Silent Survival: Representations of Refugee Children’s Traumatic Separations

Dr Maria Chatzianastasi, Helen King and Lucy Stone

‘It feels a bit like the first day of school,’ Helen said as we made our way into the auditorium of Norra Latin, The Stockholm City Conference Centre, for the opening of the 24th Biennial Congress of the International Research Society for Children’s Literature (IRSCL) this summer. A fitting statement in more ways than one. Norra Latin, as we soon learned, is a former school.[1] The first time for Helen and Lucy, we were bundles of nerves, excitement and anticipation. We’d carefully selected our outfits, had our ‘school bags’ over our shoulders (we were issued with congress tote bags and Moomin characters notebooks) and compared timetables, the extensive congress programme.

There were many panels that applied the congress theme – Silence and Silencing in Children’s Literature – to readings of representations of child refugees in children’s and YA novels. One panel brought together Ruth Lowery who spoke on refugee children as agents of social change, Evelyn Arizpe who explored the empowering potential of refugee narratives for displaced children, and Michael Prusse who explored the problems in claiming to “give voice” to the refugee experience. In another panel on refugee picturebooks, Lesley Clement, Margaret Reynolds and Petros Panaou discussed the representative challenges posed by communicating the trauma of displacement in pictures. Pictorial representation of the refugee-migrant experience was also the focus on which Mavis Reimer, Karin Nykvist and Jaana Pesonen spoke.

One recurring question was about the voice of the child refugee: how can it be heard?; is there such a thing as an authentic voice, when often the experiences and trauma of refugees are absorbed by authors and/or illustrators with no direct experience of forced migration through “listening” to various sources such as others’ accounts, the media, and the arts?

In our panel, we proposed another kind of listening. Trauma theory has shown that silence can be a significant form of communication for those who have been subjected to traumatic experiences. We discussed texts in which children’s silence features as a response to separation, exile and refugeedom from different war zones and time periods, providing important insights into understanding refugeedom.

‘It’s wonderful to be a refugee’: the apparent optimism of Judith Kerr’s drawings made as a child exile from Nazi Germany

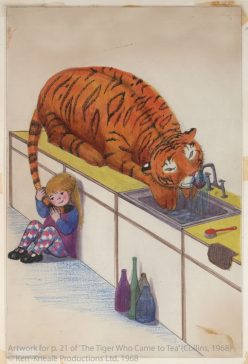

Our panel opened with Lucy’s paper ‘It’s wonderful to be a refugee’: the apparent optimism of Judith Kerr’s drawings made as a child exile from Nazi Germany.[2] In this paper, Lucy paid tribute to Judith Kerr, remarkable child artist and children’s author-illustrator, who sadly passed away in May. Lucy discussed two of the drawings ten-year-old Kerr made as a child in 1933 Switzerland, the first country in which the Kerr family sought refuge from Nazi Germany.

Their subjects – children dancing as they sing ‘Ring a Ring o’ Roses’ – is a ring game that has long been played across Europe. Peter and Iona Opie suggest that it is ‘almost a synonym for childhood’ (1985, 221). Here, it would seem a joyous, harmonious childhood. However, in this paper Lucy argued that reading these drawings in light of their biographical and historical contexts shows that the trauma of childhood exile that appears to be absent is in fact silently present. By reading the drawings in this way it becomes evident that Kerr was able to symbolically express some of the trauma she suffered as a consequence of the family’s forced migration from Nazi Germany, but also work through it and simultaneously develop drawings skills that she would employ in her illustrations as an adult. What also emerged over the course of this paper is the fact that child Kerr belonged to what Manon Pignot has termed a ‘graphic community’ (2019, 174) – children with experience of war, exile and/or persecution who draw, or drew. Reading Kerr’s drawings within this community helps illuminate her childhood creative practice. At the same time, Kerr has a unique position within this community. In studies of children’s war-time drawings, it is often the case that little is known about the children who created them. Moreover, frequently just a handful of drawings by each child is conserved. In the case of Judith Kerr, however, her archive at Seven Stories: The National Centre for Children’s Books spans from the pre- to post-exile years and holds many examples of juvenilia, making it possible to explore how a child refugee, with the opportunities to draw freely, was able to work through challenging exilic experiences.

