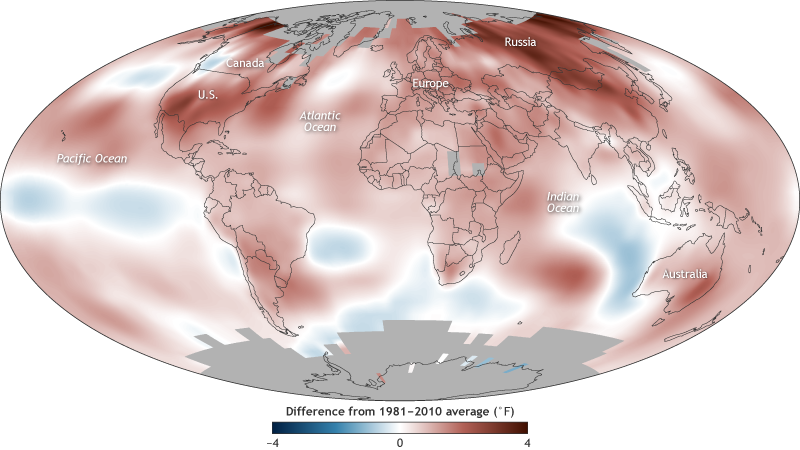

Climate change is far from easy to communicate let alone contemplate on a large scale. The 10 warmest years on record have occurred since 1998 and the four warmest years on record since 2014. Although the global temperature is rising rapidly, it isn’t uniform across the planet. While climate change impacts are certainly felt by people all over the world, how they experience them may vary.

The top of Northumberland Street near Haymarket Metro in Newcastle was a temporary lab to gather information about people’s opinions and experience (if any) of climate change and what they could do about it. We weren’t trying to get people hooked on Coca Cola, ask them to join a religion or tell them what to think, simply listen and maybe have a chat about climate. We were there to help give people a voice. Even if it was merely a snapshot in time – we did it.

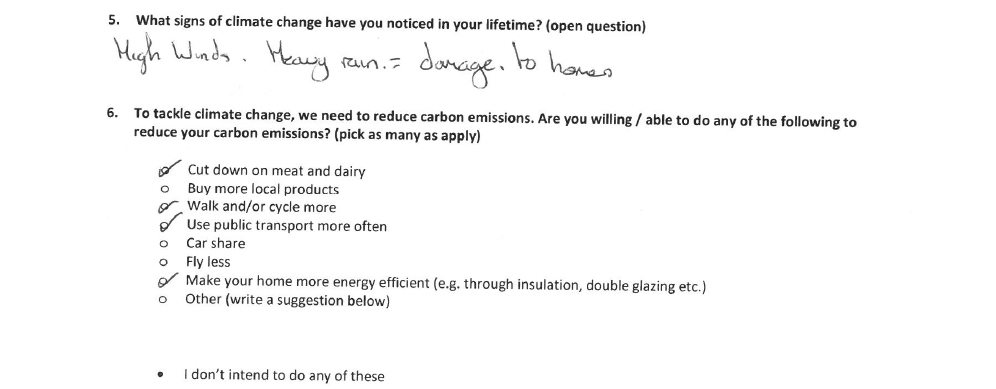

Within four hours we gathered 150+ completed surveys, and the main challenge was not getting people’s attention but to deal with groups of three or more. Everyone had something to say about how the climate is changing: young and old people, students, the homeless and shopkeepers.

Full results from the public survey given in Leeds, Manchester, York and Newcastle are now available online.

Often we forget that while anthropogenic climate change is something that is portrayed as controversial and that few people speak about it openly, everyone experiences the climate in some form or another. Similar to water or the air — climate is everywhere. It can’t be ignored, no matter how great or small the change may be.

Responses varied, many people spoke in groups and had a conversation amongst themselves about what they could really do about climate change, if anything. Many saw the options on the list as something they could, have done or are doing.

Others felt that it was something out of their hands and saw the actual impacts of climate change as still quite a few years off into the future, although many are not. I was impressed by a group of university students who said ‘it was their issue’ and that they needed to have their say.

Many expressed that the UK was lagging behind and not doing enough to inform people about the consequences of climate change, particularly government. Unless it was something persistently advertised it was not something on their radar or on the list of things that they should be concerned about as citizens.

While it is fair to say that many people ignored me when I asked them to take part in the survey, others thanked me. Our bright, friendly, multi-generational team of volunteers did well in getting people from many walks of life to do the survey. I also realised that a lot of people are often waiting near the Metro or a shop in standby until the next task of the day, and that having public conversation and dialogue about pressing environmental issues could actually take place far more often. It seems public conversation still has power.

As humans we have a stake in climate change, whether we accept the latest scientific evidence or not. My own pet theory is that people seem to know that something may not be quite right, that they may experience climate change impacts on a local, even personal level. I am far from the only one to take notice of this. It goes deep, perhaps to the root of who we are and why we exist. If existence precedes essence as some philosophers have put it, then climate — the elements — serves as the backdrop to the great drama of human life and even more drama shall it create.

I learned recently that 39% of the US population lives in coastal areas. That’s 123 million people in total. And how much is sea level expected to rise? Under the 1.5C scenario the sea level would be .1 metre lower compared to 2C. The chances of adapting are far more likely under 1.5C but if the planet reaches 2C or higher, get ready Nebraska you may just receive the population you’ve been waiting for, especially if you keep giving away free lots!

Will people cope? It’s a question that will be answered in time, but why wait? For extreme weather events existing infrastructure will likely not cope, placing many in a vulnerable position. Hurricane Michael left parts of the Florida panhandle in ruins. FEMA has warned that building back in the same way is simply not an option. If communities, government, developers and many others refuse or ignore this warning, future extreme events would have no problem in wiping them out as floods, hurricanes and droughts obey no one.

I mention these examples from the US because as the second largest emitter of carbon dioxide, methane and other greenhouse gases the repercussions of its actions will be felt at home as well as abroad. Yet we know that for people to act, unless it’s on their doorstep, it is unlikely to leave an impression that will drive them to action. Geoscientist Sue Kieffer calls climate change a ‘stealth disaster, one that develops over longer periods of time than natural disasters, often over decades or centuries’ (read my interview with her on p.52 of this publication).

An important point about climate change drawn from the Sustainable Development Goals is that it is linked to poverty. One of the main reasons why rapidly developing countries like China and India are contributing to our shrinking carbon budget is to get out of poverty. If we cannot resolve one, we will likely not resolve the other. Climate change makes the world poorer and worse off, but if responded to in an intelligent way could we do the opposite?

I’m listening.

brett.cherry@newcastle.ac.uk