Dr Hazel Sheeky Bird

Late last week we received the sad news that Elaine Moss had died, aged 96. Over a long career as a children’s librarian, book reviewer, critic, broadcaster and writer, Moss’s impact on British children’s books has been considerable. Never losing sight of the children in children’s books, she was a vociferous advocate for the centrality of good books to children’s literacy.

The great impact that children’s librarians have had on British children’s books has never really been acknowledged. As such, Moss’s name and work may well be little known today. The fact is that for over 30 years, Moss worked tirelessly not only to promote knowledge about children’s books but to also get them into the hands of children, teachers and parents. On receiving the Eleanor Farjeon Award in 1976, the Children’s Book Circle noted that ‘it is not only her constant efforts to promote the cause of children’s books that single out Elaine Moss’s contribution; it is her unique concern both with communicating her own enthusiasm for books as a medium of enjoyment and with bringing books for children to children’ (quoted in Signal 23, May 1977).

Looking back on her professional life (Signal 91, Jan 2000), Moss described the beginnings of a career rooted somewhat in happenstance. Born in London in 1924, she recalled that neither of her parents was particularly bookish but she remembered her mother reading Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland to the family, and Moss herself was a keen reader. At 16, due to the Second World War, she found herself school-less. As she was fond of reading, her mother sent her off to the local library to ask for a job . . . they put her in charge of the children’s library. She read History at Bedford College giving rise to a particular interest in children’s historical fiction in later life. After undertaking teacher training, she found herself working at a boarding school in Haslemere, largely teaching English to refugees from Europe. This was followed by chartership examinations to become a librarian, although not a children’s librarian, such a role did not exist at that time.

It was Moss’s experience of working with legendary children’s editor Grace Hogarth that marked the real turning point in her career. Having had to give up work on getting married, in 1955 she went to work as a part-time PA for Grace Hogarth, who at that point worked as a scout for four American publishers. A self-described ‘Grace’s girl’ (Signal 78, Sept 1995) she credited Grace Hogarth as her mentor. By 1955, Hogarth already had a network of women who worked for her as readers while also raising their families. When Grace Hogarth set up Constable Young Books, Moss started reading for her there. It was here that Moss was introduced to fellow Grace’s girl, Nancy Chambers; this was to prove fortuitous for both women, marking the beginning of a long association between them.

