If cities are to overcome the numerous challenges they are currently facing, including disasters, then it requires an array of sustainable techniques, methods and approaches for managing them. Cities are robust, often resilient but also fragile in the wake of perplexing environmental problems, such as climate change.

To clarify things a bit – hazards themselves are not disasters until they harm or eliminate life. A large-scale asteroid impact is most certainly a hazard but it will not be a disaster unless it harms life or damages the processes that support it. Earthquakes and flood hazards may be potentially disastrous but only in reference to the living things they are at risk of destroying.

The good news about disasters is that while they are not always preventable, it is possible to reduce their impacts through human means. In this geological epoch, climate change will persist regardless of human intervention, but its future impacts remain an open question – and humans have a strong role to play.

The people involved are as, if not more important, than the technical and scientific tools employed. Now is the time for cities to move forward in using the many available tools for improving cities, some of which are created and demonstrated through publicly-funded research.

For things to work in accordance with a plan or mission to adapt cities to environmental change, while also mitigating related factors such as air pollution, then it may be wise to have these ‘tools’ at hand for developing preparation and resilience measures.

Optimised spatial planning

‘Space is the place’ when it comes to managing urban environments. Defining space geographically, socially, economically and politically (amongst many other ways of defining space), makes a difference to how people live in cities. Disaster risk is connected to socioeconomic inequality and low-income households tend to be far more affected.

People will inhabit different kinds of urban spaces for a wide variety of reasons. Maybe they desire to live in a place that’s closer to their job, family or public facilities like hospitals. Or perhaps they live in an area because it is more affordable than what’s on offer closer to urban centres. Green space also plays an important role and urban areas with more green space are usually more desirable and healthier for city dwellers.

Computing, especially algorithms, make it possible to optimise how we plan cities spatially in a way that reduces risks to urban populations from environmental hazards, and understand any ‘trade-offs’ to help local authorities and communities plan effectively. This is possible by accounting for multiple different factors that affect cities and understand how, if at all, it is possible to balance them.

There is no sure way to eliminate risk completely, but it is possible to develop a ‘best case scenario’. Newcastle researchers have done this in their study on London, which accounted for heat waves and flooding, transport emissions, urban sprawl, brownfield, living and green spaces,

One of the ‘trade-offs’ they identified was moving development away from rivers and green spaces, avoiding flooding and sprawl, but developing in areas that have higher risk for heat waves.

For many Londoners, dealing with heat waves may not seem so bad, if not welcomed, but for older people the threat is large in terms of public health, increasing hospitalisations. The European Heat Wave of 2003 led to more than 70,000 deaths, many of them elderly, along with shortfalls in wheat harvest.

So if people become more exposed to heat waves, prioritising care of vulnerable populations may be wise in preventing hazards from turning into disasters. Reducing the size of homes was identified as an alternative option to more development in higher heat risk areas

Optimising urban planning using available computing technology seems to provide a smarter way forward in reworking if not radically transforming current urban planning and engineering. At the very least it deserves a serious look by planners, developers, communities and businesses.

Urban sensing, community engagement and citizen science

For spatial planning to work properly in averting the impacts of hazards, digital sensing in cities provides a powerful tool, especially in addressing environmental issues from a local to citywide scale, and for visualising data (see examples from Nick Holliman of eye popping urban data visualisations).

Digital sensors provide an important agency for communities and researchers working together to tackle an identified problem, such as air contamination, especially due to automobile traffic. Creating the appropriate technology can provide the substrate for community solutions.

The abundance of air pollutants such as NO2, NOx carbon monoxide, and others are literally decreasing the lifespans of people who inhabit cities.

It is especially problematic for schools where combustion powered cars queue and idle exposing young people to air pollution. Young people are in fact one of the most vulnerable populations to poor air quality, along with older people and those with health conditions, such as asthma, lung cancer and emphysema.

A community driven project working with Open Lab and the Urban Observatory – Sense My Street – works directly with the very people who live in the areas exposed to air pollution. Working with researchers, they use scientific grade equipment to detect air contaminants to measure the scale of the problem, which can feed into the policy process for managing air quality in cities.

Digital sensors are an important way for cities to investigate the problems that affect them on a local scale. They make possible new ways to monitor rainfall for example or even flood levels. Community monitoring can also play an important role here by engaging people with the techniques needed to convey environmental problems and develop evidence for change.

Digital twin

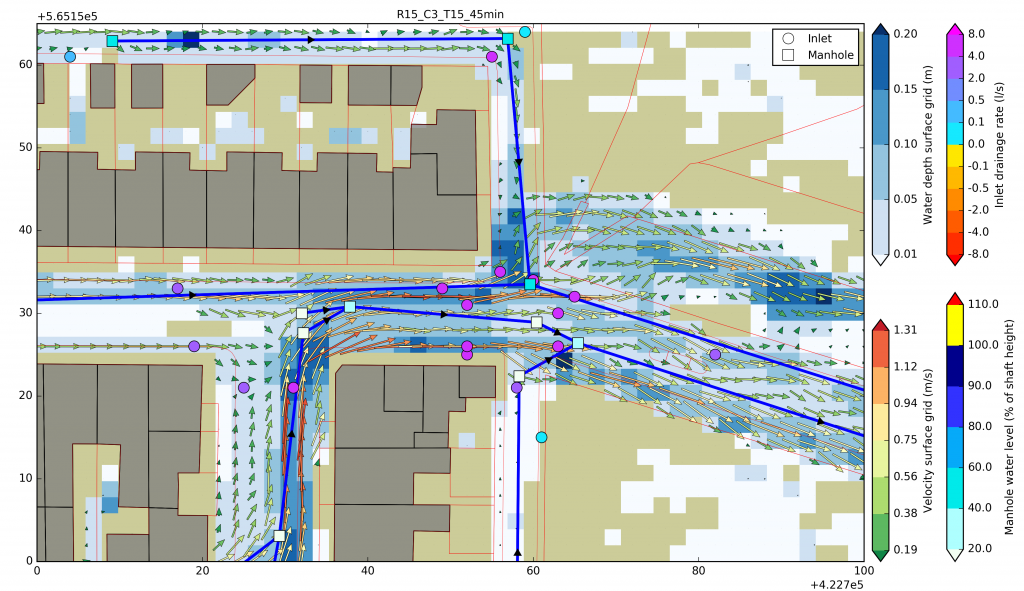

Using the tools above could ultimately feed into a digital replica of an entire city otherwise known as a ‘digital twin’. At the moment this exists in parts. Digital urban sensing provides the eyes and ears of the digital twin – it collects the information necessary to providing a real-time simulation or model of a city.

Hypothetically, a digital twin could revolutionise how cities adapt to environmental change. It would be possible to run a series of ‘what if’ scenarios in real-time to create more accurate and effective plans for cities, including climate adaptation.

Without sounding too dystopian, if you were going to plan for disaster a digital twin could realistically tell you what could be done in response and how to mitigate physical damage and loss of life.

These are just a few of likely many examples of how cities could prepare and plan for disasters, and at this time, my top three that I would say to someone passing in the street holding a sign reading ‘The End is Nigh’.

We already have some of the tools available for reducing if not averting disaster impacts in cities – let’s use them.

brett.cherry@newcastle.ac.uk