About the Author:

Dr Susan Claire Scholes is a post-doctoral researcher within the School of Engineering. Susan’s current research is in the field of whole systems energy research, working with the Supergen Energy Networks Hub at Newcastle University.

Previous research interests were in bioengineering where Susan was responsible for the investigation of explanted metal-on-metal hip prostheses and explanted knee prostheses.

Matlab and the GB Network System

Let me tell you a story…. It feels like it started a long, long time ago but in reality it has only been 20 months (this may still seem like a long time to some, depending on your age!). Twenty months of hard work but important work. This is when I started working on a model of the GB network system. This model already existed [1, 2] but it needed some work to be done on it to allow it to perform the tasks that I required.

Now, I had minimal experience (or knowledge) on Matlab but I am always eager to learn so I saw this as an opportunity to develop my research skills even further (I’ve been working in academic research for 21 years now, so it’s never too late to learn!).

I familiarised myself with Matlab and the model so I understood the background to my project; and this understanding developed as the time progressed. The adjustments needed on the model were only small; small in capacity but mammoth in the necessary effort to succeed!

The cost functions of each generation type in the GB network model were already in the model but they were just given as merit order equations; this was so the model was able to calculate the proportion of expected generation from each type of generation provider (wind, gas, coal, nuclear and hydro). But I needed it to calculate the true costs.

I knew this wouldn’t be easy, or quick! As a modeller, it is important to analyse results obtained and question their validity; you need to have confidence in the results that your model provides. It is essential that you compare your results with appropriate published data and relevant work done by others.

Using known data from previous years I was able to identify when the results from my model were not as good as they needed to be; and it allowed me to gain confidence in my work as it developed. This was an iterative process that required many hours of hard and repetitive work.

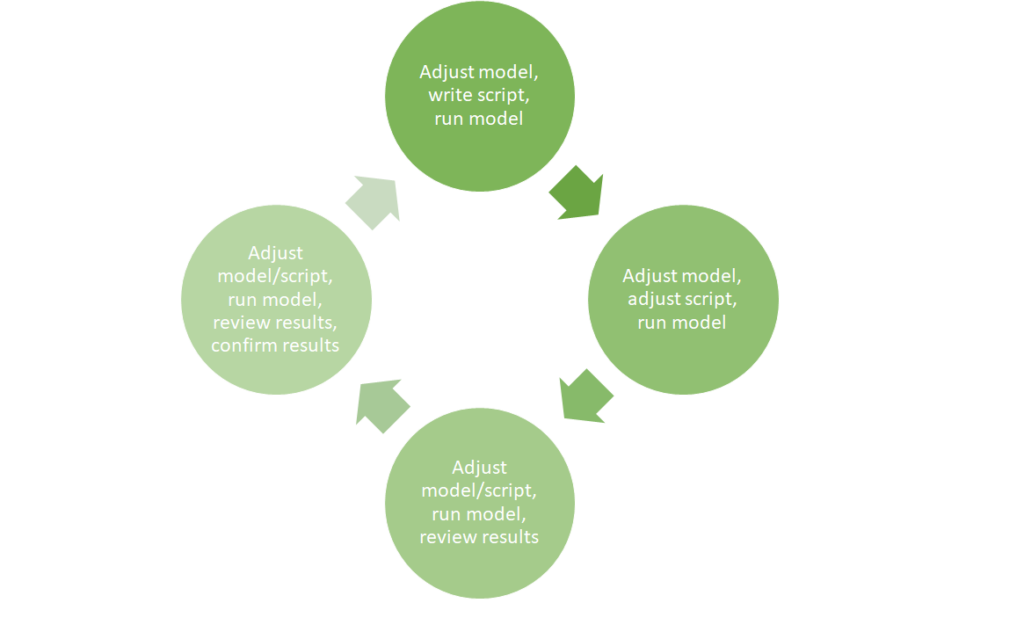

To get this done well it required a lot of effort and determination (and a few handkerchiefs to mop up the inevitable tears of frustration!). For months I was stuck in what seemed to be a never-ending loop:

- adjust the model, write the script, run the model – no joy

- adjust the model, adjust the script, run the model – it works!, review the results

- adjust the model/script, run the model – it works (but sometimes it didn’t!), review the results

- adjust the model/script, run the model – it works!, review the results, confirm results, add results to paper, find some new information

- adjust the model/script, run the model – it works!, review the results, confirm results, add results to paper, find some new information

- again, again and again until…

- adjust the model/script, run the model – it works!, review the results, confirm results, write the paper (with confidence that the model used is the most appropriate and performs the task well) and submit!

So, what have I learned during this time? Perseverance is key, determination is needed and patience would have been a bonus but I’ve always lacked in that! Unexpected things, like the University’s cyber security attack, and even a pandemic, can be obstacles but with the correct support they are not insurmountable. I also needed to learn that all models have their limitations.

You can minimise these limitations to produce the best model for your purpose but your model cannot do all, it will not be suitable for everything. Spend time on the model, like I say, for it to produce relevant results for your work but understand that there will always be limitations as to what the model can do.

As long as you are aware of these and you are able to explain the limitations imposed on your work (and why these are acceptable) then you should feel proud. Proud of the valid, valuable work you have achieved and the advancements you have made in your field of research. It was all worth it in the end!

References

- Bell, K.R.W. and A.N.D. Tleis. Test system requirements for modelling future power systems. in IEEE PES General Meeting. 2010.

- Asvapoositkul, S. and R. Preece. Analysis of the variables influencing inter-area oscillations in the future Great Britain power system. in 15th IET International Conference on AC and DC Power Transmission (ACDC 2019). 2019.