“The health of ecosystems on which we and all other species depend is deteriorating more rapidly than ever. We are eroding the very foundations of our economies, livelihoods, food security, health and quality of life worldwide,” Robert Watson, Chair of the IPBES

There is dire need to prevent the planet’s numerous flora and fauna from going extinct, including the many species that humans depend on for survival.

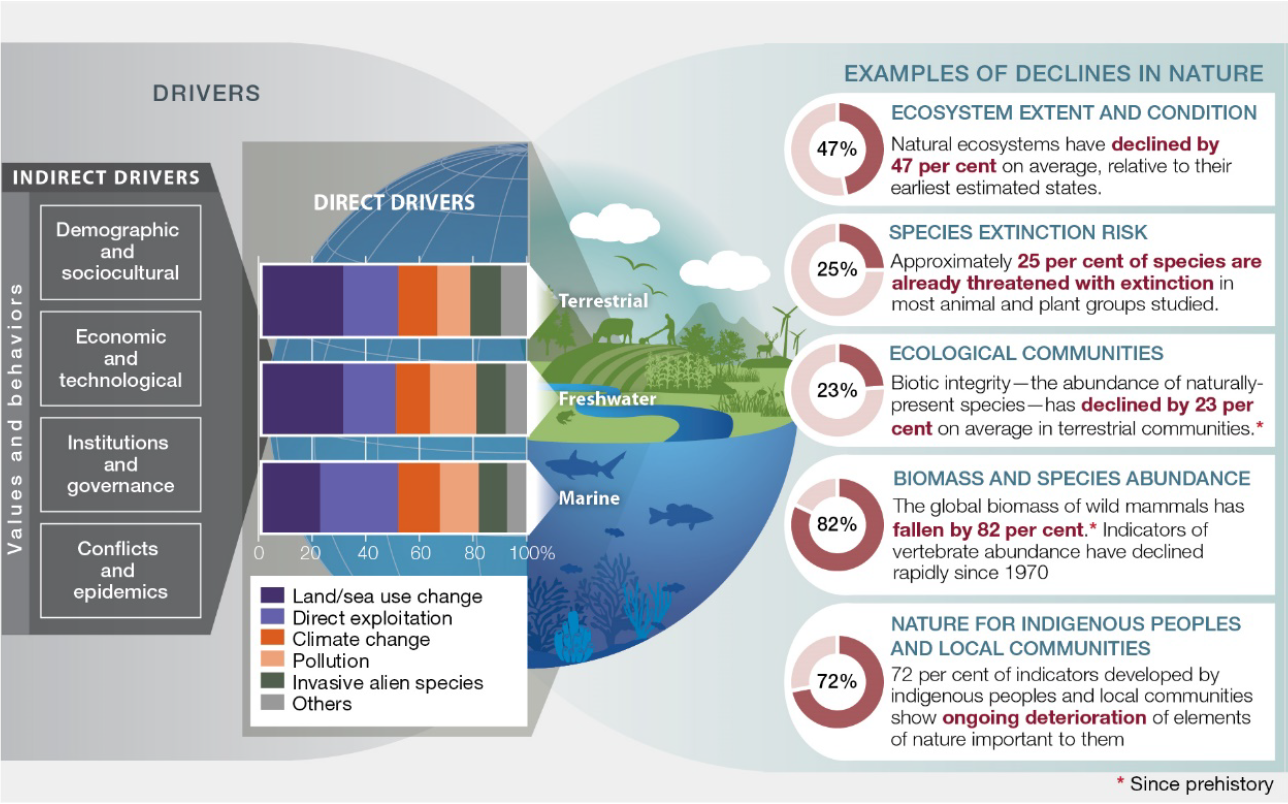

A recent report on the state of biodiversity from the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) makes clear that nothing less than transformation must happen for humans continues to live on this planet much longer.

Known long before the advent of science, the fate of the human species interconnects with its neighbouring species on the tree of life.

