Elisa Marazzi

It is widely accepted that what we now call children’s books were born in the 18th century, when both the Enlightenment and commercial reasons made some farsighted men and women start publishing books that were explicitly addressed to children. But children existed also before the 18thcentury, so what did they read?

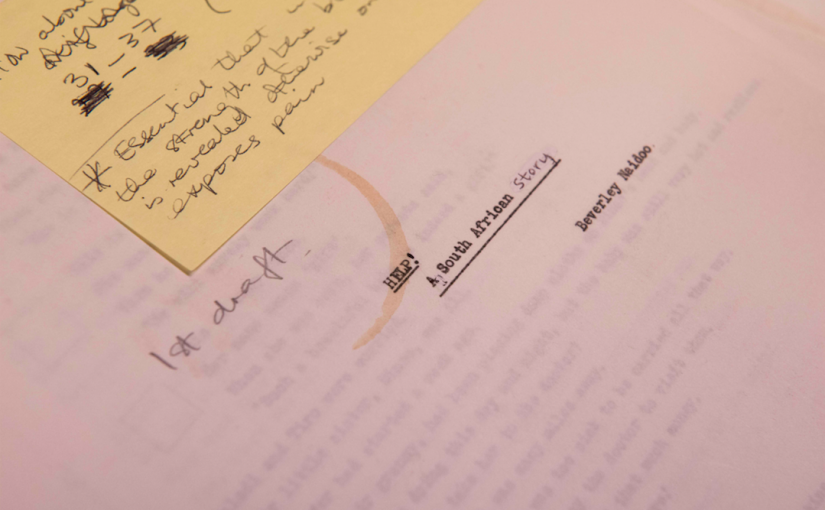

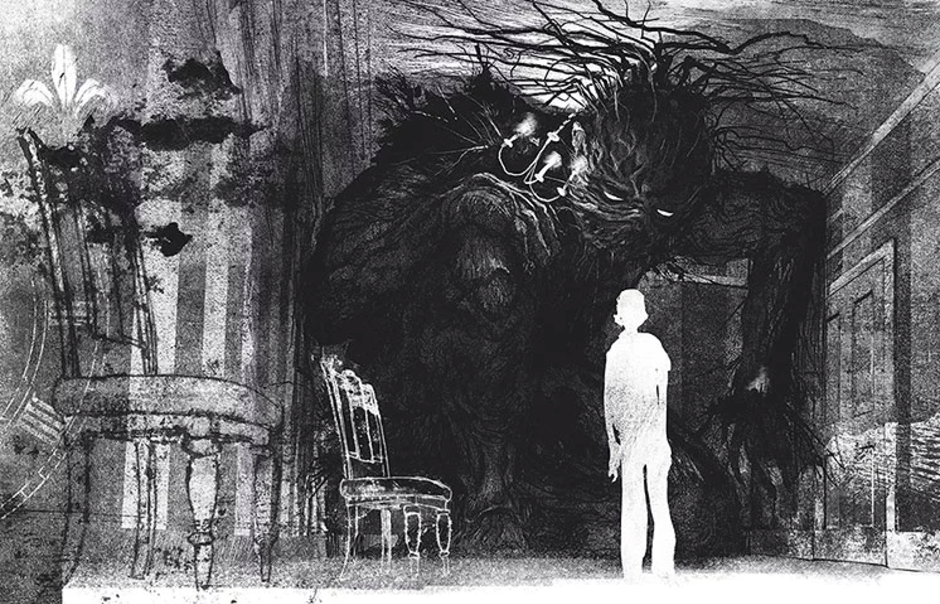

Some of them were so lucky that their parents or their preceptors commissioned, wrote, and even assembled books that were to be used exclusively by them. Let us think to the illuminated manuscript assembled for Claude of France in the early 16th century [picture 1], or to Fénelon’s Adventures of Telemachus, written in the 17th century for his pupil Duc de Bourgogne, second in line to the throne of France. Not to mention the nursery library assembled by Jane Johnson for her children in the early 18th century.

