Books always were my best friends; ever since I was a child they shared with me their facts and knowledge, their flights of imagination, with fun, dread and suspense.

There is always a bond between the author and reader, every book is a bridge, having something different to offer […] Books are lasting, they do not lose their leaves in autumn as trees do.

Tomi Ungerer, A Velocity of Being: Letters to a Young Reader 2018, 216

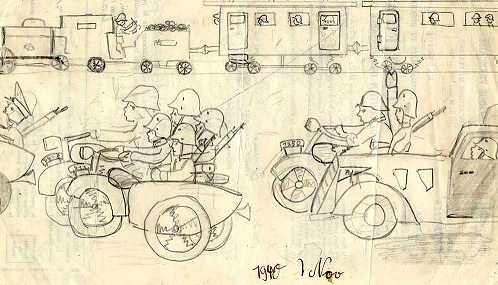

The Tomi Ungerer I first knew was not Commandeur de la Legion d’Honneur, the prolific illustrator and trilingual writer of 140 books. Rather, he was Tomi Ungerer, the precocious child artist who, in the summer of 1940, aged 8, witnessed the Nazis invade his hometown in Alsace. A few months later, he recorded this sight on paper:

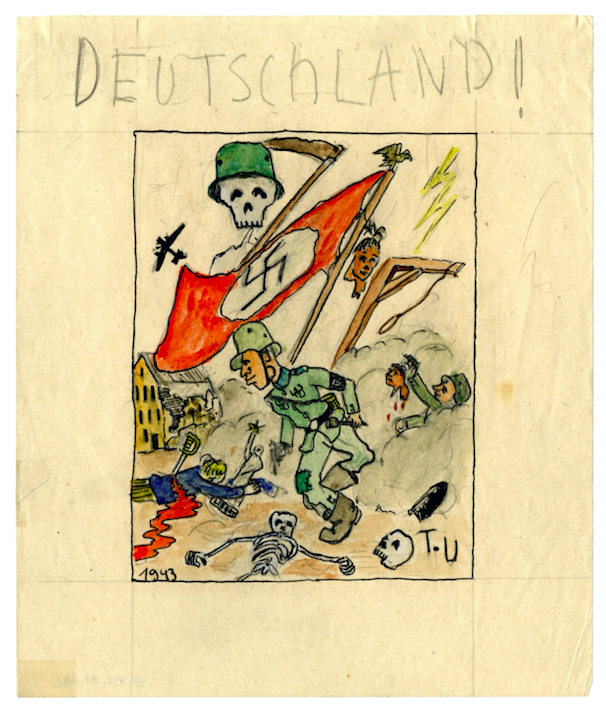

Many years after that date, this pencil drawing would illustrate his memoir of his childhood under the Nazis, first published in French as À la guerre comme à la guerre (1991, in German as Die Gedanken sind frei, 1993 and in English as Tomi: A Childhood Under the Nazis, 1998). By the time of this drawing, Ungerer could only sign his drawings TU within the safety of his home; in Nazi-occupied Alsace he had to change his name from Tomi (Jean-Thomas) to Hans (Johann). Street names, as well as resident’s first names changed from French to German; French books and berets were banned and one word of French, one bonjour, one merci would land you in an internment camp. Ungerer’s sister, Genevieve, who worked at the government prefecture during the war, would take home formulas and certificates of military allocations, and he would draw on the back of these. Ungerer drew, among other subjects, images of the Nazis; had they been discovered…

Thankfully, they were not. Tomi Ungerer’s mother conserved 500 of the drawings he made in his childhood (both before and during the war), and they formed part of the collection for the Musée Tomi Ungerer – Centre Internationale de L’Illustration in Strasbourg, which holds 11,000 graphic works by Tomi Ungerer and collections by artists such as André François, Maurice Henry and William Steig.

I have been fortunate to work on the collection of child art as part of a doctoral project exploring the significance of juvenilia in the formation of artists whose backgrounds include exile and war.

One of my museum visits coincided with the press conference for the museum’s 10th anniversary, and the museum curator, Thérèse Willer, kindly invited me and introduced me to Tomi Ungerer. I was very moved. There were many important people present, my spoken French was – and still is – abominable, but Tomi Ungerer took leave of them from time to time that morning to hear about my project and talk to me about his life, his influences. ‘Books are everything,’ he told me. Books? I was surprised. Was it not drawing that should have been everything to this remarkable artist? No, books, he said, books that he had read as a child had marked him for life.

