Today, Universal Children’s Day, the 20th of November 2017, the International Research Society for Children’s Research in Children’s Literature (IRSCL) issues a Statement of Principles, concerned about the ways in which contemporary geopolitics curtail academic freedom.

This summer, the IRSCL convened its 23rd biennial congress in Canada. More than 20 percent of the scholars whose papers were accepted were unable to attend due to radical economic disparities and restrictive travel policies in the world.

The IRSCL is worried by the current xenophobic situation as it curtails academic freedom. The free flow of people and ideas across borders has to be defended anew, says Lies Wesseling, President of the IRSCL.

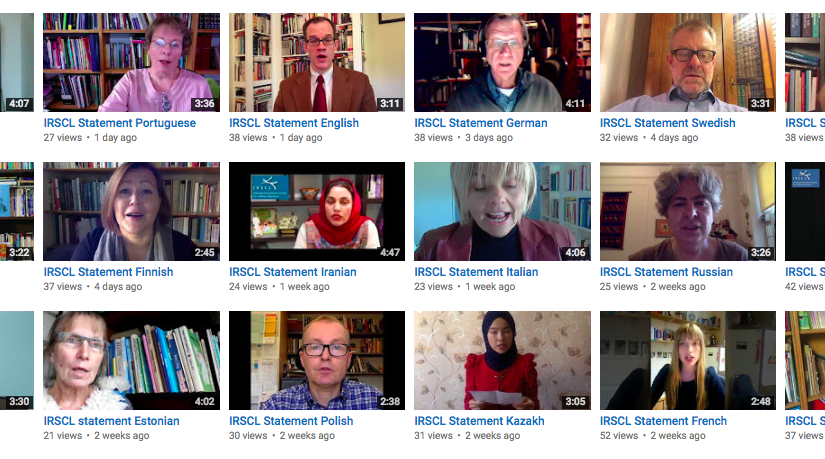

For this reason, the IRSCL today issues a Statement of Principles, which explains why scholarship can flourish only in a world with open borders. The statement is in the format of a collection of videos featuring IRSCL members reading the statement in their native language.

The statement is issued on Universal Children’s Day to emphasise not only the importance of our research, but also of children’s literature’s potential to foster empathy, nurture creativity, and imagine a better world, says Lies Wesseling.

The IRSCL is an international scholarly organisation dedicated to children’s and young adult literature with 360 members from 47 different countries worldwide. This announcement has been adapted from the IRSCL press release. You can learn more about the IRSCL on the IRSCL website and follow the IRSCL on Facebook.

Every second year the organisation arranges the IRSCL Congress, the world’s most international congress within the research field. Please read on for a report of this year’s congress by Professor Kim Reynolds.

IRSCL Congress 2017

Possible & Impossible Childhoods

Professor Kim Reynolds

The 23rd biennial gathering of the International Research Society for Children’s Research in Children’s Literature (IRSCL) convened at York University, Toronto at the end of July. Lasting 5 days, it was a full-on programme with more than 300 papers, and a programme of complementary events. Over the years I have come to prefer smaller, more tightly focused symposia where it is possible to hear most of the papers and have ample time for discussion and networking. This, however, was a beautifully constructed programme on the theme of ‘Possible and Impossible Childhoods’ with an emphasis on exploring the intersections between children’s literature and childhood studies. An added feature of this year’s conference was a much-deserved celebration of the work of Jack Zipes, who had several books appear in this, the year of his 80th birthday. Jack has not only been a great contributor to children’s literature scholarship through his publications and projects on fairy tales, storytelling, translation and adaptions of children’s books, but also a good friend to scholars young and old and a great ambassador for both children’s literature and childhood studies. One of his recent publications looks at retellings of tales about the sorcerer’s apprentice, popularised in the Disney film Fantasia. Zipes shows that one strand of these tales is unusual for showing how those who are enslaved or otherwise have little power manage to challenge elites and transform the status quo. For those of us interested in the use of magic in children’s literature, it’s an important new resource.