Many more children must have encountered the printed materials that circulated widely among peasants, working classes, servants, etc. since the invention of the printing press. In spite of the fact that literacy rates differed depending on urbanism, religion, emigration, and many other factors, it has been discovered that a great part of illiterate or semi-literate people not only had many opportunities to enjoy narrations by just listening to them, but were also keen on buying cheaply printed products even if they were not able to work them out completely. How about their children?

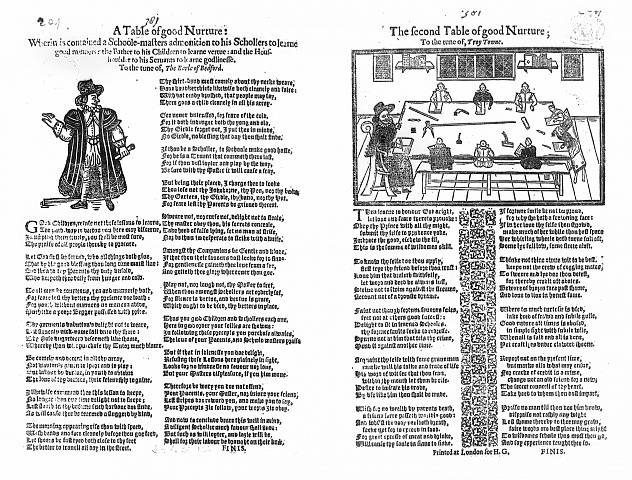

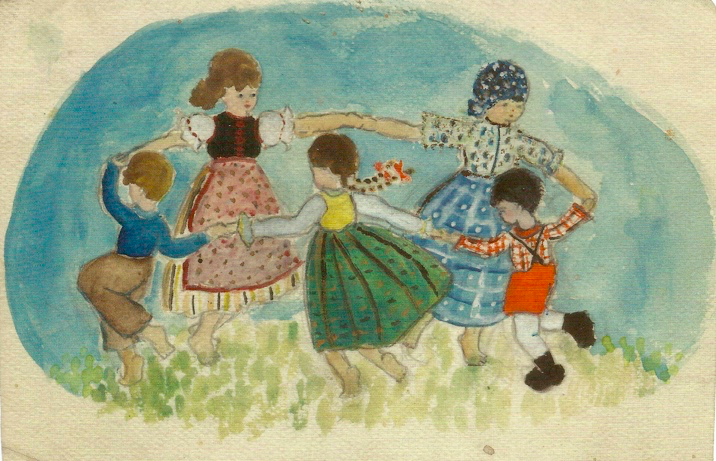

Examples of cheap print for children are attested before the 18th century. Book of secrets, containing recipes and medical remedies, were a successful genre already in the age of manuscripts; so successful that a Dutch publisher issued a book of secrets explicitly addressed to children as early as 1528. [picture 2]

A quite renowned collection of ballads preserved at the British Library and named after their collector, the Duke of Roxeburghe, contains at least two 17th century moral ballads that might have foreseen children as a privileged audience. [See banner image.]

