The Children’s Literature Unit has a close working partnership with Seven Stories: The National Centre for Children’s Books, an organisation committed to fostering academic research into its archive. As well as working with Newcastle University, Seven Stories also has a strategic partnership with Northern Bridge, the Arts and Humanities Research Council consortium of universities in the North East and Northern Ireland. This partnership connects doctoral researchers with the Seven Stories collections. Here, Durham University PhD candidate Antonia Perna talks about her Northern Bridge placement at Seven Stories.

The purpose of Northern Bridge placements is to provide PhD students with opportunities for professional development outside the academy, to develop new skills and to apply our academic skills in a new setting. From March to May 2019, I undertook a placement at Seven Stories, where I worked on cataloguing the Laura Cecil collection. My own research focuses on childhood in Revolutionary France, and I explore in particular how schoolbooks and children’s literature versed young French people in republican politics and civic conduct. In this way, I have worked with children’s literature for my academic work, and this is what sparked my interest in Seven Stories. However, although there is some foreign-language material at Seven Stories, most of the collection is in English, pertaining to British children’s books, and dates from the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. I was intrigued to learn more about such books, and also to find out what an archive looks like from the other side.

Most academics in the arts and humanities have at least some experience of working with archival material, and we all know how much difference a comprehensive catalogue can make! Cataloguing the Laura Cecil Collection at Seven Stories has given me a window onto the process of compiling a catalogue, and insight into the kinds of considerations a cataloguer is faced with—and thus into what happens before a researcher opens the catalogue.

The Laura Cecil Collection contains over forty boxes of material from Cecil’s career as a literary agent. The first agent to specialise in children’s literature, Cecil worked with several well-known children’s authors and illustrators, including Robert Westall, Diana Wynne Jones and Edward Ardizzone. Upon her retirement in 2017, she donated her files to Seven Stories; they consist primarily of correspondence with and relating to her clients, c. 1970-2009.

Having been instructed to provide a description for each file, I was faced with the challenge of deciding what information to include. How do you decide what is significant, in a file that could contain any number of documents? How do you predict what might be pertinent to a research project that is, as yet, hypothetical? After an overview of each file, I selected letters and documents of note according to how they were distinct from others in the file, or how they contribute to our understanding of a particular book, perhaps in terms of its editorial process or reception. When uploading this to the catalogue, I also cross-referenced related documents in other Seven Stories collections to aid research across the archive. As an academic, my instinct was to address all possible lines of enquiry that the documents could be used for; I had to accept, however, that I could not anticipate every possible research project.

Similarly, as a researcher, I was drawn to arrange material in a logical order, to facilitate locating and retrieving files. Specifically as a historian, however, I wanted to maintain the files’ original order, as this is part of the collection’s history. Generally, it is considered good archival practice to maintain the original arrangement and structure of a collection, and so I tried to respect this. Where I could not discern any order to the arrangement of files, I highlighted this in the catalogue, and, in the case of the Robert Westall correspondence, I did re-arrange files chronologically. The pressure to make the right decision here, and not to make a mistake that was irreversible, was rather daunting. Although I had worked with archival material many times in my academic work, I had never given much thought to how material was arranged, and suddenly I felt an overwhelming responsibility to get it right! I hope I did!

Another challenge I faced was the need to remain impartial. Of course most academics try to write in an objective tone most of the time, but we nevertheless analyse and interpret our sources, working them into an intellectual argument. As a cataloguer, my task was simply to report what was in the box. I could try to anticipate and respond to academic enquiries to an extent, but I could not pursue them, nor could I make emotional or moral judgements on the material. Having read five years’ regular, amicable correspondence between Laura Cecil and Robert Westall, I felt some shock at Westall’s sudden death (in 1993), and I held back empathetic tears as I wrote, simply, ‘notable documents include… a note with costs for his memorial service (manuscript)’. The cataloguer sees and knows every document in a file; she observes and records, but her tone must remain detached.

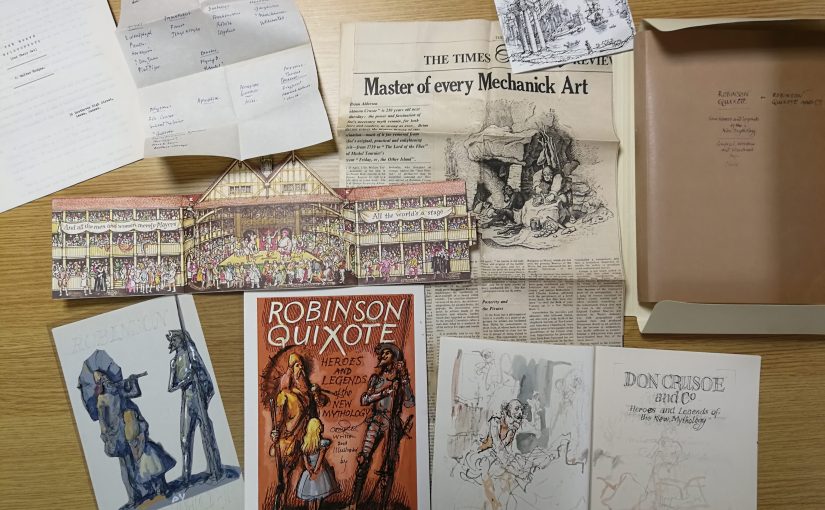

Nevertheless, getting to know a collection can be an exciting process—not least because some boxes contain hidden treasures! For instance, I was fascinated to discover a mock-up for an unpublished book by C. Walter Hodges, with original artwork, and to see how Sarah Garland illustrated her letters to Laura Cecil. On the other hand, there can be disappointments too. After half an hour engrossed in a draft of Robert Westall’s novella, The Duplicator, I was left with a cliff-hanger when I realised the text was unfinished! I have since emphasised in the catalogue that this story is both unpublished and unfinished, so that researchers will not make the same mistake!

After three months at Seven Stories, I would say that cataloguing a collection is something every academic should have a go at, if interested in archival research. My experience on this placement encouraged me to explore a collection as a whole, making links between individual documents, and to think more about the provenance of material. It also highlighted the value of an open-minded approach to research, where research questions may not yet be defined, and may be shaped by the material discovered. Of course, as academics, we know these things, but often practicalities and time constraints compel us to pre-select material and not to widen our parameters. Sometimes, though, the most useful document is in the box you might not have opened… Sometimes it might not be specifically highlighted in the catalogue—despite the cataloguer’s best efforts to predict your project!

Banner image: A selection of material by C. Walter Hodges, within the Laura Cecil Collection. LC/01/07/01. © Seven Stories: The National Centre for Children’s Books.