Workshopping the Poetry and Diaries of William and Dorothy Wordsworth

Hannah Piercy, doctoral candidate at Durham University, is part of a team of PhD students who recently set out to create sound pieces that bring William Wordsworth’s poetry to life and highlight the pivotal role Dorothy played in her brother’s creative process. The project – a collaboration between the Wordsworth Trust and the Northern Bridge Doctoral Training Partnership – included a workshop with students from Keswick School at the Wordsworth Museum in Grasmere. Here, Hannah reports on the team’s work with the students and shares some of the poetry they composed in response to the Wordsworths’ writings.

The 5th of June 2017 was not so much ‘a fine showery morning’, as Dorothy Wordsworth says of the 5th of June 1802 in her diaries; it was one of those days when being outside for a few minutes can get you soaked to the bone – a typical rainy day in the Lake District, some might say. I grew up in the Lakes, not so many miles away from Dove Cottage in Grasmere, where the Wordsworths lived for almost nine years. And as a secondary school pupil, I attended Keswick School, so there was a special pleasure for me in meeting some of the current year ten students of Keswick School to workshop some creative and critical ideas about the poetry, diaries, and lives, of William and Dorothy Wordsworth.

To create a manageable plan for workshopping William and Dorothy’s work in less than five hours, we had decided on a short list of poems and diary entries to discuss and record with the students during the day. We ran four sessions, discussing and trying out creative exercises based upon one of William’s poems and one of Dorothy’s diary entries in each session. Some of the texts we chose, like I Wandered Lonely as a Cloud, were obvious choices, but some, like The Tables Turned, perhaps seem less obvious. We chose to pair The Tables Turned with Dorothy’s diary entry for 15th April 1798, written before the Wordsworths moved to Grasmere, when they were living in Alfoxden house, Somerset. The Tables Turned implores its addressee to ‘quit your books’ and ‘Come forth into the light of things, / Let Nature be your teacher’, while Dorothy’s diary discusses how ‘Nature was very successfully striving to make beautiful what art had deformed – ruins, hermitages etc’, and notes that ‘Happily we cannot shape the huge hills, or carve out the valleys according to our fancy.’