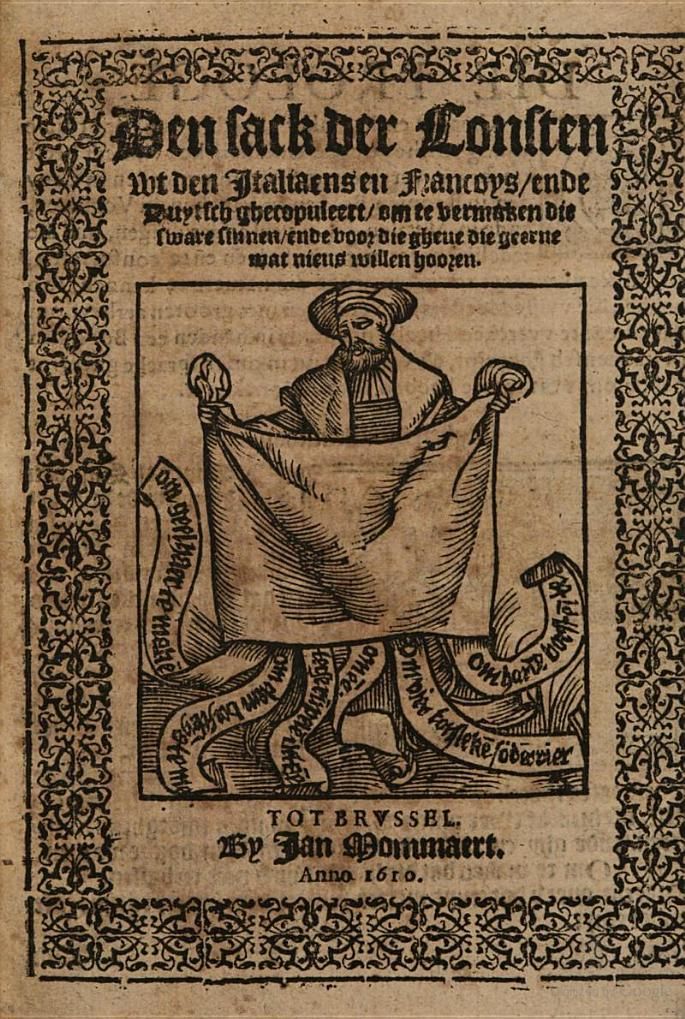

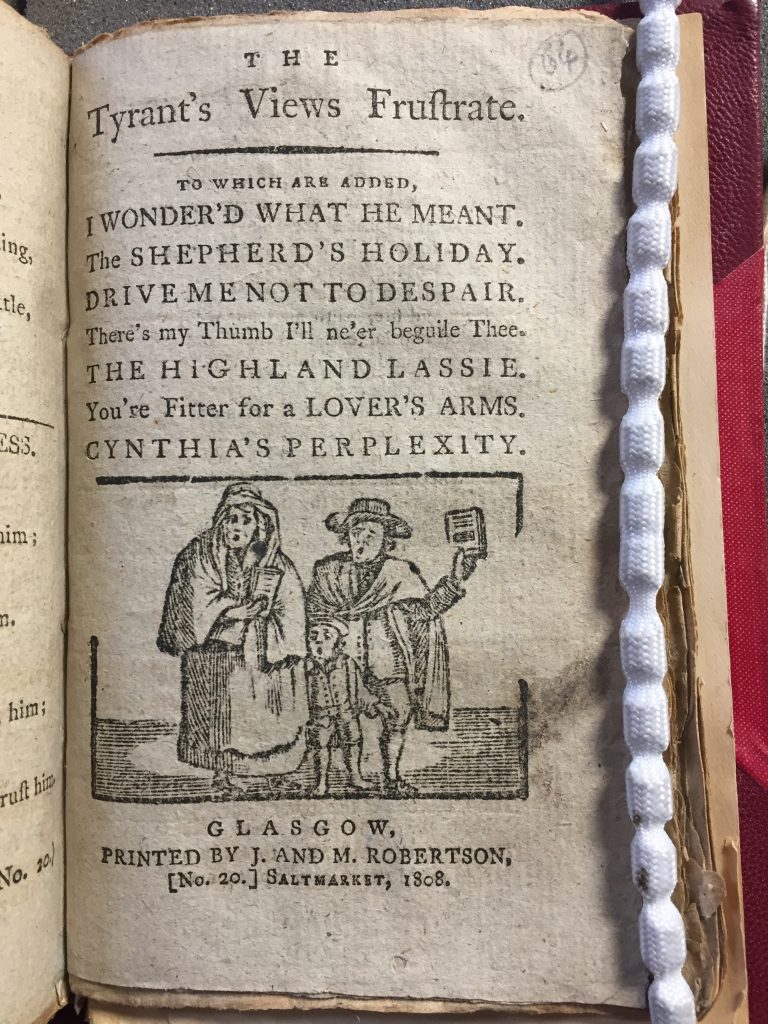

Moreover, children were likely to share cheap print with the rest of the society. Chapbooks printed in Glasgow by J and M. Robertson in the first two decades of the 19th century carry an interesting woodcut on their title page: it represents two adults and a child singing ballads together. This must have been an advertising strategy (title pages functioned as covers in chapbooks), and it is also evidence that cheap print of any kind would have reached juvenile audiences by the means of orality. [picture 4]

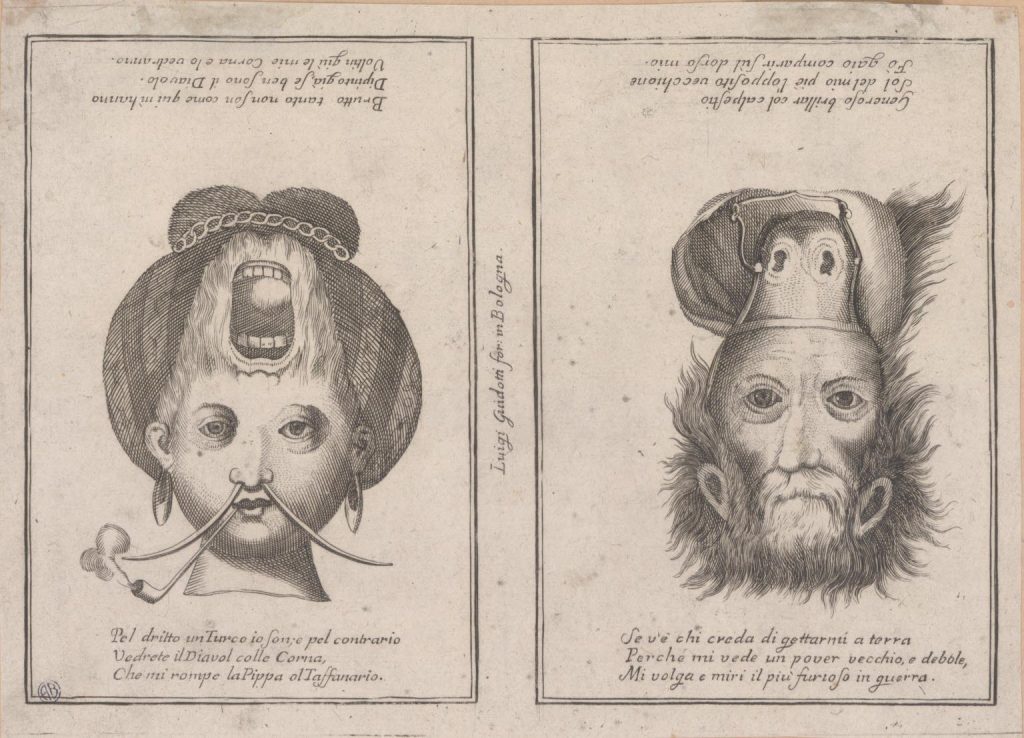

Printed broadsheets that narrated stories through pictures with a small amount of text as captions were probably appreciated by semi-literates, and for the same reason they must have encountered the attention of children. Sometimes they were not even conceived of as reading materials, but they contained a really limited amount of text, as in the Venetian fogli da ventola: single sheets mounted on a stick in order to be used as fans. They were not addressed to children, but there is evidence that young people were enjoying them as well, thus encountering written words even if they did not attend schools. [picture 5]

More didactic and educational printed materials must also be mentioned, such as ABCs, primers, catechisms, that represented, for instance, about the 18% of French chapbooks, the so-called Bibliothèque bleue. But they weren’t confined to schools, since it was not only young people that needed to practice on them. Moreover, it was not understood that children in schools had to read didactic books: in the 16th century the Venetian schoolmasters declared that children practiced reading on chivalric romances in cheap editions instead of using primers. And in the 18th century they still complained about that. Also in France, in the 17th century, bishops banned from schools fairy tales, romances and prophane books that were used to teach them to read.

