Dr Lucy Pearson

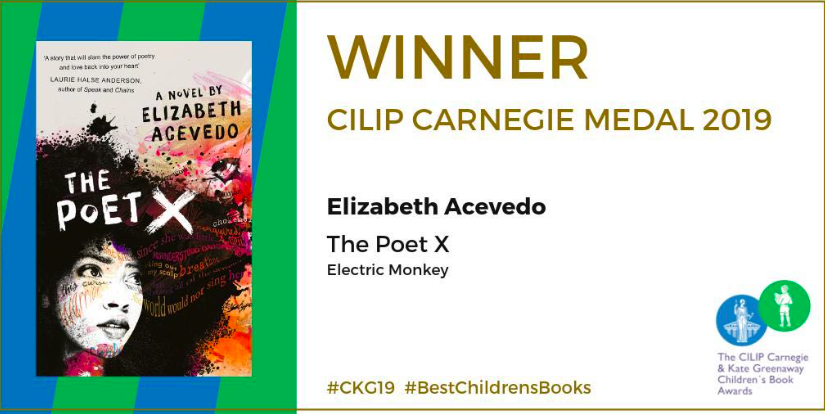

This year is a landmark for the CILIP Carnegie Medal: for the first time ever, the award goes to an author of colour, Dominican-American Elizabeth Acevedo. Acevedo’s verse novel The Poet X is a sensitive and nuanced depiction of the life of a young Dominican American. It’s striking that the novel won not only the main prize, but also the inaugural ‘Shadowers’ Choice’ award: there’s often a divergence between the shadowers’ favourite (as expressed through the Shadowing website – this is the first year there’s been an actual award) and the judges’ choice. This is definitely not because of a lack of competition – in fact this year’s shortlist was particularly exciting and included many worthy contenders – but I think it reflects a key characteristic of the novel: it’s simultaneously boundary-pushing and immediately familiar.

The verse novel has grown in popularity in YA circles in the last few years (Sarah Crossan’s novel One won the Carnegie in 2016) but it’s still a relatively new form, and one which is exploring the boundaries of form as a means of expressing the YA experience. Acevedo uses the form of slam poetry to explore questions of voice and voicelessness for her bilingual protagonist Xiomara, caught between the strict religious views of her Catholic mother and her own sense of herself and her place in the world. Xiomara’s experience is particular to her place, her culture, and her historical moment. Yet the book also has a universal resonance in the way that the best books do. As someone who was a young woman more than two decades ago, growing up not in Harlem but in provincial County Durham (in a decidedly monocultural environment), I was moved by Acevedo’s powerful expression of female desire and the experience of being in the body of a young woman. The book spoke to me, and spoke about experiences which I rarely see on the page. I think this combination of newness and ‘universality’ is what made the book speak to both the adult judges and the child shadowers.

By coincidence, the day the award was announced was the same day that my article with Karen Sands-O’Connor and Aishwarya Subramanian on Prize Culture and Diversity in British Children’s Literature. Part of a special issue of International Research in Children’s Literature on ‘Curating National Literatures’ (also edited by us), this article provides a context which demonstrates just why it’s significant for the Carnegie Medal to be awarded to an author of colour for the first time. We show that despite a genuine desire to promote ‘quality’ children’s literature, in practice mainstream children’s book awards in the UK have tended to uphold a view of quality which is white, English and (largely) middle-class, and to exclude the voices of Britain’s Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic (BAME) communities. This was precisely the concern voiced by many participants in the event which prompted our special issue: the Diverse Voices?Symposium jointly hosted by Seven Stories: the National Centre for Children’s Books and Newcastle University in 2017. That year’s Carnegie Medal shortlist had seen widespread criticism of the Carnegie Medal after the longlist failed to include a single BAME author: speaking at the symposium, YA novelist Alex Wheatle commented that ‘otherness, that feeling of being different wasn’t quite adjudicated for’. What our research for the article revealed was that children’s book prizes only represent a diverse range of voices when they are consciously working to ‘adjudicate otherness’: in other words, good will and a genuine belief in ‘objective’ criteria are not enough to ensure a broad understanding of literary quality. Only conscious engagement with the question of how literary quality intersects with wider culture ensures that the idea of literary quality isn’t shaped by unconscious biases.

The Carnegie Medal has a long tradition of engaging with wider culture. It was set up in 1936 with an activist mission: to encourage publishers to produce high quality children’s books. The late 1960s saw a new era of activism as the library profession expanded, prompting changes to the Medal which enabled radical new winners such as Robert Westall’s The Machine Gunners(1975). And since 2017, CILIP has once again engaged with the hard work of creating radical change, beginning with a Diversity Review of the CILIP Carnegie and Kate Greenaway Awards led by Margaret Casely-Hayford, and continuing with the implementation of many of that report’s recommendations. It’s this hard work which has produced a radically different shortlist: one which featured four authors of colour and produced the first ever win by an author of colour.

Elizabeth Acevedo has said that the inspiration for The Poet X was her desire to meet the needs of young readers who asked ‘Where are the books about us?’ It’s fitting, then, that her book has received the award in a year when CILIP have done a great deal of work to consider how the Medal might better reflect a wide range of readers. There’s still work to be done: it’s notable that this year’s shortlist continued to reflect a sense of race as something which is ‘out there’, not an integral part of UK life. Only one BAME author was shortlisted, and Candy Gourlay’s excellent novel Bone Talkis a historical novel. In the future, I’d like to see the Carnegie Medal go to a book which reflects one of Britain’s BAME communities in the nuanced, vivid way that Acevedo depicts the Dominican American experience. My hope is that the work so far will help to bring about change in the area the Carnegie Medal was originally meant to influence: the UK publishing industry. The more the Carnegie Medal and other prizes champion a wide range of voices, the easier it will be for publishers to ‘take a chance’ on a new voice, or to invest their resources in promoting books which don’t align with the literary mainstream. The varied, stimulating Carnegie shortlist this year, and the unanimous enthusiasm for Acevedo’s compelling voice, demonstrates that work can bring about radical change.