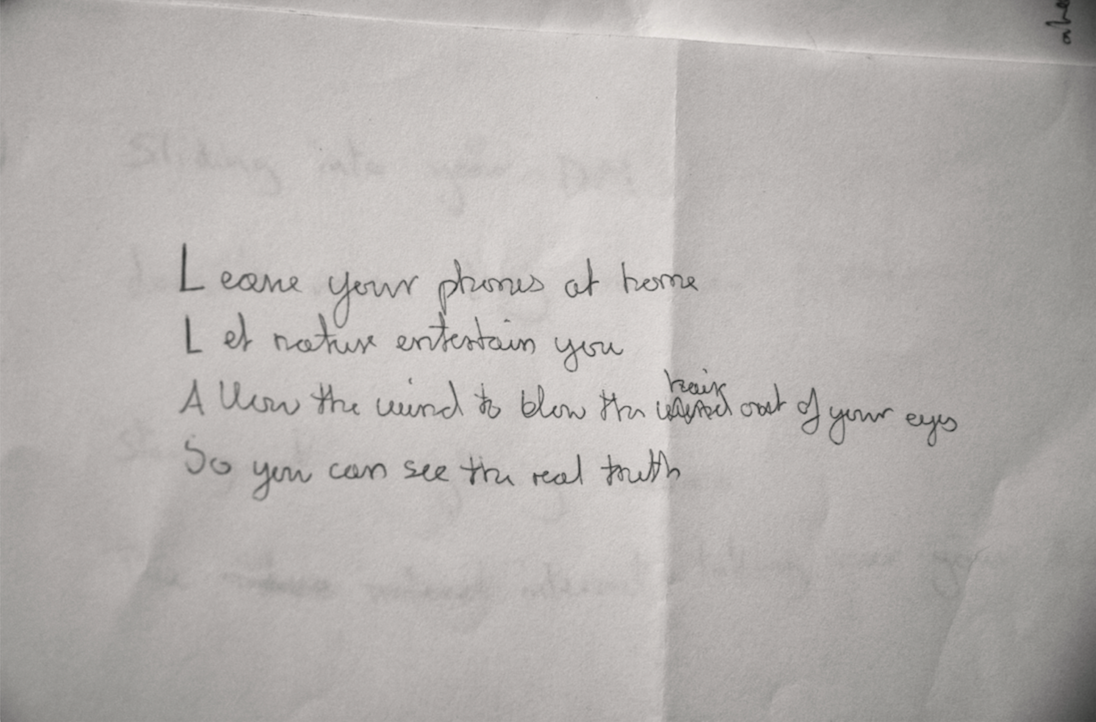

We asked the students to think about how we perceive nature today, and invited them to compose their own poems in response to the themes and issues raised by Dorothy and William’s writing. As we read over the poems composed by the students, it was fascinating to see how many of them – the majority of the group, in fact – had fixated on the idea of more modern distractions from nature, and in particular, the role of smartphones in ‘filtering’ nature for us in a more literal way. While William’s poem admonishes its addressee to abandon books and ‘hear the woodland linnet’, the year ten pupils from Keswick School used their poems as a chance to reflect on the need to abandon their phones and enjoy nature in its own right. Many of the poems focused on the idea of opening your eyes – perhaps connecting to the motto of Keswick School, levavi oculos, ‘I lift up my eyes’, which in a longer form is also the motto on the coat of arms for Cumbria as a county – Ad montes oculos levavi, ‘I shall lift up mine eyes unto the hills’. The students urged each other to ‘Lift up thy eyes / from the screen filled with lies’:

They lamented ‘The views that rival any other in the land, / Ignored by these kids, for a devise in their hand / Open your eyes.’ Yet these poems also celebrated the enjoyment of nature that young people, at least those growing up in Cumbria and other rural settings, still very much have. One poem proclaimed:

Year by year the fieldmice breed,

and green shoots sprout from every seed,

After all this trouble the birds still sing

Oh nature! what a marvellous thing.

Others balanced the use of technology alongside enjoyment of nature, one observing poignantly:

Zoom in on a picture but know

in the real world nature has

a higher resolution than any screen.

Look up to the trees, to the branches and leaves.

Notice the veins that weave

across the surface like a thread,

unravelling like a map to the road ahead.

It was fantastic to see this group of pupils enjoying and thinking carefully about their engagement with nature through the poetry and diaries of William and Dorothy Wordsworth. Our hope is that that is what these soundpieces of young people reading and discussing the work of the Wordsworths, and the enjoyment of nature, will encourage, along with the Wordsworth Trust’s work on Reimagining Wordsworth more broadly. Young people today can still get a lot out of both poetry and nature, as illustrated by the poems these year ten students produced at the Wordsworth Trust. It is with one of these poems that I will end, a poem that again deals with the intersection of nature and technology:

Eyes fixated on a glaring screen

human turning into robots,

surviving on wifi and phone signal,

they come alive as their

battery dies.

If you only looked up just

long enough to see the

mesmerising beauty of shimmering

lakes and the staggering

beauty of the mountains rising, breathtakingly from

the ground.

The moment ends

as the addictive phone looms

up from the pocket and

snaps the “insta worthy”

shot. #beautifulview.

Photographs by Kate Sweeney, doctoral candidate at Newcastle University (School of English). This post originally appeared on the Wordsworth Trust website. You can read more about the project here.

Thanks go to the following people, without whom this project would not have been possible: Lucy Stone, Michael Rossington, Sarah Rylance and Evie Hill (Newcastle University), Jeff Cowton, Bernadette Calvey, Melissa Mitchell, and Susan Allen (Wordsworth Trust), Tracey Messenger, Helen Robinson, and the Students of Keswick School, Deirdre Wildy (Queen’s University Belfast), Robert Macfarlane (University of Cambridge), sound artists Conor Caldwell (Queen’s University Belfast) and Danny Diamond, and project leaders Jemima Short and Kate Sweeney (Newcastle University).