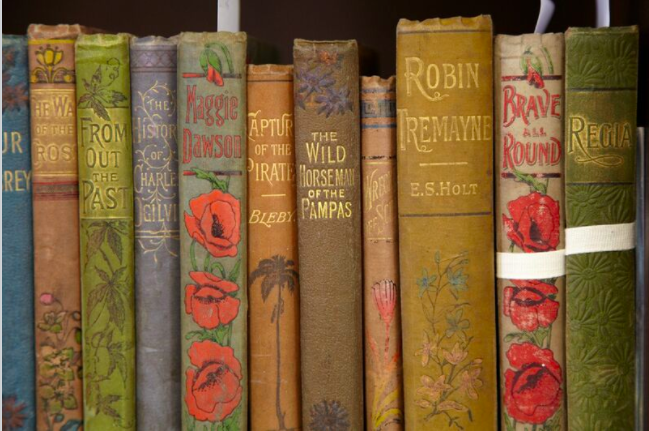

Social history research on 18th century France has shown that young peasants and thieves carried sorts of cheap print on their bodies when inspected by the police. Even in 18th and 19thcenturies, when books for children were increasingly issued, most families would not afford them. Cheap print for the general public was still an option; moreover, some clever publishers started to issue massively cheap print for children.

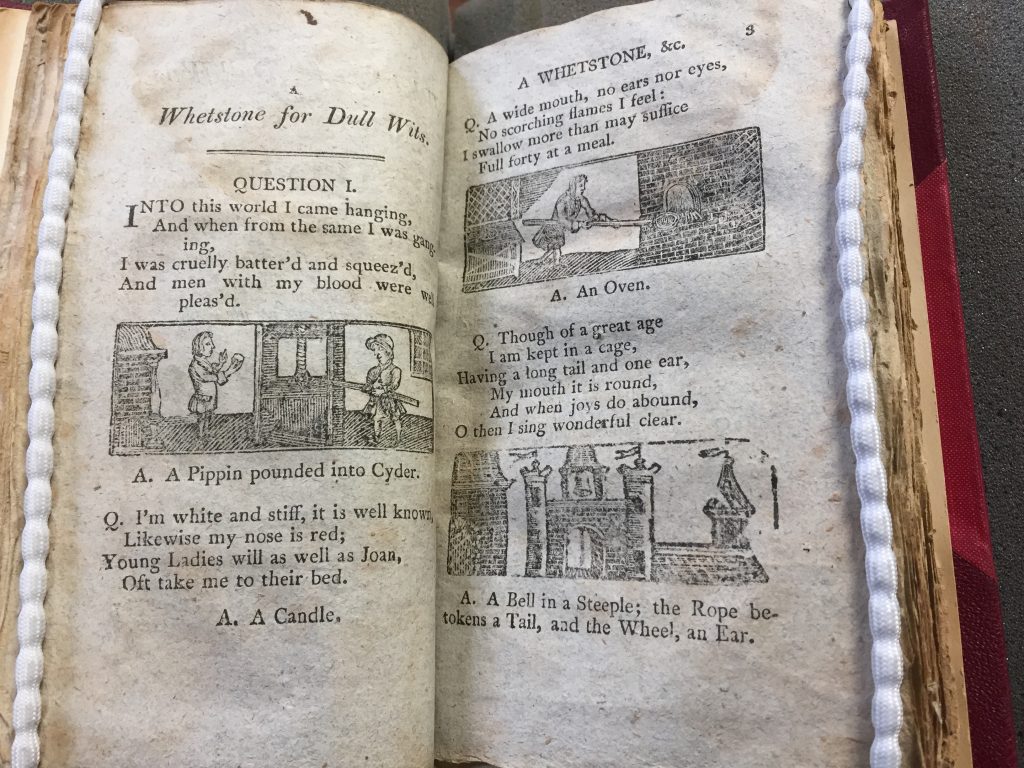

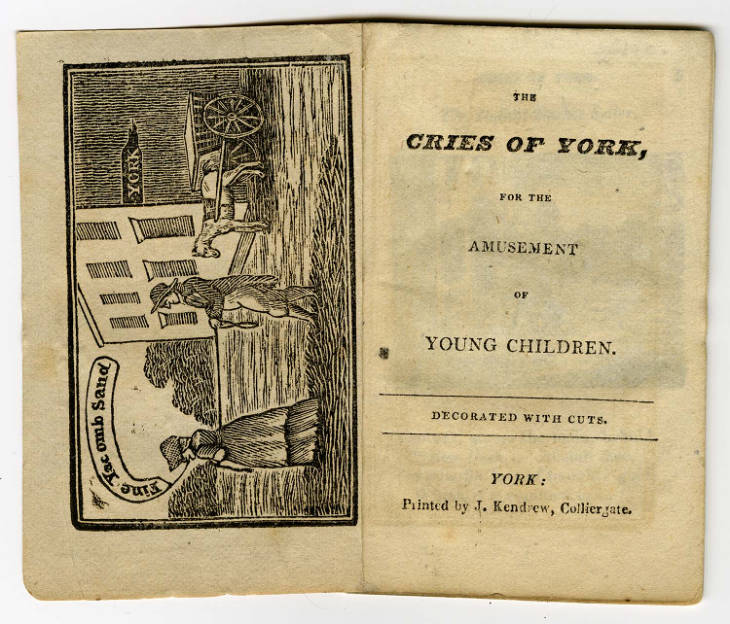

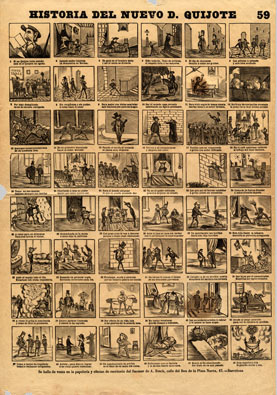

This British books of wits, printed probably in the early 19th century, has a larger number of woodcuts than the standard layout of a chapbook, and in fact it is specifically addressed to children. [picture 6] Chapbooks for children issued by Kendraw of York are among the most renowned examples [picture 7], but also in other countries cheap print for children became a proper publishing genre in the 19th century. Let us focus on Spain, where pliegos de aleluya, broadsheets containing images and captions, were used both as games (lottery) and as ancestors of comics. Traditionally addressed to the general audience, in the 19th century they were increasingly dedicated to children and proposed to them traditional narrations such as popular romances and fairy tales. [picture 8]

