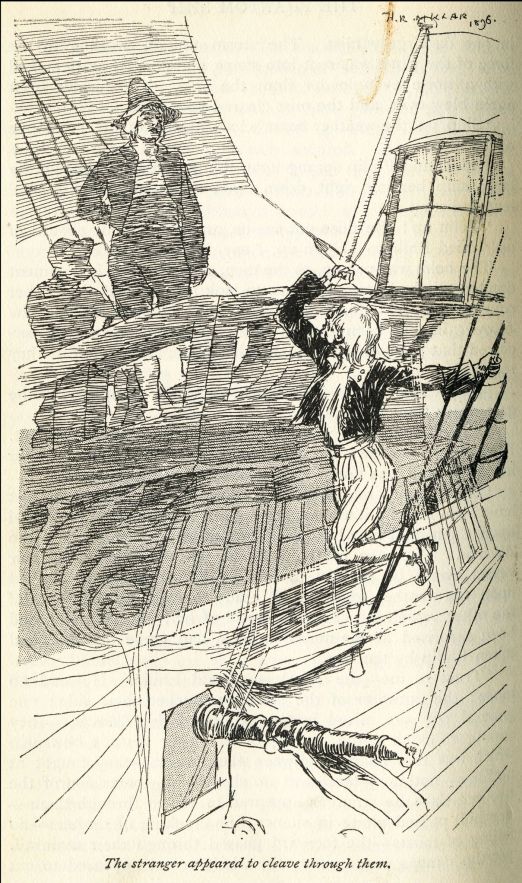

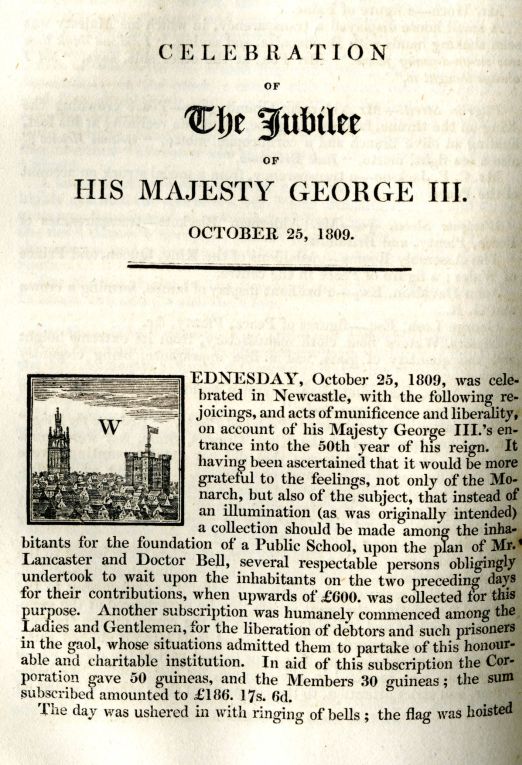

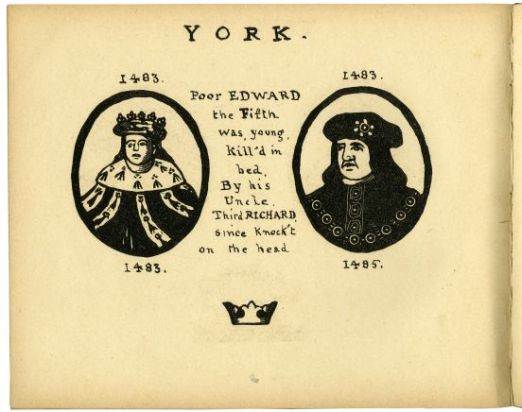

Joseph Crawhall II (1821-1896) revived the chapbook tradition. Several Sovereigns for a Shilling (1886) is a collection of lithographed portraits of monarchs, alongside irreverent rhymes – quite typical of Crawhall’s humour.

On 4th February 2013 archaeological experts from the University of Leicester announced to the world that “beyond reasonable doubt” they had uncovered the bones of Richard III. Richard was 32 years old when he was killed at the Battle of Bosworth Field in 1485 by the forces of Henry VII. As this verse from Joseph Crawhall describes, Richard was “knock’t on the head” and the skeleton bears evidence of eight injuries to the skull. He was the last English king to die in battle and with his death came the end of the Plantagenet dynasty, giving rise to the House of Tudor.

The skeleton also provides evidence of scoliosis – a curvature of the spine – but no hunched back or withered arm as William Shakespeare and Tudor historians like Thomas More would have you believe.

Richard was born at Fotheringhay Castle in Northamptonshire but spent many of his formative years at Middleham Castle in Wensleydale and it was in the North of England, as President of the Council of the North, that he earned respect as a protector against the Scottish raids and as a just keeper of the peace.

On the death of their father in 1461, Richard’s brother became Edward IV and created Richard Duke of Gloucester. When Richard’s brother, Edward IV died, Richard was made protector of his two young nephews: Edward and Richard. Accusations of illegitimacy mounted against the boys and Richard III was crowned King in July 1483 whilst the boys, who had been lodged in the Tower of London, mysteriously vanished. Rumour would have us believe that Richard murdered the princes: “Poor Edward the fifth was, young, kill’d in bed, By his Uncle, Third Richard”, as Crawhall puts it.

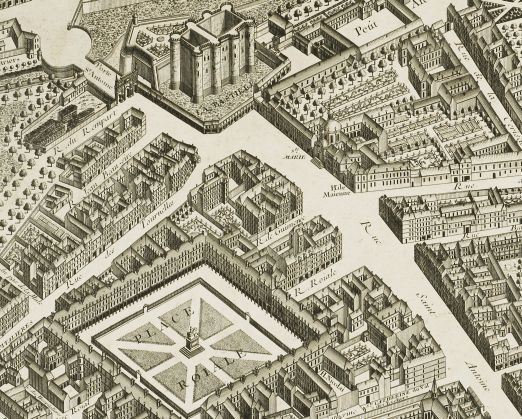

Richard was said to have been buried under the choir of Greyfriar’s Church in Leicester but the building had been demolished in the 16th Century. It was by analysing maps that the location of the church was identified, where a car park stands today. Descendants of Richard, who provided DNA samples for comparison, were traced using historic records and documents. This demonstrates the continued relevance of primary sources and other historic materials.

Whether you admire Richard as a brave military leader (he remained on the battlefield while several of his men defected) and the person who introduced an early form of legal aid (the Court of Requests), or whether you believe the Tudor propaganda, it must be remembered that the period of the Wars of the Roses was particularly brutal and that people were governed by a different moral code. Richard’s Council of the North improved economic conditions in the North and he also banned restrictions on the printing and sale of books.

Richard will be reinterred in Leicester Cathedral.

If you are interested in reading contemporary accounts of Richard and this period, you might refer to the Paston Letters (White (Robert) Collection, W942.04 PAS) and to the account by Robert Fabyan, both of which are held in Newcastle University Library’s Special Collections.