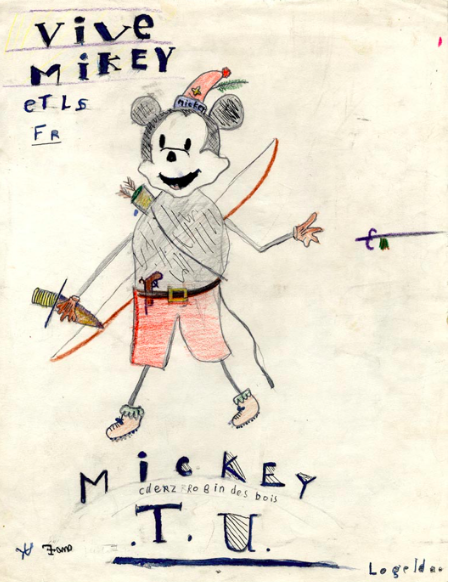

Back in the museum library, Thérèse Willer showed me the Benjamin Rabier albums that Tomi Ungerer’s brother and sisters had handed down to him and contained his first scribbles, Jean de Brunhoff’s L’ABC de Babar, one of the few books that had been Tomi Ungerer’s very own as a child and that would in part inspire his Mellops family, the family of pigs in his first published children’s books.* She also spoke with me about the young Ungerer’s reading of Le Journal de Mickey and the books by the Alsatian artist Hansi (Jeans-Jacques Waltz). Mickey Mouse appears in drawings Tomi Ungerer made before and during the war: when Tomi Ungerer’s world was turned upside down, Mickey Mouse was a figure remnant from his pre-war world that provided him a reference point as he sought, on paper, to navigate the place his home had become.

Many of the soldiers he drew at this time (when not at school!) are not those of the Second but First World War; Tomi Ungerer’s dislike for the Nazis was in great part informed by the anti-German propaganda Hansi wrote and illustrated in his children’s books around the time of the so-called Great War.

the books read in childhood lay the foundations of a writer’s literary aesthetic; they provide the models, the anti-models, and the springboards for subsequent generations

Kimberley Reynolds, Radical Children’s Literature: Future Visions and Aesthetic Transformations in Juvenile Fiction 2007, 9.

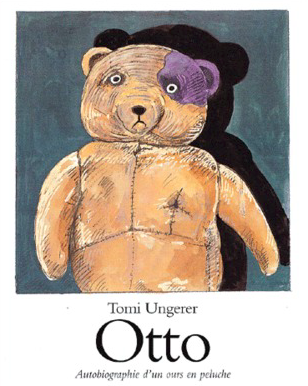

In many ways, Hansi’s books became the anti-models for Tomi Ungerer’s work as an adult that fought against social injustice and prejudice and for pacifism. Firmly believing that children should not be shielded from the reality of war, his picturebook, Otto: the Autobiography of a Teddy Bear, which fictionalises some of his own childhood experiences, does not shy from the violence and persecution of the Second World War; schools in France often use the book to teach children about war and the Holocaust. Perhaps stemming from the role creativity played in his own childhood, he also strongly advocated for children to use their imaginations and stretch their minds (Ungerer always liked to include words in books child readers would not necessarily know).

On Saturday afternoon I saw that the Tomi Ungerer Museum had changed the profile picture on their Facebook page: a black circle; their cover photo a black banner. What exhibition is this for, I wondered, what is Tomi commenting on with this blackness in his latest artwork. Then I realised. These changes were not for an exhibition. There was no new artwork. Tomi was dead. Yet, as I learned the following day, yesterday, black was not only appropriate for marking our loss of Tomi, but also to represent one of his philosophies. In a video clip the Ungerer family posted, Tomi explains:

When I say far out is not far enough, it means that no matter how far you’re thinking […] no matter how far it is, it’s still not far enough. Because one challenge [to be] worthy at all has to be followed by a greater challenge. It’s the unknown, that’s what’s really fantastic about death and death is to be welcomed, and when I die I’ll find out what’s behind the far out. Maybe there’s nothing. But nothing is fantastic too, because if you’re faced with nothing, you can fill it up with your mind.

Tomi, whatever may or may not be behind the far out, may your incredible imagination serve you well.

My thoughts at this time are above all with Tomi Ungerer’s family and museum staff. For blog readers unfamiliar with Tomi Ungerer’s works, I encourage you to look at further examples of his child art on the museum website and details of his books for children and adults can be found on the Tomi Ungerer website.

Lucy Stone, doctoral candidate

*See Thérèse Willer’s Tomi Ungerer: Graphic Art (Éditions du Rocher, 2011).