Lauren Aspery

It’s that time of year again, and nothing says Christmas like the scatological humour of children’s author and illustrator, Nicholas Allan. I was fortunate enough to spend a day at Seven Stories rummaging through his uncatalogued Christmas archive last Winter, and one year later I thought I’d take the opportunity to share what I found.

If you don’t know Nicholas Allan, he is best known for his toilet-tastic titles including The Queen’s Knickers, The Giant’s Loo Roll, Cinderella’s Bum, The Royal Nappy, as well as his more festive work, like Jesus’ Christmas Party, Father Christmas Needs a Wee and Father Christmas Comes up Trumps. Having been fortunate enough to vicariously enjoy these books via a younger sibling, I was absolutely thrilled to learn I could put them to use for an undergraduate assignment on Lucy Pearson’s Children’s Literature Module, ‘Home, Heritage, History’. In fact, I ended up enjoying my day at the archive so much, that I ended up sticking around to do an MLitt!

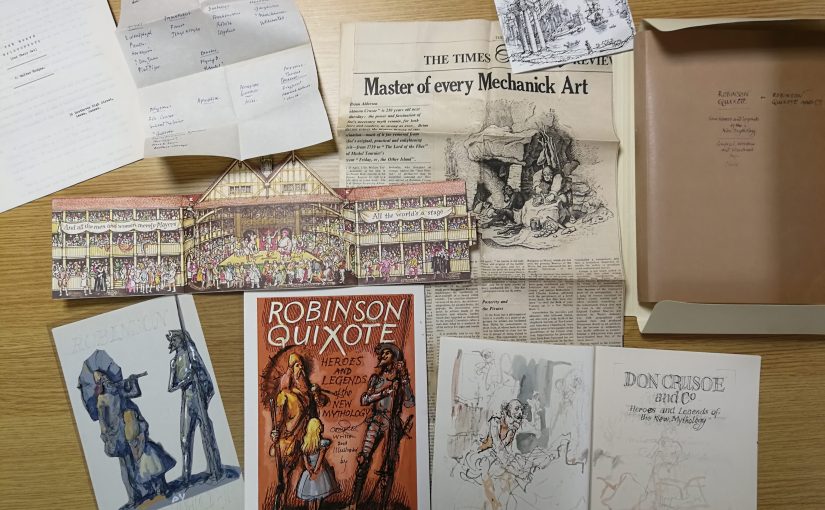

This was my first time visiting the Seven Stories Felling site, and was a perfect way to get me into the Christmas spirit. I was greeted by Paula Wride, who showed me the ins and outs of the archive before setting me up with my work – although I’d hardly call it work, it was like Christmas came early!

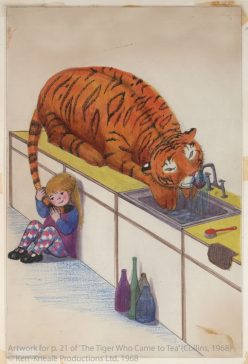

The first item I came across was a hand-painted mother’s day card signed by Allan, which features an image of Mary holding Jesus in the same style as the illustrations for Jesus’ Christmas Party. There’s no way of knowing which came first – the card or the illustrations for the story – but I’d like to think this is what inspired him. I was also surprised to see so many different cover designs for Jesus’ Christmas Party with such vast differences, including the version I have on my shelf at home. Some featured angels, some included the whole nativity and some even had the titles in different languages as well! There was even his final watercolour artwork for the figures later produced for the accompanying activity playset and designs for the cover of, what has now become, Jesus’ Christmas Party: The Musical! Here are some of the covers in circulation now, the middle being the most recent:

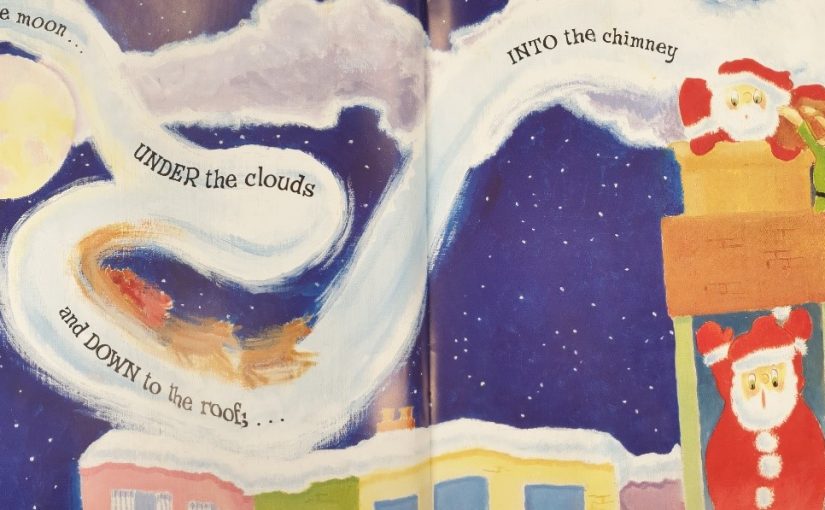

The image at the top of this article is, perhaps, my favourite painting by Allan. The final print of Father Christmas Comes up Trumps does not do justice to the original version I was fortunate enough to see. I was blown away by the vibrance of the colours against what ended up on the page, but what was even more surprising, is that a coffee stain in the clouds (top left of the second page if you look carefully) made it to the final text. I’ve since wondered whether the editor missed it, or if the picture was just too good to waste!

I couldn’t believe the intricacy of some of Allan’s drawings. The files were filled with tiny scraps of paper with detailed miscellaneous final artwork the size of a penny. There were bells, holly, gifts, and even a specific gift design for the Father Christmas Needs A Wee barcode! It’s clearly a lot of work being both an author and illustrator, but seems like a lot of fun to have so much input in your work.

Of course, the Seven Stories Archive is not just home to Christmas picturebooks, but is brimming with exciting resources all year round. With that said, I don’t think any Christmas will compare to seeing Allan’s watercolours of Father Christmas breaking wind in various locations.

It seems only natural to conclude by quoting the final pages of Father Christmas Comes up Trumps:

‘So the world wakes up, And the children all cheer…

Father Christmas has come up trumps, Now it’s the BEST day of the year!’

Nicholas Allan, Father Christmas Comes Up Trumps (2013)

Merry Christmas from all of the Children’s Literature Unit here at Newcastle University!

Book cover images courtesy of goodreads.com