The Children’s Literature Unit Graduate Group (CLUGG) holds weekly 2-hour meetings where members pick a relevant theme to discuss together, allowing us as researchers to broaden our academic interests, learn from one other and engage more widely with the Children’s Literature academic community. By posting about our previous sessions, we hope to give you an idea of some of the research interests of CLUGG members, as well as the work that they are currently undertaking.

In this blog post, MLitt Student Enya-Marie Clay looks back on the first few CLUGG sessions of Semester 2. Further posts about CLUGG sessions will feature on the blog in the future, as and when members can contribute, so please bookmark the blog if you’re interested in future updates relevant to all things Children’s Literature at Newcastle University.

Session 1: 30th January 2019

In this session we discussed extracts from Peter Hollindale’s Signs of Childness in Children’s Literature (1997), specifically chapters 1 and 5: ‘The Uniqueness of Children’s Literature’ and ‘Signs of Childness: A Summary and Critical Approach’.

This prompted discussions surrounding key critical questions of the field such as:

- What is a child?

- What is children’s literature?

- What is the relationship between the intended reader and the producers of children’s literature?

We also discussed how Hollindale’s work sits within the broader landscape of scholarship by thinking about how it compares with the prominence of Jaqueline Rose’s work. This led to comparisons with non-British theorists within children’s literature, such as Perry Nodelman, and an exploration of how different social and geographical contexts affect the prominence of different works. In doing this, we also discussed which texts stand out as seminal reading and how these texts connect with the development of children’s literature as a discipline.

We ended the session by planning Semester 2 CLUGG meetings with the view to increasing the variety of activities and interests, such as student presentations and primary texts, and to move towards more student-led sessions now that the academic year is more established.

Session 2: 6th February 2019

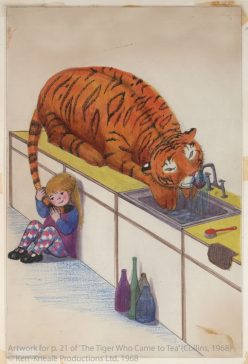

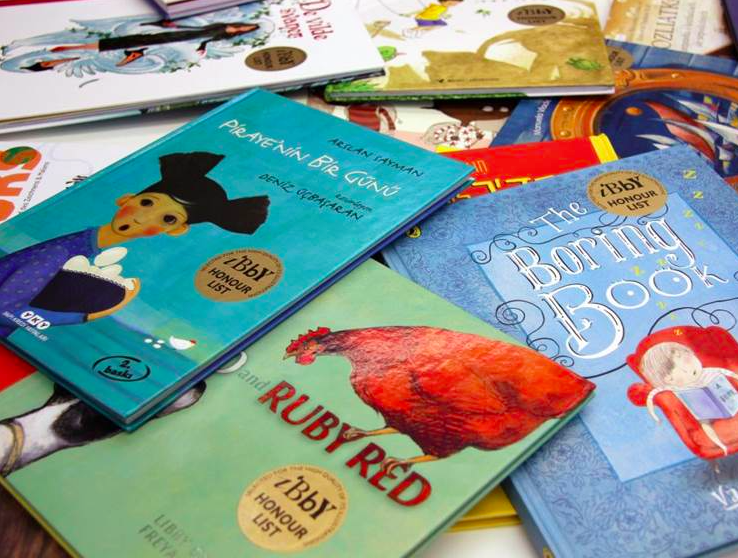

In this session we welcomed Rachel Pattinson, the Vital North Partnership Manager, who kindly brought along books from the IBBY UK Selection of Outstanding Books for Young People with Disabilities (2017) from Seven Stories.

We spent the session exploring the books and discussing their features. We were all struck by the importance of communal reading as a theme across the books, with many encouraging collaborative reading between the reader and child, such as Morgh-e Sork-e Pa Kootah (The Little Red Hen), which Rachel and Helen read together using the step-by-step guide to unfold the tactile story.

With the collection featuring books in over 40 languages from a variety of countries, we also had the opportunity to discuss how the books reflected their cultures of origin and how this compares with our understanding of children’s literature as British scholars. Yasuhiro Hunimori’s Ren-chan hajimete no mitori: Obaachan no shi to mukiau (Good-bye great grand-ma: A young girl’s first encounter with end-of-life care-giving), an incredibly moving photographic picture book with realistic photos of death, is a good of example of this, as we considered such stark images to be unusual in British children’s literature. This prompted conversation around how representations of trauma in children’s literature vary greatly across cultures and how this can reflect distinct attitudes to children and childhood.

The collection also features portrayals of disability (category 3), a notable example being a graphic novel titled El Deafo (2014) by Cece Bell. It was interesting how this novel transformed the bullying taunt ‘deafo’ into a superhero persona (hence the novel’s title), and thus showed a young protagonist celebrating their own disability. We discussed the novel’s use of speech bubbles, in which the text fades or disappears entirely to reflect the protagonist’s hearing loss, and how these effectively communicated the main character’s disability in a way that was accessible to readers who may not have experienced hearing impairment.

More details about the collection can be found on the IBBY website.

Session 3: 13th February 2019

This week’s session centred around an article provided by doctoral candidate Rebecca Jane titled ‘“Away with dark shadders!” Juvenile Detection Versus Juvenile Crime in The Boy Detective; or, The Crimes of London. A Romance of Modern Times’ written by Lucy Andrew. We used the article to discuss ideas surrounding penny dreadfuls, such as their use in juvenile court cases as Andrew discusses and how their depiction of violence differed in comparison to other periodicals of the time, such as The Boy’s Own Paper.

This led to discussions on ideas from Michel Foucault’s Discipline and Punish, such as how lurid descriptions and publicisation of a trial or a punishment can serve as a way of making the public an agent of control. We discussed this in the context of how violence was written about in the 19th century and then thought about how a degree of ‘acceptable’ criminality in the upholding of justice seemed to be a trope of the detective genre more generally.

We then discussed Andrew’s take on class and power tensions in The Boy Detective and explored the idea that penny dreadfuls could be a way of upholding conservatism through subversion; in other words, they can act as an abstract platform to explore ideas of criminality which exhausts the desire for this exploration in real life.

The latter part of the session then looked at ideas about radicalism in children’s literature and how different parenting styles globally can affect childhood experiences and the way that we ultimately come to research children’s literature. This led us to talk about attachment theory, the sacralisation of the mother/child relationship and how children’s literature traditionally reinforces this, and the adult fear of the loss of control over children as they mature. Through considering this, we recognised how our understanding of a text’s intended reader is socially constructed depending on context and how this must be considered when discussing texts.

Photo Credit: Rachel Pattinson, Vital North Partnership Manager, @rachelalmost. Texts from the IBBY Selection of Outstanding Books for Young People with Disabilities.