A learner from the Enterprise Shed (Newcastle University’s third MOOC) shared one of his favourite TED talks, in which Tom Wujec, a designer who has studied how we share and absorb information, explains how he watched many people try to effectively describe and solve a ‘wicked problem’, such as the best way to make toast.

What was the most effective approach Wujec found? Getting people with a range of skills to work together with post-it notes and paper to perfect the workflow. Interestingly he suggests it is even more effective when they work silently.

MOOC design

This struck a chord with us as we tend to work in similar ways when designing our MOOCs – though our team rarely work in silence (maybe something to try next time). We take cues from the JISC ViewPoints project and constructive alignment to plan and assemble each week of the course. With the academic team, we establish the audience, our motivations as well as those of the learners to clarify the aims and outcomes. We then use rolls of brown paper to create a course timeline, writing down what the learners must be able to do at the end of the course and for each week that they couldn’t do before they started. We ask how we/they will know they have attained this learning (some form of assessment in the loosest sense) and then plan activities and content that will get them to that point.

Post-it notes have the great advantage of being movable, whilst also allowing multiple people to contribute and collaborate on the whole. This is something Wikis aim to allow (though not always successfully). Started with pen and paper, rather than technology, helps us collectively produce something we can use very quickly and without many of the restrictions electronic tools tend to entail. As my colleague Nuala says, technology can get in the way at this stage.

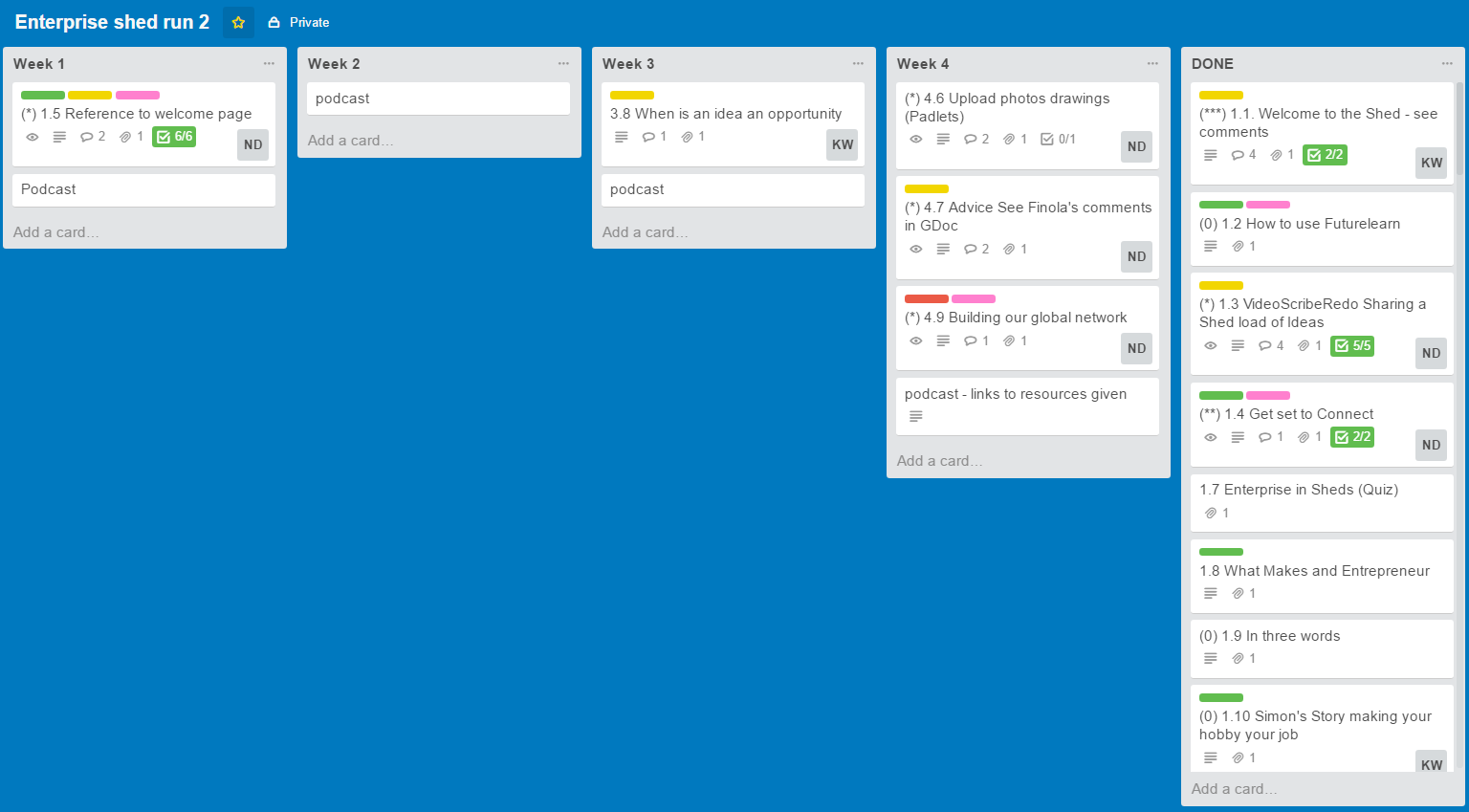

Once planned on paper, we have found that using Trello is a bit like using post-it notes online, but with added ‘to do list’ and project management functionality. After planning on paper and in Trello, we then create the shell of the course in the FutureLearn platform. This helps visualise and restructure further, before testing on willing guinea pigs, and changing the design again. The bits we change and iterate the most tend to be the highest quality and most positively received elements of our courses.

MOOCs and collaboration

MOOCs themselves can become great collaborative spaces. We had many wonderful contributions from learners on our courses. For The Enterprise Shed, this was one of the lead-educator Katie Wray’s aims. The whole course was a bit like a World Cafe. We did as much as we could with the tools available to aid collaboration. We crowd-sourced ideas links and videos (including favourite TED talks such as the one at the start of this post) . Learners also shared designs through Padlet, another free collaborative technology which is a bit like paper and post-it notes. This is a great tool for sharing, but it could do with a commenting feature to facilitate feedback on posts.

Learners were able to gave each other feedback on ideas through comments in discussion and through the peer review tool in the platform.This was a really valuable element of the course, and something we would like to do more of.

Making MOOCs more collaborative

One of the tension for us with our courses at present is that the busier they are (the more active users) the harder it is to track what is going on in discussion boards, both for us and for the learners. It would be great if learners could tag posts so that people could find like-minded people and relevant posts more easily.

Small group discussions are coming in FutureLearn, but it will be wonderful if tools within MOOCs could be developed to aid the formation of groups around shared interests. Better still if we could have tools to collaborate in a way more like being in a room with paper and post it notes. We could really make a virtue of the Massive in MOOCs if we had these tools.

![NUTELA Peer Recognition Award winner Gigi Herbert [Right] with Salome Bolton, who nominated her.](https://blogs.ncl.ac.uk/ltdev/files/2015/06/Salome-and-Gigi-300x225.jpg)