Dr Hazel Sheeky Bird

In the weird and worrying times that we are currently living in, it is good to be able to write about the positive things that are still taking place in the world of children’s literature. While locked down, I’ve been helping to put the finishing touches to three major areas of the Aidan and Nancy Chambers archive.

To give a bit of background: In 2016, Seven Stories was fortunate to acquire the entire archive of Aidan and Nancy Chambers. It is genuinely difficult to write an adequate summary of the immense contribution the Chambers have made to the whole field of children’s literature. (Anyone interested in finding out more about their work in general, and Turton and Chambers specifically, might like to look at my earlier blog on their work (https://blogs.ncl.ac.uk/vitalnorth/tag/turton-chambers/).

Being archivally minded, the Chambers amassed a colossal amount of material during professional careers that spanned over 50 years. This has proven to be exciting and daunting in equal measures, and meant that serious investment was needed to process the initial deposit and create a working catalogue. Fortunately, through a generous grant from the Archives Revealed scheme for an archivist-cataloguer, matched by funding from Newcastle University for a Research Associate, i.e. me, there have been two dedicated staff working on the archive for the last 18 months. Not only that, with management and input from Seven Stories’ Collection’s Manager, Kris McKie, and Senior Lecturer in Children’s Literature at Newcastle Uni, Dr Lucy Pearson, a significant amount of resources and expertise have been invested in the project.

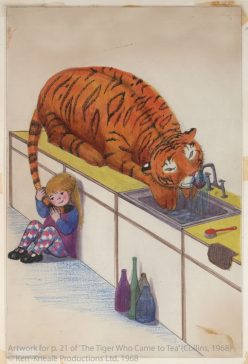

The Archives Revealed grant specified three distinct aspects of the overall archive to process in this first stage: Thimble Press, Signal: Approaches to Children’s Books (1970-2003), and Turton and Chambers. Aidan and Nancy Chambers set up publishing house Thimble Press in 1969, in the first instance to publish their own children’s literature journal, Signal. As editor, Nancy Chambers was responsible for publishing a wealth of articles on children’s books by contributors such as Elaine Moss, Peter Hollingdale, Peter Hunt, Philip Pullman, Margery Fisher and Eleanor Graham, to name only a few. Through Thimble Press, they also published seminal works of British children’s literature criticism such as Peter Hollingdale’s Ideology and the Children’s Book (1988) and Aidan Chambers’ own Tell Me: Children, Reading and Talk (1993). Many of these books are now instantly recognizable through the Chambers’ long collaboration with typographer, Michael Harvey. Harvey designed most Thimble Press covers and was responsible for the re-design of Signal in 1979, courtesy of Margaret Clark and John Ryder of the Bodley Head. Aidan Chambers set up Turton and Chambers (1989-1993) with bookseller David Turton to publish innovative works of children’s literature in translation.

The Chambers archive is huge. I could find grandiose ways to describe it, but the huge does the job. Aidan and Nancy Chambers had done a great job of organizing their vast papers over the years and initially deposited 126 large boxes with Seven Stories. A further accrual of boxes arrived in January 2020, and the Chambers continue to work on organizing the remainder of their papers at their home. When it first arrived, the papers were stored in a variety of boxes that the Chambers had amassed over the years. (You can see a very small fraction of the original boxes in the image below.)

Before any work on the papers could begin, Seven Stories’ conservator, Rosalind Bos, had to condition check the entire deposit. This is standard practice, but it was particularly important with the Chambers archive. Before coming to Seven Stories, the archive had moved around and was not always stored in ideal conditions. Mould was a particular worry: fortunately, only one box in the whole deposit was badly affected. It was the archivist cataloguer’s job to create the catalogue, but before he could do that, I had to weed the material.

