This month I left Newcastle University for a new post at Leeds Beckett University where I am Professor of Teacher Education. I am thrilled to be given this opportunity to work in my chosen field at a new institution and looking forward to making a contribution to knowledge, practice and the work of teachers, student teachers and educators in that region, as well as (I hope) further afield. When the job was advertised it seemed like too good an opportunity to miss, although my first job application in 17 years was somewhat daunting. I found myself writing it on New Year’s Day and perhaps that was the clincher, with the hopefulness of a new year, the potential challenges seemed enticing. There were two additional pull factors. Firstly, I was born in Headingly (where the Carnegie School of Education at Leeds Beckett University is based), but left when I was two years old, so this felt like a bid to return to a forgotten homeland. Secondly, I had been to the Headingly campus the previous summer, on a warm sunny day when the parkland and redbrick buildings looked at their best, to attend a @WomenEd event. Perhaps this application was my response to the commitment the women at that conference were making to shaping and sustaining education through their own professional lives. So, cutting that story short, and via an interview in a box overlooking the cricket ground at Headingly (where the university occupy a stand) I have taken up the post. Time will tell what this will bring, but I look forward to it. But in looking forward I also look back.

My academic, professional and much of my social life has revolved around Newcastle University for longer than the nearly 18 years I have worked there. I joined the then School of Education in Joseph Cowen House in 1990, to do my PGCE with the relatively new tutor David Leat. Indeed I was the first candidate he ever interviewed for PGCE. My PGCE was the best transition to professional and educative life I could imagine, and David should take credit for this. It was a place where we explored ideas, made mistakes, learned to outgrow our embarrassment and naivety as new teachers, gained lifelong friends, and benefitted from mentoring and university tutoring which was absolutely based on the principles of critical friendship, subject enthusiasm and professional allegiance. We learned how to reframe our perspectives on teaching and learning, and worked hard to learn to teach our subject (Geography) with both rigour and freshness. This was pre-national curriculum and pre-QTS standards – a world becoming ever harder to recall! I had placements in Scotswood and Hexham (thank you to Dave Lockwood and Gordon Whitfield my mentors), and went on to be a ‘probationer’ in Durham (thank you to Ian Short for his pragmatic leadership and support) and later a head of department in Prudhoe (thank you to Bill Graham for his subject wisdom and patience). Much of my practice development and intellectual curiosity was supported by my work in partnership with the local authority advisors and colleagues from other schools, with particular shout-outs to Mel Rockett, Robert Peers, Anne D’Echavaria, James Nottingham and many others.

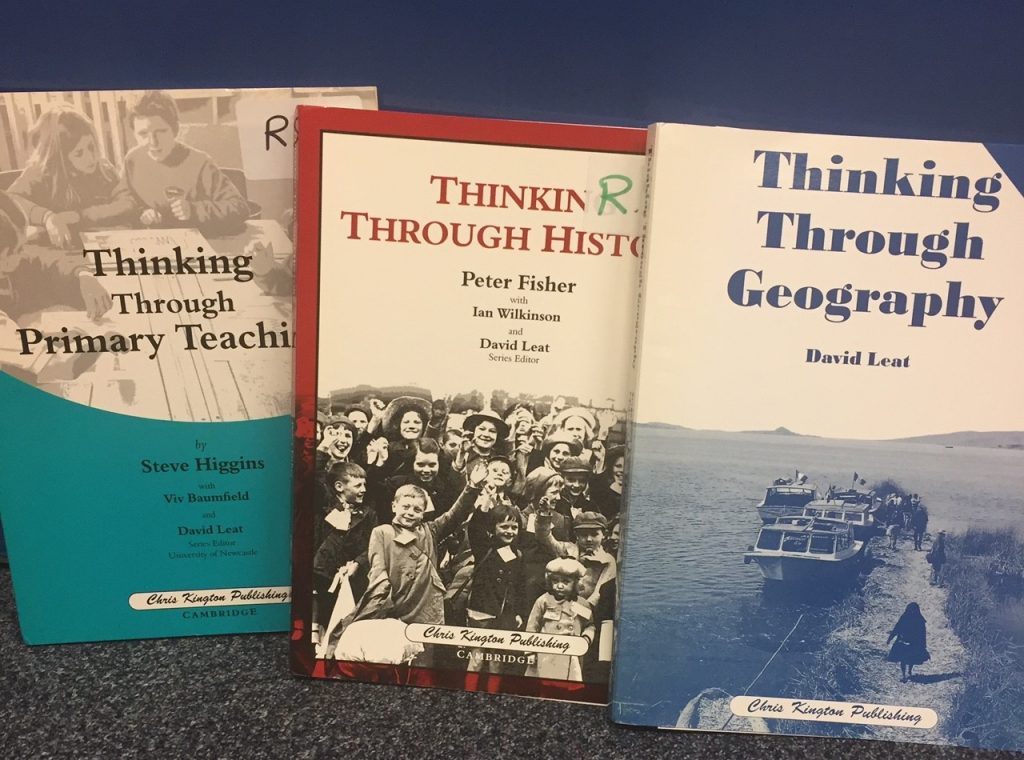

I have occasionally found myself in the right place at the right time, and the 1990s was just that for me. As a teacher I kept connected to the university in various guises. I was part of the Thinking Through Geography group, a PGCE mentor and occasional visiting tutor and a teacher-coach participant in a Schools Based Research Consortium project on teaching thinking skills. I joined the university in 2000, having left behind the beckoning era of teacher performance management, threshold pay and league tables. I was an enthusiastic Geography PGCE tutor, enjoying the buzz that job offered of working with a diverse group of motivated student teachers, helping them make sense of education from their new perspectives and helping to sustain local geography departments where so many of them went on to work. The legacy of the teaching thinking skills work was significant and became a core characteristic of both the Geography and wider secondary PGCE in the 2000s. My own interest in the work of mentors also provided continuity as I transitioned from that role to the university, and aligned with my experiences as a teacher coach in the research project. Over time I took the lead in the secondary PGCE and then moved on to look the various part-time Masters programmes. This gave me multiple opportunities to work with teachers from across the region, at all stages of their careers and in all educational sectors. In the last few years my particular interest has been developing the PGCert in Coaching and Mentoring modules. From my modules, and across the M.Ed and Ed.D programmes a significant learning experience for me has always been listening to teachers talk about their work and supervising their research. I have also enjoyed working more directly with a number of North East schools (including Hermitage, Cardinal Hume and Kelvin Grove) to develop and research approaches to professional learning and development, often through coaching. Thank you to all my Newcastle University students, and to the teachers, coaches and mentors I have worked with in schools. I have gained so much from working with you.

And so to my colleagues, without whom none of my enthusiasms for my work would have translated into practice. My teaching colleagues in PGCE and Masters programmes and my research colleagues in CfLaT have been the most amazing critical friends, collaborators and co-conspirators. The educational landscapes that we inhabit have changed radically over my 18 years at Newcastle University; initial and continuing teacher exists in a topsy turvy world which maps haphazardly onto the changes in the organisations we used to know simply as schools, but now as academies, MATS, teaching schools, (to name just a few), and both our university and the wider HE sector has been transformed through student loans, the REF and global league tables. Through this my colleagues, who are unfortunately too numerous to name individually, have been a constant source of inspiration and challenge. They know who they are, some are newly appointed, some have departed and others have worked alongside each other for many years. They are all people who care deeply that education works for all in society; that it offers individuals ways of making sense of their world and allows communities to thrive. Thank you to you all, for you have continued to teach me that education is of the people and for the people; wherever they (and we) are.