Dr Emily Murphy introduces her new book, Growing up with America: Youth, Myth, and National Identity, 1945 to Present

deceased friend

In the aftermath of George Floyd’s death, a number of protests emerged internationally to support the Black Lives Matter movement. It’s a turn that raised with urgency the question of who belongs in America and how the rights of the nation’s marginalized citizens can be protected. As the harrowing footage captured for Floyd’s case revealed, it’s not always lawmakers who can be trusted to protect these rights. This is a message that American teenagers have tried to make clear both on the silver screen and in public protests. In Angie Thomas’s The Hate U Give (2017), protagonist Starr Carter is left devastated after her childhood friend is unjustly shot by a policeman. In the 2018 film adaptation of this young adult novel, one of the most powerful images is Starr’s raised fist as she leads a peaceful protest. In this moment, Starr not only represents the Black Lives Matter Movement but also the figure of the rebel that is often associated with American adolescence.

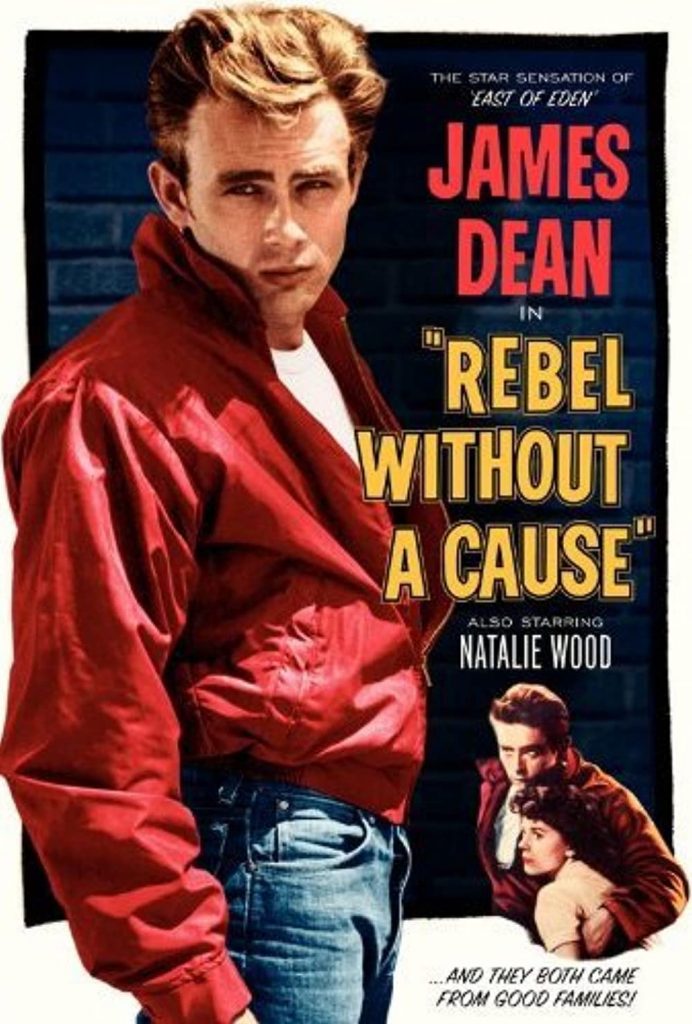

At the start of the 1950s, the image of the rebel teen was popularized both in response to the national mood, a time when the nation was anxiously trying to “grow up” and establish itself as a world power, and in response to a rapidly expanding youth market following an increase in birth rates during the “Baby Boom.” Heroic male figures—all white—included a youthful cast such as James Dean in Rebel Without a Cause (1955) and drew upon Western myths of the frontiersman. These new bad boys moved the frontiersman out of the flat plains of the West and into the cookie-cutter neighbourhoods of suburbia.

The suburban “bad boy” produced through popular culture supported Cold War rhetoric of the United States as an exceptional nation, one that was whitewashed and sanitized for mass consumption. But tucked away beneath these celebratory narratives of national power and might were stories of marginalized Americans, often told through the same figure of adolescence that gained currency through the teen icons of popular culture. In some of the most explosive literature of the decade, there are glimmers of the adolescent’s true potential as a rebel, which worked to upturn hundreds of years of history and give voice to those previously silenced.

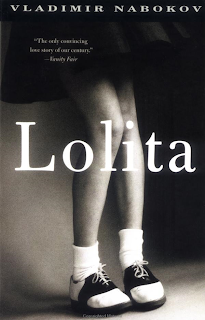

One of the most heart-wrenching, and perhaps most recognized canonical works of the period, is Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita (1955). In my book, Growing Up with America (2020), I argue that Lolita’s story of loss and suffering is reflective of the colonial violence of the nation. While her body is often described as lean and muscular, it is the variation in her complexion that is intriguing: at times the light skin of the white girl that she is and other times a dark brown. Lolita might easily remind readers of a spoiled suburban teenager with the way she is described by protagonist Humbert Humbert, who takes advantage of the death of Lolita’s mother to pursue an unwanted sexual relationship with the young girl. But there is something haunting in the voice that Nabokov creates in this novel that strips away Humbert Humbert’s fantasy. Nabokov hints at this association in Lolita’s collection of American Indian handicrafts, and through other key moments within the novel. In a scene where Lolita is shivering from an unnaturally high temperature—importantly the illness that enables her ultimate escape from Humbert Humbert—Lolita is shown at her most vulnerable and these subtle associations come to the fore, urging readers to think about repressive systems of power that have silenced those who do not belong to a white (and often male) majority. Lolita is what I call a “virgin girl,” a figure that dispels the myth of an empty and conquerable land that is devoid of people, which helps to justify westward expansion in the nineteenth century and neocolonialism beyond U.S. borders in the twentieth century and beyond.

While Lolita remains firmly positioned within white middle-class suburban culture (she is, after all, a white girl no matter how she is portrayed), her character functions as a quiet act of subversion that helped to upturn national myths that celebrated white masculinity within American culture. That is, Lolita’s body still alludes to the history of colonial violence against those who were marginalized due to their race through her association with American Indian culture, a connection I argue in my book that Nabokov intentionally developed. Lolita’s very often silent protest to such injustices grows louder over time as it is joined and made stronger by the contributions of Native women writers including Linda Hogan, Lesley Marmon Silko, and Louise Erdrich. Their work serves to demonstrate the ways in which American literature has worked to light a fire of rebellion to promote positive and meaningful change in the nation, opening up spaces to revisit the question “What does it mean to be an American?” and reminding us that, so long as injustice persists, there will continue to be young rebels seeking to right these wrongs.

Emily Murphy is Lecturer in Children’s Literature at Newcastle University. Her book is now available for purchase from the University of Georgia Press. To reserve a space at the book launch event for Growing Up with America, register here. For guest talks, contact Dr. Murphy at emily.murphy@newcastle.ac.uk.