Perhaps I enjoyed this conference more than other huge events I have been to recently because I chose which sessions to attend more carefully. There are always competing pressures to hear new voices, as well as to attend sessions by students and friends, to learn what established figures are thinking, and to support those who may be at the margins of a conference in terms of language and corpus. So a tip to those who are new to the conference scene – be both a little selfish and a little adventurous as you plan your schedule so that you get the maximum from what can be a costly experience in terms of time, energy and money.

Unlike, say, the main annual conference of the Children’s Literature Association, another huge event with a strong US/Anglophone focus, the IRSCL congresses are always truly international. Those who attend them tend to be very welcoming to colleagues from all countries and at all stages in their careers, for this society was formed precisely to support children’s literature scholars, who even today, when the subject is more established, often find themselves rather isolated in their own institutions and countries. It is a fine forum for discovering new kinds of primary materials, new methodologies, and potential collaborators.

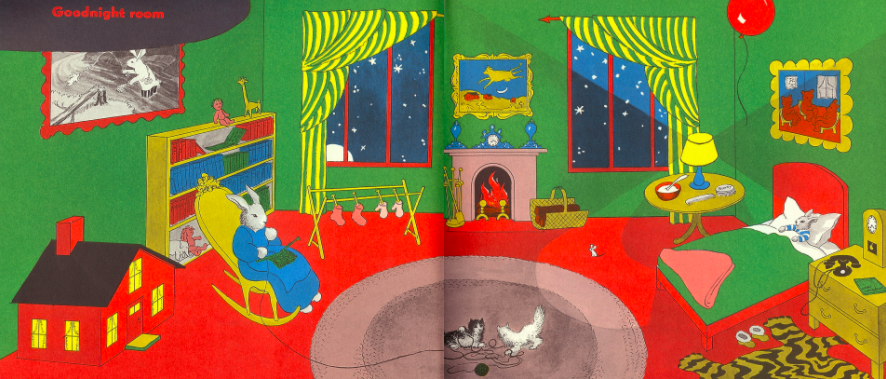

For me some highlights this year included a plenary by Robin Bernstein, a cultural historian based at Harvard, who developed her work on the performative nature of children’s literature in the form of a lecture on ‘going-to-bed-books’. In a stylish and witty lecture she managed to convince me that books can be examples of ‘performative utterances’, meaning they don’t reflect existing reality but change it. In this case, the books change the moment from not time to go to sleep to one in which sleep is embraced.

Robin also works on race, and she was one of many voices who encouraged us to examine our default assumptions and understanding of what we mean by inclusivity. Although I have always found IRSCL to be very inclusive, it is true that the preponderance of participants come from Europe, North America and Asia, and so work remains to be done. Robin’s lecture was introduced by Philip Nel, whose new book Was the Cat in the Hat Black? addresses this issue in an engaging but challenging way.

I was also very taken with a highly unusual variation on the WWII prisoner of war story told by a young scholar from China who discovered in the stacks at SOAS (School of Oriental and African Studies, London University) a magazine produced by children who were incarcerated in a school in occupied (by Japan) China. Although it was technically a prison camp, the missionaries who ran it managed not only to keep a semblance of normal life running for the international group of students held there but also to make it a happy and rewarding time in their lives. They played baseball, studied for their exams, attended meetings of Scouts and Guides – complete with uniforms – and launched a magazine which continues to this day. When the war was over and the children were dispersed, it provided a valuable social network. An equally fascinating though chilling paper looked at how the Turkish government has been rewriting traditional folk and fairy tales in the service of the current regime’s ideologies. Altogether, I came away intellectually recharged, more than ever aware of the political and cultural significance of children’s literature, and convinced yet again that these assemblies of scholars are a genuinely important part of international co-operation and intellectual development across countries.

Silence and Silencing in Children’s Literature, the 24th Biennial Congress, will be taking place in Stockholm, Sweden 14-18 August 2019. Information will be regularly updated on the IRSCL Congress 2019 website.