Professor Kim Reynolds

One of the most laborious – and often dispiriting – aspects of preparing a manuscript for publication is obtaining permission to reproduce words and images. However, I had some heartening and illuminating experiences when contacting the estates of the writers and artists whose work I wanted to reproduce in Left Out: the forgotten tradition of radical fiction for children in Britain, 1910-1949 and the companion volume, Reading and Rebellion, an anthology of radical writing for children, 1900-1960 (co-edited with Jane Rosen and Michael Rosen, forthcoming 2017). It seems progressive thinking and generosity of spirit passed on through generations. Many of the creative individuals whose work is central to both books gave their time and talent for free as a way of helping the rising generation prepare for the task of managing the challenges confronting what was then called ‘civilisation’. Those who represent them today were generally excited about the two books and generously gave permission for the work to be reproduced at no cost. More importantly, they also shared information and material about their relations.

An example is Jane Rabagliati, step-daughter of the brilliant graphic designer and illustrator, George Him (1900-1982). As well as giving me permission to reproduce material, Jane invited me to her house to see the archive she has assembled relating to Him’s work, including his fertile professional partnership with Jan Le Witt (1907-1991).

Working under the name Lewitt-Him, the pair, who began working together in Warsaw in 1933, arrived in London in 1937. They had already produced some ground-breaking children’s books such as Locomotive (1938, first published in Poland) based on the text by the distinguished Polish poet Julian Tuwin. Tuwin’s sound-poem is perfectly complemented by the modernist style of the Lewitt-Him illustrations (a new edition of the book will be published by Thames and Hudson later in 2017).

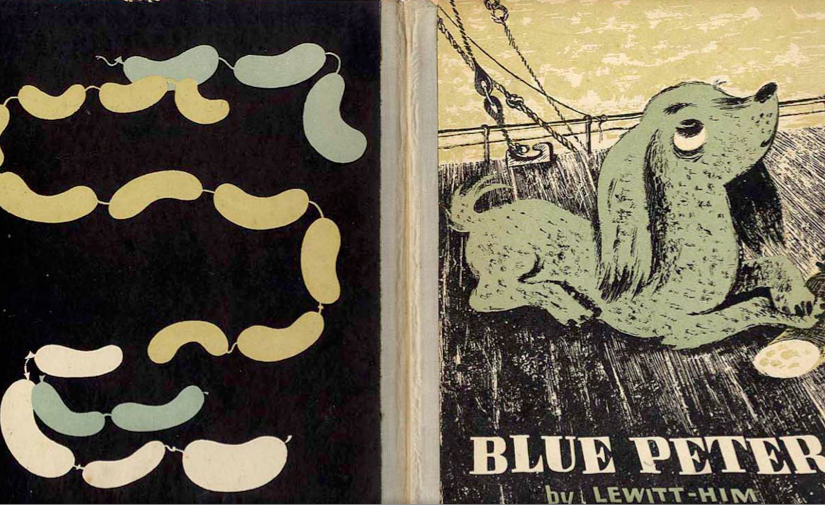

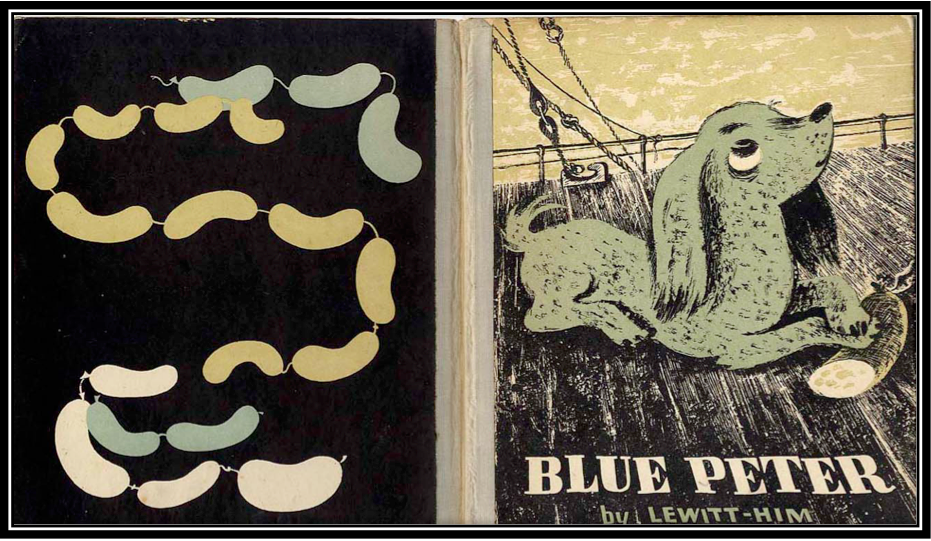

Once in England, the pair created several high-quality children’s books, being among the first illustrators working in the UK to introduce modernist elements for this age-group: their style leaned towards abstraction and borrowed elements from Surrealism and Cubism. A typical example is Blue Peter (1943), with text by Jan Le Witt’s wife, Alina. This story about a blue dog born to a white mother who is persecuted but eventually finds a home on Blue Dog Island is a parable that no doubt appealed to George Him, a Jew who witnessed the Russian Revolution, was living through the persecutions and atrocities of the Holocaust at the time of publication, and was a supporter of the project to create a Jewish state.

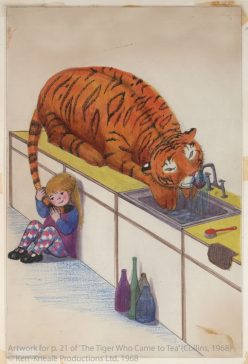

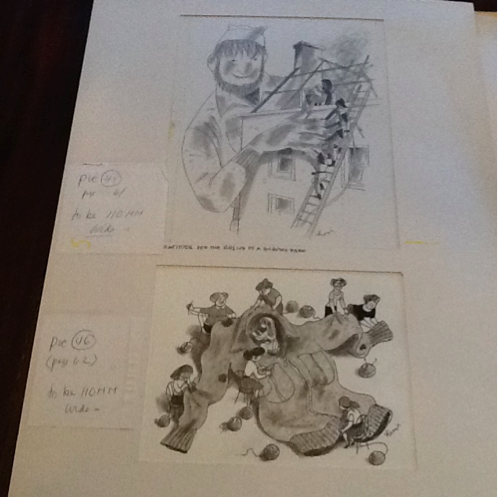

Children’s books were a relatively small part of Lewitt-Him’s output, but after they disbanded in 1955, George Him went on to illustrate a number of popular works on his own. When no longer working as part of a team, his style became more traditional and decorative, but the richness of his palette and the narrative intelligence that informs his compositions is impressive. It is possible to view his illustrations for Frank Hermann’s Giant Alexander books (more than 600,000 copies sold world-wide) at Seven Stories, the National Centre for Children’s Books. Him also worked with Leila Berg on the Little Nipper series; Berg’s archive, too, is held at Seven Stories.

Several of the books in Jane Rabagliati’s archive were entirely new to me, among them the books about King Wilbur the Third which were among several Him did for television. This link takes you to a page where you can see samples of his television graphics. These are not as innovative as the earlier work, but they capture well the style of the times and the particular fusion of book and television associated with programmes such as Jackanory.

I wrote a bit about some Lewitt-Him books in Left Out, but there is much more to be said about them and the work of Him on his own. A couple of years ago the publishing wing of the Tate Gallery reprinted The Football’s Revolt, and now Thames and Hudson are reintroducing Locomotive. It seems a good time to be thinking about how, together and singly, Lewitt-Him influenced children’s publishing in Britain.