“Have you ever listened to silence speaking?”: Trauma and survival in the Cypriot story “Maria of Silence” (1998).

“Have you ever heard Silence speaking? If you try to listen carefully, you will […] Sometimes, its words can reach the heart” (Charalambous, 1998: 37).

This is a challenging question, even a paradoxical one we may assume? And how could we listen to something which is not even there? How could we listen to an absence or maybe a gap, would be the next question. However, despite the paradox embedded in the narrator’s words in ‘Maria of Silence’, this quote carries a strong message about the powerful impact of silence; it encourages readers to listen to its words and try to understand and interpret it, but it also attests to the value of the words and stories found in small texts that are beyond our reach or knowledge.

Maria’s paper explored the significance of silence in Cypriot juvenile writing about trauma as experienced by some enclaved families who refused to leave their place of origin in the north after the events of 1974. Focusing on a particular example of writing, the paper set out to listen to and interpret the ways in which ‘silence’ is used to represent, register and express a quotidian form of trauma.

Agni Charalambous’ short story «Η Μαρία της σιωπής» [“Maria of Silence”] (1998) about enclavement creatively incorporates the “enigmatic relation between trauma and survival”: an expression used by Caruth based on Freud’s notions of trauma. According to Caruth, “for those who undergo trauma, it is not only the moment of the event, but […] survival itself […] can be a crisis (9). In the story crisis finds form in Maria’s prolonged silence from the moment she is violently separated from her family. Her trauma, however, remains permanent and so does her silence, to which Marilena, Maria’s friend, begins to listen. When she begins to understand and explore the possibilities of listening through silence Marilena addresses readers with the challenging question: “Have you ever heard Silence speaking?” (Charalambous 1998, 37). As the literary reading of the story began to listen to and unravel the literary uses of silence in the text, it also added to trauma theory. Rather than merely listening to what theory says and silently reproducing it, the discussion also listened to what theory does not say. In so doing, it spoke something to trauma theory and helped extend it.

As Maria’s paper has shown, the text is constructed around an aesthetics of silence, in which silence is used as a powerful literary device to represent the traumatic suffering arising from family separation and refugeedom as a result of the confining conditions of enclavement. It is first used as a symptom of trauma but also as a form of testimony that creates several layers of witnessing and allows readers to bear witness to another perspective of trauma associated with refugeedom. It points towards the power of silence over voice or words and encourages a critical form listening, one that respects the otherness of the traumatic experience and finally it poses questions and challenges a specific political situation.

Ultimately, as Maria concluded in this paper, Cypriot children’s literature is a body of literature with a wider theoretical importance as its study can reveal issues surrounding the experiences of refugees from another not widely known but nevertheless significant perspective that speaks to and addresses trauma theory.

“How could she ever put those terrible pictures into words?”: The paradox of silence in Beverley Naidoo’s The Other Side of Truth

In her paper, Helen explored silence as both a survival mechanism and a source of trauma for the child refugees in Beverley Naidoo’s The Other Side of Truth (2000). She explored the Naidoo archive held by Seven Stories, revealing something of the tug of war between speech and silence that is part of being a refugee child. The archive shows both how the bureaucracy of the UK asylum process perpetuates this traumatic silencing of the refugee child, and how the act of storytelling allows the child to recover some agency.

The Other Side of Truth tells the story of children Sade and Femi, who must flee Nigeria following their father’s criticism of the government and their mother’s subsequent murder. Using false passports and withholding their names and story from the UK authorities, the children’s silence can be read as a survival mechanism, a form of ‘micro-political resistance’ to the oppressive structures they find themselves within (Wagner 2012, 100). However, this silence also entails a form of secondary trauma for Sade: the injunction to lie undermines her moral code; her silence precludes her psychological healing, causing traumatic recurrence of the ‘terrible pictures’ of her mother’s death; the withholding of their story inhibits their father’s plea for asylum (Naidoo 2000, 51). This reveals the paradox of silence in Naidoo’s novel, in which the condition of refugeehood places the physical and psychological health of the child at odds.

