Pybus Collection: Pyb C.v.5

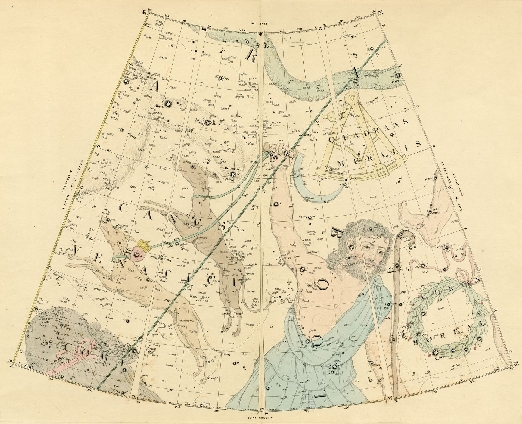

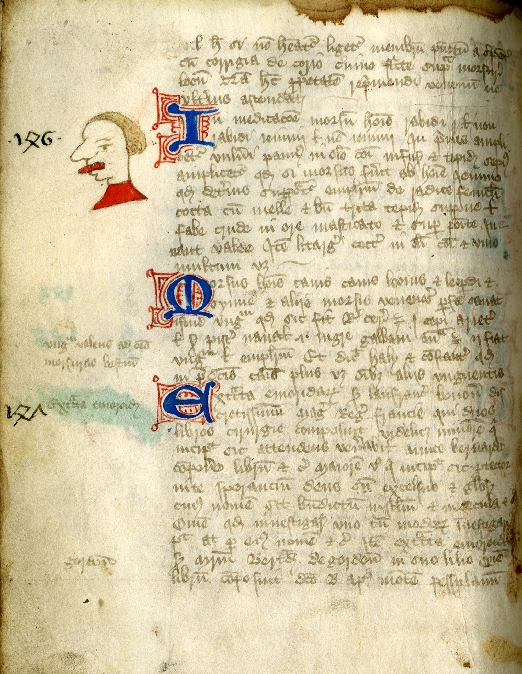

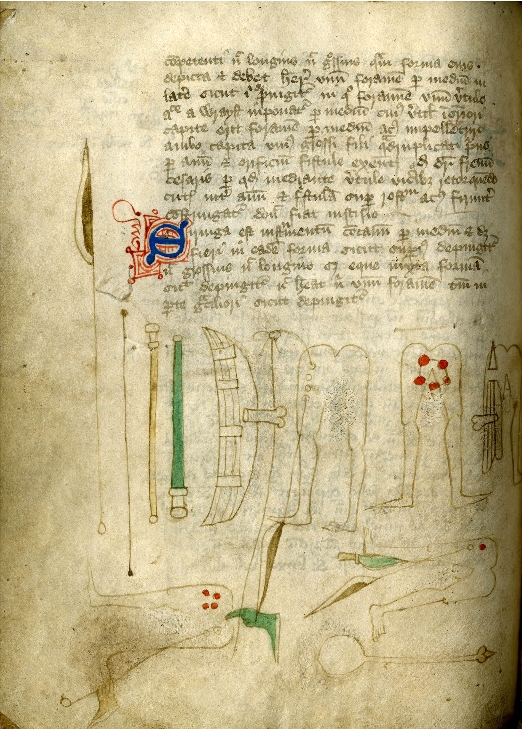

John Arderne (1307-1380) practised as a surgeon in Newark and London and earned himself great renown particularly for his medical works, written in Latin despite his lack of a university education. Arderne was typical of medical practitioners in the Fourteenth Century – embracing medical advances, pioneering new methods and referencing the likes of Hippocrates, Galen and Avicenna yet harking back to the Anglo-Saxons’ astrological approaches to medicine.

Arderne’s manuscripts were commonly illustrated, both to show techniques and remedies, and to aid the reader in navigating a potentially confusing text. This manuscript, written in Latin but including some passages in French near the beginning, has been illustrated with pictures of operations, instruments, plants, blazons, &c.

The manuscript was formerly part of the private collection of Professor Pybus (1883-1975) who donated his history of medicine books, engravings, portraits, busts, bleeding bowls and research notes to the University Library in 1965. The manuscript now bears his presentation bookplate but there is further evidence of provenance: it has been inscribed by W. Harrysson, Silvester Rowlestone, Sarah Ridall, Mary [Riddall?], Richard Pearson, Mster [sic] Rutter and Christopher Wainman.

Roughly contemporaneous with Arderne’ manuscripts, is Chaucer’ Canterbury Tales, the Prologue of which contains the following depiction of a physician grounded in astronomy, led by ancient classical texts, dressed in taffeta and silk, with a penchant for gold:

With us ther was a Doctour of Phisike;

Extract from The Poetical Works of Geoff. Chaucer …

In all this world ne was ther non him like

To speke of phisike and of surgerie,

For he was grounded in astronomie.

He kept his patient a ful gret del

In houres by his magike naturel:

Wel coude he fortunen the ascendant

Of his images for his patient.

He knew the cause of every maladie,

Were it of cold, or hote, or moist, or drie,

And wher engendred, and of what humour:

He was a veray parfite practisour.

The cause yknowe, and of his harm the rote,

Anon he gave to the sike man his bote.

Ful redy hadde he his apothecaries

To send him dragges and his lettuaries,

For eche of hem made other for to winne:

His friendship n’s not newe to beginner.

Wewl knew he the old Esculapius,

And Dioscorides and eke Rufus,

Old Hippocras, Hali, and Gallien,

Serapion, Rafis, and Avicen,

Averrois, Damascene, and Constantin,

Bernard, and Gatisden, and Gilbertin.

Of his diete mesurable was he,

For it was of no superfluitee,

But of gret nourishing, and digestible:

His studie was but little on the Bible.

In sanguine and in perse he clad was alle

Lined with taffeta and with sendalle.

And yet he was but esy of dispence;

He kepte that he wan in the pestilence;

For gold in phisike is a cordial,

Therfore he loved gold in special.

(Edinburgh: At the Apollo Press by the Martins, 1782) Vol. 1.

(White (Robert) Collection W821.17 CHA)