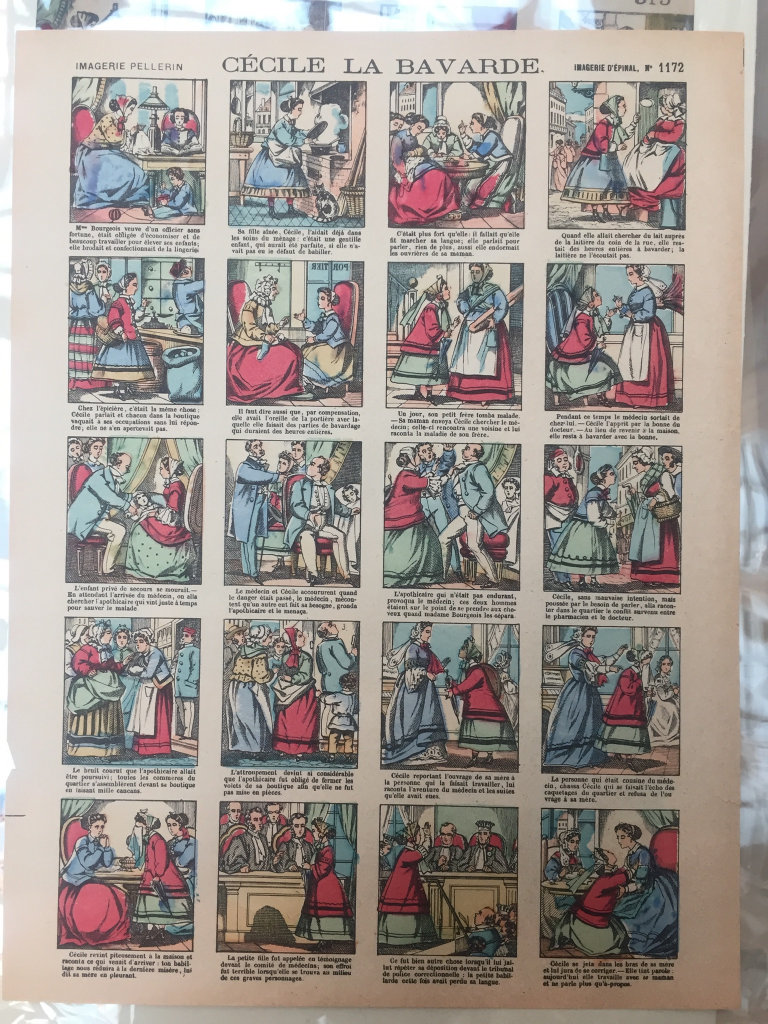

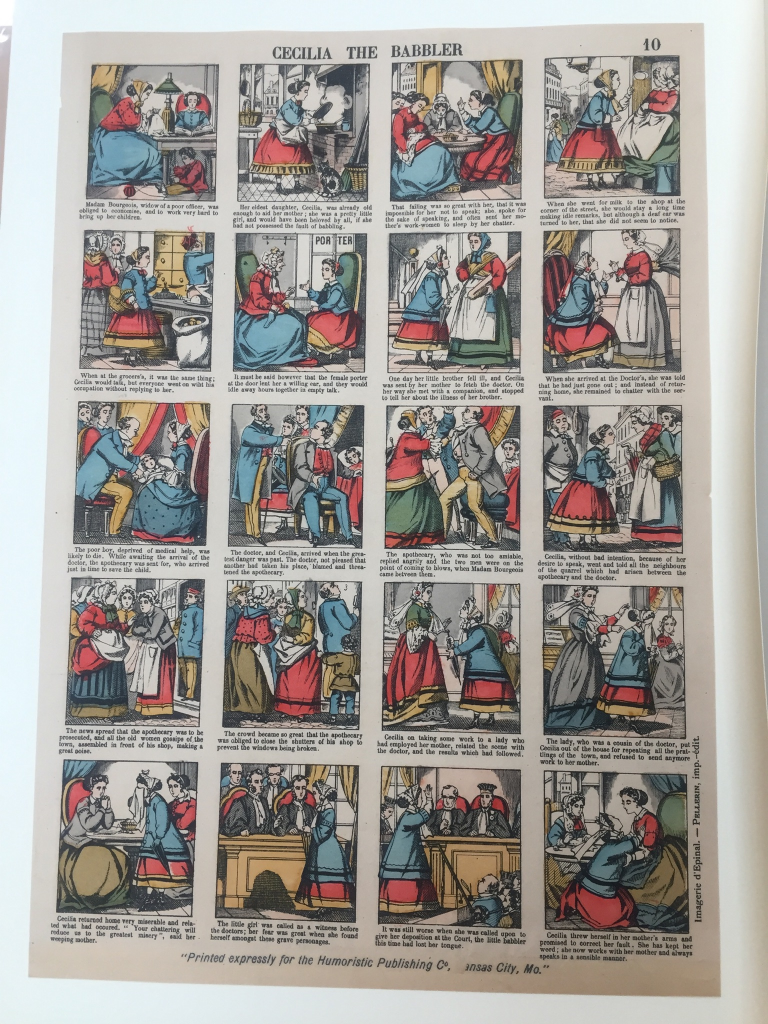

Similar products were printed all over Europe also before that the so called Imagerie Populaire was founded in Épinal, France, by Mr Pellerin. It was a printing shop specialising in lithography that took over the business of printed images selling them across Europe. Through some agreement Pellerin’s broadsheets were also translated into English and printed in the United States. [picture 9]

