As EPSRC publishes their findings on gender perspectives within their research funding portfolio, our Centre Director, Dr Sara Walker and Centre Manager, Laura Brown discuss the challenges women working to help rebalance the mismatch face.

About the authors: Dr Sara Walker

Dr Sara Walker is Director of the EPSRC National Centre for Energy Systems Integration, Director of the Newcastle University Centre for Energy and Reader of Energy in the University’s School of Engineering. Her research is on energy efficiency and renewable energy at building scale.

About the authors: Laura Brown

Laura is the Centre Manager, EPSRC National Centre for Energy Systems Integration and Energy Research Programme Manager, Newcastle University. Her research tackles the challenges of integration of state-of-the-art thinking and technology into legacy energy systems.

As an academic team, we have a responsibility to consider Equality, Diversity and Inclusion in the way we conduct our teaching, research and knowledge exchange. Doing the right thing is not always easy. We are in no way experts. But surely it is better to try, and accept that we will sometimes get it wrong?

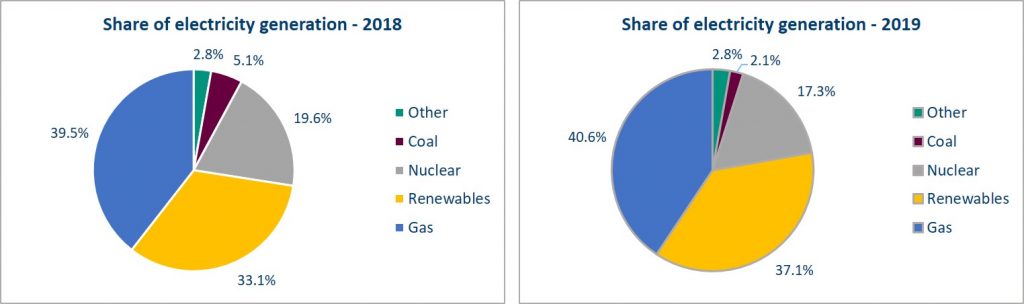

Our research is funded by the EPSRC, for the National Centre for Energy Systems Integration and the Supergen Energy Networks Hub. So, we were interested to read the recently published EPSRC report Understanding our portfolio: A gender perspective.

Within their report they state, “Underrepresentation of women in the engineering and physical sciences remains one of EPSRC’s largest equality, diversity and inclusion (ED&I) challenges and is a well-known issue in the engineering and physical sciences community.” We applaud the transparency that EPSRC has shown in issuing the report as we know, as scientists and engineers, one of the best ways of tackling problems is by considering the underlying data.

In our opinion, the findings of the report can be considered both worrying and illuminating. For example, higher value awards show significantly lower award rates to female Principal Investigators. Since 2007, applications of value over £10million have been received from 5 females, compared to 80 males. In 2018-19 (the latest year we have data for), just 15% of applications received were from female Principal Investigators.

Factors affecting application rates by female academics are likely to be numerous and complex, affecting individuals in different ways.

Some of these could be:

- Women win fewer scientific prizes and so the public see fewer “success stories” of women, discouraging women to take up science subjects. (Callier, Conversation, Jan 2019)

- Women are evaluated by their students as less effective teachers than male counterparts, which may impact career progression (Basow, JEP, Sep 1987)

- Women are less likely to be selected at application stage for things like access to equipment. This was noted in a study of Hubble telescope time , for example. ( Johnson & Kirk, HBR, Mar 2020)

- Women get paid less: “The EPSRC’s analysis of the salaries which applicants request on grants is a very effective illustration of the gender pay gap. Using age as a proxy for career stage, we see men get paid more than women at similar career stages, and this effect increases with seniority level.” From @TIGERinSTEMM

- The large grant applications are required to come from the Research PVC, of which we have very few women (Donald, Blog, Oct 2020)

- Women undertake more unpaid work than male counterparts as parents, carers and in household duties, and this impacts the time available for, and consequent success in, delivery of those measures of “success” which are valued for promotion in the workplace. This impact of unpaid work has been particularly marked during COVID lockdown for women in academia ( Gewin, Nature, Jul 2020) and (Pinho-Gomes, BMJ GH Vol 5 Iss 7)

We underline could in the above section, because there is simply a lack of data. Reading “Invisible Women” by Caroline Criado Perez (Vintage, ISBN: 9781784706289) makes you realise that “lack of data in academia” can be replaced with “lack of data in society”.

Data is not available from EPSRC for other protected characteristics, and so our understanding of the academic experience is often limited to our own lived experience. In order to address EDI in our institutions, we often ask those in the protected characteristic groups to represent a heterogeneous mix of people and experience. As two white women we bring our white privilege to the table (a great resource on this is here: https://www.racialequitytools.org/resourcefiles/mcintosh.pdf). Even within white privilege there are intersections with our Northern and Scottish roots, and class, for example.

McIntosh (1989) lists several white privileges, and given recent discussions in the UK of decolonisation of the curriculum and the during the current Black History Month, this one gives pause:

“When I am told about our national heritage or about “civilization”, I am shown that people of my color made it what it is.”

McIntosh (1989) White Privilege: Unpacking the Invisible Knapsack

We are more than white women. We are white, heterosexual, married women who have children. So, as EDI champions, how can we reflect the experience of the full diversity of women? Women of colour, women without children, women who are disabled, women who are homosexual, or people who do not associate with binary expressions of gender? We may be very close to women with different lived experiences and have an appreciation of their experience through family and friends for example. And what role for men, how can they better understand the lived experiences of the full diversity of men? How can our research teams become better environments for all, regardless of difference?

We conclude it behoves each of us to read, observe and educate ourselves about the experiences of others. Be a good example. To take responsibility for our own awareness, to be reflective, and commit to being a better global citizen. To be kind. To be human.