The Naidoo archive holds paraphernalia from the UK immigration system, telling a depersonalised version of the story of seeking asylum, and indicating that the trauma experienced by refugees often has a social dimension. The story and subjectivity of an individual or family, in order to be processed through the immigration system, is reduced to a number, to a place in a queue, to the identifier of ‘a person who is liable to be detained.’ However, within this traumatic silencing the archive reveals the ‘possibility of testimony’ (Caruth 1991, 129). Naidoo encountered individual refugees during her research process, and their stories have informed the narrative as much as any of the official documents. That hearing individual stories was such an important part of the research is evident in Sade’s development, as she instigates social change by publicising her family’s story.

Although there were there were many voices discussing representations of child refugees, we did feel that at such a huge event these voices got a bit lost and didn’t talk to one another as productively as they could have. This led us to reflect that a symposium where this is sole theme, and it is possible to hear most of the papers and there is greater time for discussion and networking, would be a better forum to give this topic the depth of attention it deserves. But the size of the Congress was also an enormous positive, giving delegates the opportunity to attend panels on topics different from your own research areas and interests. Moreover, against the backdrop of Stockholm, the Congress was able to offer a rich cultural programme – highlights included a traditional Swedish Smorgasbord in the fairy tale-like Golden Hall of the Stockholm City Hall, a guided tour of Astrid Lindgren’s apartment and the Nordic children’s literature night at Junibacken, a children’s culture centre focusing on children’s literature.

*

Maria completed her doctoral thesis, Tracing and translating trauma: childhood, memory, and nationhood in Cypriot children’s literature since 1974, at Newcastle University in 2017 and she currently works as a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Nicosia. Helen is entering the second year of her doctoral project, an exploration of the representations of displaced children in Beverley Naidoo’s fiction and archive, with a view to developing public engagement work with Seven Stories using refugee narratives. You can learn more about Helen’s project on the Vital North blog. Lucy is writing up her thesis, a case study of the juvenilia children’s author-illustrators Judith Kerr (1923 – 2019) and Tomi Ungerer (1931 – 2019) made in exile in the Nazi era. You can see highlights of the Kerr archive in the digital exhibition Tiger, Mog and Pink Rabbit – A Judith Kerr Retrospective on the Seven Stories website and read about her project in an interview for tomiungerer.com.

We would like to thank our moderator Dr Tzina Kalogirou (National and Kapodistrian University of Athens), Dr Lucy Pearson, Professor Kim Reynolds and Dr Hazel Sheeky Bird for reviewing our draft papers, Kim and Dr Emily Murphy for being at our panel, Lucy for kindly promoting our panel via twitter and student members of CLUGG who provided invaluable feedback in the stage of composing our panel proposal last autumn. Emily gave an excellent paper on China and the Cosmopolitan Child in Elizabeth Foreman Lewis’s Young Fu of the Upper Yangtze (1932) and we extend congratulations to Kim for being awarded an Honorary Fellowship in recognition for her outstanding contribution to the IRSCL and field of children’s literature. These fellowships are awarded at each IRSCL Congress and a full list of recipients over the years is available on the IRSCL website.

Aesthetic and Pedagogic Entanglements, the 25th Biennial Congress, will be taking place in Santiago, Chile, 27 – 31 July, 2021. Information will be regularly updated on the IRSCL Congress 2021 website. You can read about the IRSCL and past 23rd Biennial elsewhere on the blog.

[1] Norra Latin is also the title of and setting for a YA novel by Sara Bergmark Elfgren. We had the chance to hear Sara speak about this novel at the theme night on Nordic children’s literature at Junibacken, a children’s cultural centre in Stockholm focusing on children’s literature. Unfortunately, Norra Latin isn’t yet translated into English.

[2] Kerr’s father, eminent writer Alfred Kerr, records this claim made by his 11-year-old daughter in his diary (1979, 26).