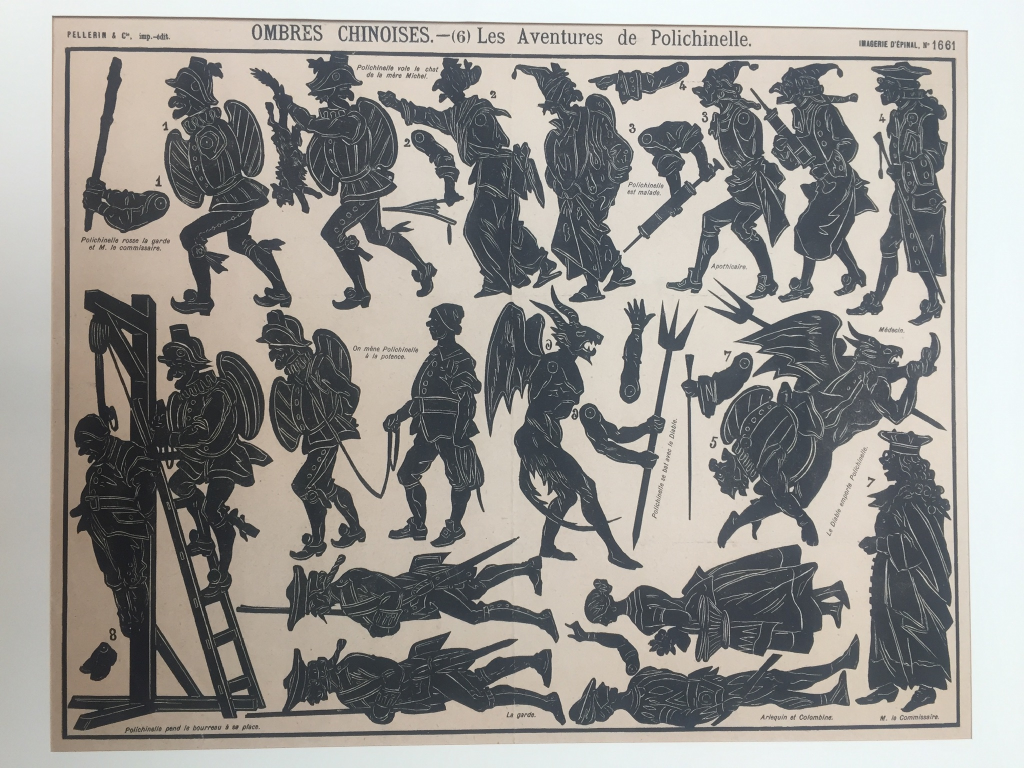

In addition, new printing techniques made illustrations and colours cheaper, so that broadsheets could even become cheap toys. Pellerin even printed a Chinese Shadow Theatre: sheets were intended to be pasted on cardboard and then cut in order to build the shadows of animals and people that would act on the stage of a cardboard theatre. [picture 10]

Research on all this is still at an early stage, but it is evident that cheap print represented a large part of the publishing market, especially in 18th and 19th century, and that it was often enjoyed by children. This means that we have only a partial understanding of what children were reading in the past. Cheap and ephemeral printed products are very likely to tell us more about that.

Elisa Marazzi is a Marie Skłodowska Curie Research Associate at the School of English, Literature, Language and Linguistics, Newcastle University.