Weeding is anathema to researchers, but necessary for archives and archivists. As a researcher, steeped in the assumption that everything in an archive is sacrosanct, it has been surprising that a big part of my job has been working out what should be kept and what could be set aside. The idea of weeding is disturbing. The Society of American Archivists offers us an alarming set of synonyms for the process: culling, purging, stripping. In practice, though, the process has been thoughtful, consistent and, most important for future researchers, useful. Today, the Signal archive is housed in organized and accessible archival boxes (you can see some of the archive below), ready for future researchers.

Think about the material relating to Signal: Approaches to Children’s Books. Nancy Chambers edited 100 issues of the journal over 33 years. For the majority of that time she corresponded with contributors through the post (the cost and reliability of the postal system is a frequent subject in her letters); keying (in preparation for typesetting) and proofs were sent to contributors (who may or may not have made changes to any or all of these stages). Nancy Chambers duly filed them on their return. On top of these versions, the archive also contained many photocopies of finished articles, most of which bore no annotation whatsoever, numerous pasted-up versions (i.e. copies of finished articles that had been cut up and pasted onto A4 paper), plus large amounts of camera ready copy for all issues. Nestled, and sometimes hidden, amongst this material was over 30 years’ worth of correspondence with major figures from the children’s literary world: think Robert Westall, Grace Hogarth, Robert Leeson, John Rowe Townsend, Sheila Ray, Jan Mark, Margaret Meek and Raymond Briggs for starters. Added to this, was the material that actually demonstrates Nancy Chambers’ practices as editor, and which reveals her collaboration with Margaret Clark on Signal following Clark’s retirement from the Bodley Head. Without weeding, anyone wanting to look at this rich body of material would have needed to set aside a significant about of their research time and budget to wade through many hundreds of pages of duplication, none of which revealed anything about Nancy Chambers’ editorial practices or the children’s literary world during this time.

At the outset, it was clear that we needed to agree on a set of guiding principles for weeding. Like all archives, Seven Stories already has a clear weeding policy, and this was our starting point. We also had to consider the nature of Signal as a publication: i.e. a journal as opposed to a literary work. We decided that we would keep limited draft material for articles published in Signal as, unlike literary works, there was likely to be limited interest in the writing process. Key exceptions were drafts, keying or proofs that had substantial annotation by the author or Nancy Chambers. Substantially annotated drafts of articles now considered seminal works of children’s literary criticism were also kept. I compared all drafts against the published versions and all correspondence was retained.

There were some exceptions: for example, the entire production file for Signal 1 was kept intact, even though annotated drafts were only marked up with typographic errors. I also could not identify any single issue file that reflected all production processes, so a representative amount of production material was retained and catalogued across the issues. This included, for example, handmade dummy issues, a sample index, Michael Harvey’s preparatory artwork, John Ryder’s production material for his ‘Leaves from a Designer’s Notebook’ inserts, etc. In terms of space, it simply was not possible to retain all production material for all 100 issues of Signal. The production material that we retained, however, documents not only the various processes that Nancy Chambers used over the years, but also the hands-on nature of her work as editor.

It literally took me weeks to weed the Signal material as I considered every item for its research value. In making these decisions, I was extremely fortunate to be able to turn to Nancy Chambers for aid. Weeding the Signal archive involved the removal of a significant amount of material, and it was vitally important that the final archive preserve and document Nancy’s editorial and publishing practices. Working collaboratively with Nancy Chambers meant that I fully understood, and could preserve, her working practices in the archive.

Having spent the last few weeks before the lockdown actually doing some personal research on Signal, I know that we have created an archive that is comprehensive and accessible. It has been a pleasure to read Nancy Chambers words, to ‘hear’ her voice, and to see her hand everywhere in the archive. At the time of writing, the launch of the final catalogue has been slightly delayed due to the lockdown. However, I look forward to seeing the many ways that future researchers use this unique archive.

Thanks for the article. As a model of transparency and lucidity it should be compulsory reading for all academics, especially those currently working on the virus.

I am a retired teacher of English who was a student and friend of Aidan when he taught at Westcliff High School for Boys. Please pass on my best wishes and regards.

Thanks for your comment Martin, I will ask Hazel to pass on your best wishes.