About the Author:

Professor Sara Walker is the Director of The Centre for Energy, in the School of Engineering. Her research focusses on renewable energy and energy efficiency in buildings, energy policy, energy resilience, and whole energy systems.

Sara is Director of the EPSRC National Centre for Energy Systems Integration, Deputy Director of the EPSRC Supergen Energy Networks Hub, and Deputy Research Director of the Active Building Centre.

My journey to professorship – struggles and triumphs

In November of 2021 I was promoted to Professor of Energy at Newcastle University. This has felt like such a career landmark for me.

I was brought up by my parents in Cramlington, a town to the north of Newcastle. When I was young my father was made redundant and the family moved into council housing. I never considered myself as poor, but I do remember we grew potatoes in the garden to save on food shopping and me and my younger sister would wear hand-me-down clothes. My older sister left school at 16 and got a job working in hospitality, and as my parents’ financial situation improved they were able to purchase their council house, but we were by no means affluent! At 15 I got a Saturday job at Whitley Bay ice rink in the cafeteria, and I started to earn my own money which was very empowering.

When I went to university at Leicester I noticed that my financial situation wasn’t the same as others around me. I had a grant from the council to cover most of my living costs and my parents also contributed to top my grant up. I got a part time job working at the bar in the students union, and also worked part time in a local pub. During summer vacations I always worked, normally bar work.

I remember waiting to use the public telephone one weekend to chat to my parents whilst at university, and watching the person on the phone in front of me crying crocodile tears to her dad. She needed money to buy a ball gown since it wasn’t fair for her to be expected to wear her existing ball gown that she’d already worn.

That’s when it really struck me that some of my fellow students were really well off! I didn’t join expensive societies like skiing and horse riding, I didn’t go to lots of balls and social events. For my graduation ball I hired my dress.

When I finished my undergraduate course in physics I was offered a PhD by my personal tutor at the university. I didn’t really know what a PhD was, I had been first in my family to go to university, and I turned it down. Instead, I did a teacher training course and got a job as teacher. After teaching for a short while I decided to go back to university to do a masters course in environmental science, because I had got really interested in energy issues through voluntary work. This led onto a research job, and an opportunity to complete a PhD part time whilst working as a researcher. I think this is the only way I could have completed a PhD since I didn’t have the financial resources to support myself on a student bursary. The part time PhD took five years whilst I worked as researcher and during that time I had my son Toby.

My early experience of academia was still affected by my background somewhat. I had to think carefully about attending academic conferences, because I didn’t know how long it would take for my expenses to be paid back. One time an expensive overseas trip wasn’t paid in time before I had to pay the credit card bill, and I could only pay the minimum and incurred interest, something I couldn’t claim back from my employer. Conference dinners were a minefield, I didn’t have lots of spare cash to spend on cocktail dresses. Even work suits were often bought from the catalogue and paid for monthly when I first started out. Later in my career, financially and socially I found myself excluded from social events and the associated networking opportunities of corporate boxes at football, or golf at exclusive members courses.

Academic statistics do not portray the full picture…

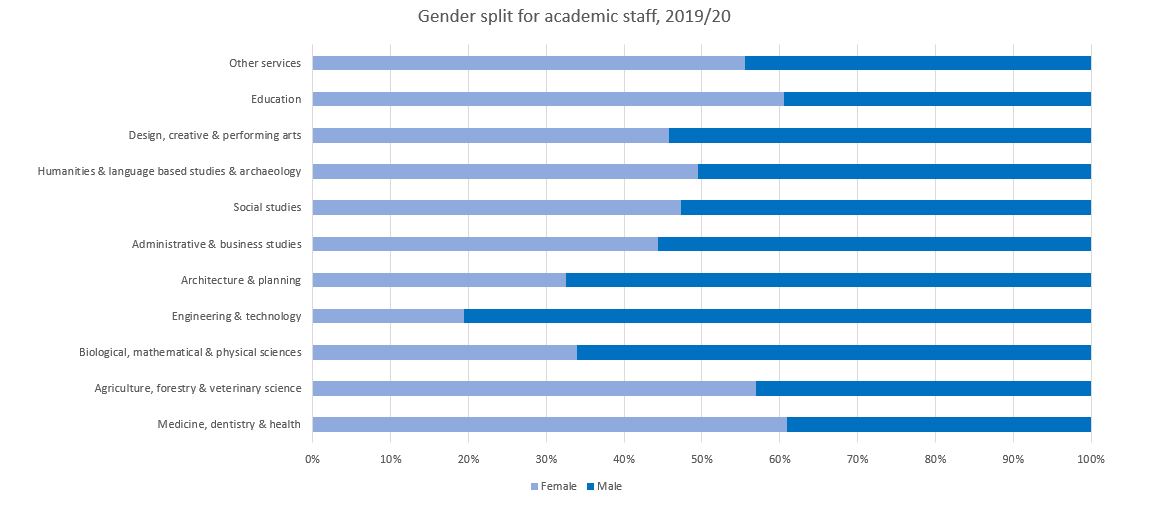

HESA statistics are available, to tell us something of the makeup of our UK professoriate. In 2019/20 there were 22,810 professors, of which 6,345 are “female”, 16,415 “male” and 50 “other” gender. Of the 21,055 professors with known ethnicity, 2,285 are BME. 735 professors are known to have a disability. Looking just at engineering, this discipline areas has the lowest proportion of female academics (see figure below). There are no statistics for socio-economic group, and no statistics for intersectionality (i.e. we don’t know how many BME are female, or how many BME have a disability, for example). There are also statistics for grant applications and success from EPSRC, by gender. Data for other protected characteristics are lacking.

Source: Departmental demographics of academic staff

Source: EPSRC Understanding our Portfolio

I am acutely aware of the lack of role models in academia from lower socio-economic backgrounds. But there are also a lack of role models who are LGBTQ+, minority ethnic, disabled, non-white, from different faiths, or any combination of these. In seeking out these role models, we expect people to be open about their protected characteristics, regardless of the discrimination this may attract.

Moving forward…

Raising up colleagues, giving equality of opportunity, and being more aware of the potential barriers to engagement, are approaches we are taking at Newcastle University’s Centre for Energy. For example, we are working hard to encourage involvement from all job families in the Centre for Energy – research as an activity spans so many jobs including project managers, technicians, finance, research students, research staff and academic staff, for example. We want the Centre itself to address issues of fairness and equity in energy research, and so we have a theme on Justice, Governance and Ethics. We are tackling global issues of energy transition, issues which need a range of perspectives across gender, race, (dis)ability, sexual orientation and religion in order to come up with solutions that work for the majority, and not the select few.

I have a strong northern accent, and am proud of my roots and to be back in the north east working at a Russell Group university. But I am still that kid from the council estate. And I am proud of that too.