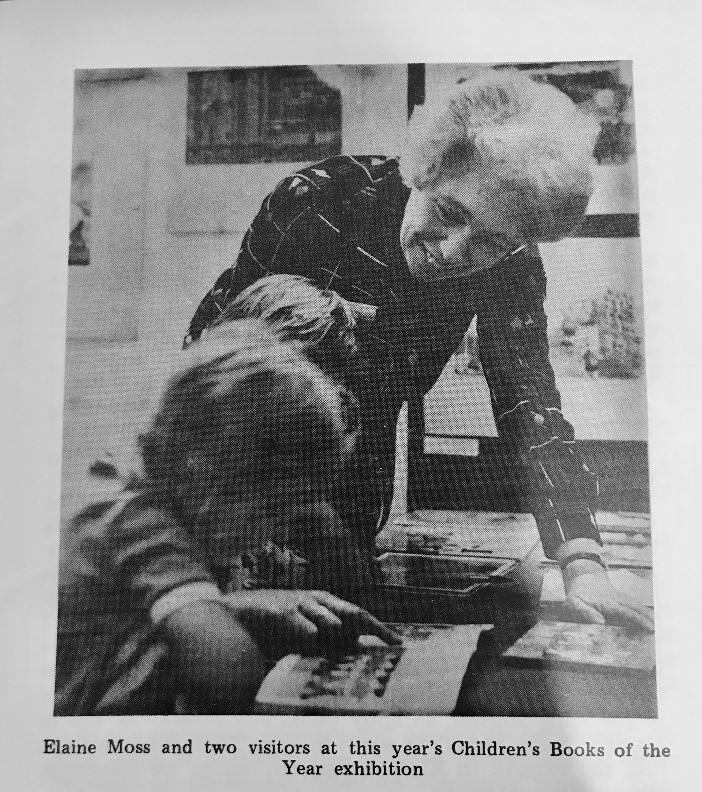

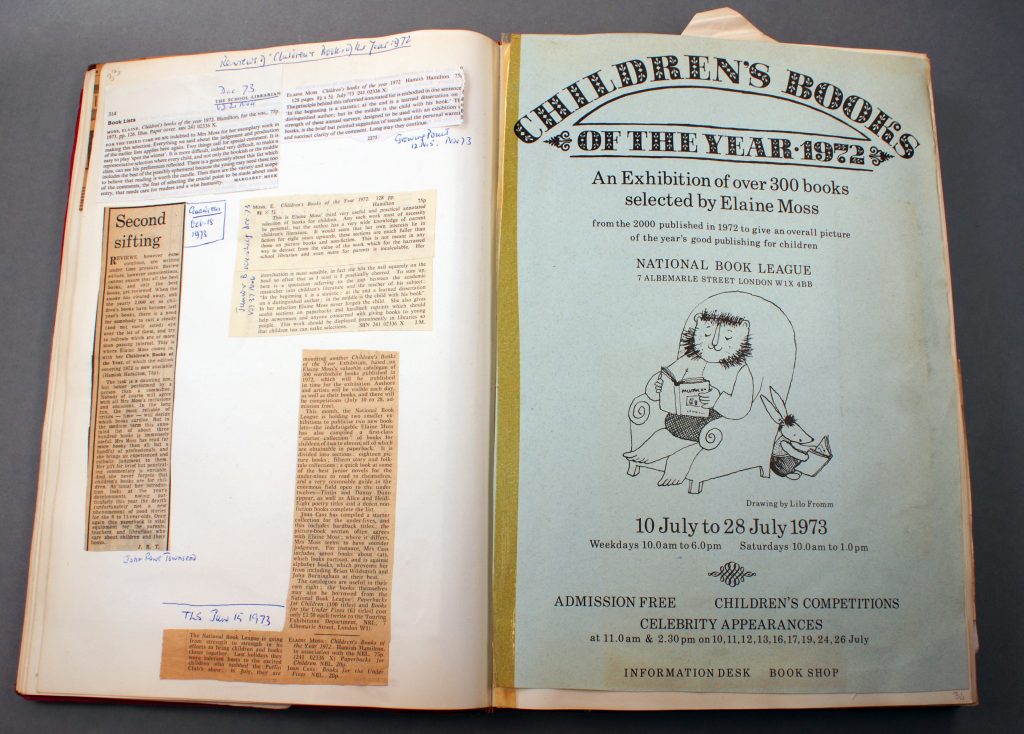

By the 1970s, Elaine Moss was a prominent figure in her own right. As well as broadcasting on popular programmes such as Women’s Hour, from 1970 she selected the National Book League’s Children’s Books of the Year exhibition, for which she wrote its influential annotated catalogues. In an era which is often regarded as a ‘second golden age’ of children’s literature, Moss made an important contribution to the critical discourse around the subject, contributing articles to mainstream publications including The Times, The Daily Telegraph, The Guardian, the Times Literary Supplement, and The Spectator, as well as to specialist children’s book publications like Children’s Book News. In so doing, she helped to define children’s literature as an important part of British cultural life. Significantly, she retained a foot in the real reading lives of children by continuing to work as a part-time librarian at a primary school.

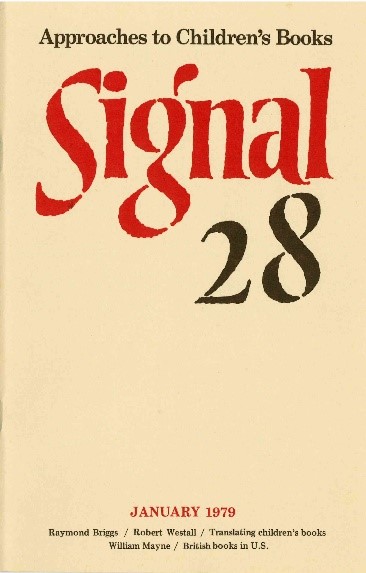

Moss’s friendship with Nancy Chambers, along with their shared desire to give children’s books the serious attention they deserve, led to Moss’s close involvement with important children’s literature journal Signal: Approaches to Children’s Books (1970-2003), edited by Nancy Chambers. Moss wrote 46 articles for Signal over its 100 issues, contributed an important chapter on ‘The Seventies in British Children’s Books’ to The Signal Approach to Children’s Books (Kestrel, 1980) and, with Nancy Chambers, compiled the indispensable Signal Companion: A Classified Guide to 25 Years of ‘Signal: Approaches to Children’s Books’ (Thimble Press, 1996). This body of work offers today’s readers a clear insight into Moss’s breadth of knowledge and the strength of her advocacy for children’s literacy through literature.

Speaking at the twenty-second IBBY congress in 1990, Moss characteristically argued that uninspiring reading schemes did not produce real readers and that, ‘If literacy in the developed world is to be worth acquiring in more than the functional sense, we should now be concentrating our efforts on ensuring that children of all social and economic backgrounds are given the opportunity to sample, at an early age, the best stories and poems that folklore, true poets and authors of integrity can offer’ (Signal 64, Jan 1991, p. 17).

Looking back at Elaine Moss’s pieces in Signal it is striking how relevant so much of her work remains. Two articles in 1978, ‘Them’s for the Infants, Miss’ Parts One and Two (Signal 26, May and Signal 27, Sept) argued strongly for the use of picturebooks with older children. Like other Signal contributors, Moss went on to develop this work into a specialist Thimble Press publication: Picture Books 9 to 13 was first published in 1981 and by 1992 was in its third edition. It remains an invaluable guide.

Today, Elaine Moss’s work in Signal is still accessible and relevant. Her voice is also a strong presence in the Aidan and Nancy Chambers archive, held by Seven Stories, the National Centre for Children’s Books. As well as editorial material relating to her many contributions to Signal and Thimble Press, it contains over 30 years of correspondence that offers unique insight into Moss’s work and the British children’s book scene from 1970 to the present. Anyone interested in knowing more about Moss and her work is fortunate as she donated her collection of 750 picturebooks to Seven Stories in 2003, and her fascinating collection of scrapbooks in 2009, which document her own contributions to multiple publications and offer a picture of how discourses around children’s books changed over the course of the 20th century . It is only fitting that Elaine Moss, who made such an important contribution to the promotion of British children’s books, is present in this nationally significant collection.

Banner image: Quentin Blake sketch drawn on being interviewed by Elaine Moss for Signal. Originally printed in Signal 16, Jan. 1975, p. 33.