Species’ future existence affects and in many ways determines our own. As humans, the most dominant species on Earth, we fancy ourselves as makers of our own destiny, but time to conserve our biotic lifeline is running out.

Plants provide the air we breathe and the nutrients we consume for survival. They capture and store the solar energy that our bodies cannot absorb directly. Insects in turn pollinate that plants that we eat. Similarly, the animals of the land and the sea that we use as a food source, if they were to come under threat, would place our own species in quite a precarious position.

We need genes to protect against diseases for plants and animals. 70 per cent of drugs used for cancer are natural or are synthetic products inspired by nature.

The species we use freely with an open licence to access as many and however many as we like come from somewhere, and overusing them appears to be to our detriment.

Key Fact: By 2016, 559 of the 6,190 domesticated breeds of mammals used for food and agriculture (over 9 per cent) had become extinct and at least 1,000 more are threatened.

You can read about why this is important to the world’s food supply in a new article for The Conversation by Dr Phil McGowan and colleagues. More about solutions and what we can do about the future of biodiversity here.

Going forward ‘team humans’ needs to seriously question not only what it consumes, but how much it consumes.

Consumerism has always been a double-edged sword with economic growth coming at a cost to natural resources that was probably too great to begin with. Richer countries are encouraged to consume more and do so cheaply without batting an eye, while 800 million people don’t have enough to eat.

The Earth’s biological resources are vital to human life. Yet while the planet has the power to give us life, it also has the power to take it away. If this sounds similar to Gaia theory, which proposes the planet itself is one big complex living organism, you might not be too far off.

Whether used literally or metaphorically, Gaia, Terra, ‘spaceship Earth’, Aqua (most of its surface is water), or whatever you want to call it, it requires holistic solutions for addressing the ills we face and fast.

There is much to be taken from the IPBES report particularly the headline grabbling 1,000,000 species could go extinct in the next few decades and it doesn’t get any better.

For example, 300-400 million tons of heavy metals, solvents, toxic sludge and other wastes from industrial facilities are dumped annually into the world’s waters, and I take it that’s only the reported ones.

Agriculture is at the core of many problems to do with development of species habitats, leaving them with little if any place to go, literally pushing them to the edge. This does not somehow infer that farmers and agriculturalists are to blame, but rather should be part of the solution.

Agricultural demands are high and rising populations are going to demand more food. It’s how we do agriculture that is the take home message here, and in many cases it could be done a lot differently on a small and large scale.

Is there any good news about biodiversity or people’s relationship with the natural environment? Yes and there’s some great research which highlights them, with much more work to do. The role of people in managing landscapes and aquatic environments should never be underestimated. There are communities doing it well and it’s also helping to lift them out of poverty. All countries should take note.

Communities that live in or near the lush terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems that many strive to protect seem to hold some of the answers to protecting biodiversity and mitigating climate change.

In Nepal more than a third of the country’s forests are managed by a quarter of the country’s population. This is little less than astounding in its own right, but it gets better.

Recent research from Manchester, Newcastle and the University of Michigan, looked at the impacts of the country’s more than 18,000 community forest initiatives and came back with positive results, including reductions in deforestation and poverty. In Nepal a 37% relative reduction in deforestation and a 4.3% relative reduction in poverty that is attributable to community forest management.

Longer durations, over three years, of communities managing forests led to even further reductions in deforestation and poverty. The work also found that the deforestation reduction effect was higher in communities with lower levels of baseline poverty. For communities with higher levels of poverty additional support may be needed to achieve a similar effect. The reductions in deforestation and poverty are not uniform and decentralised forestry programmes clearly vary.

The results from this study published in Nature Sustainability are similar to what other studies have found on forest conservation and development in other countries, such as Mexico.

While an economic transformation is sorely needed that doesn’t use economic growth alone as an indicator of prosperity, economic development and biodiversity will continue to be at odds, but clearly local efforts play a major role in safeguarding the biosphere.

brett.cherry@newcastle.ac.uk