Jamie Gomersall, MLitt Student

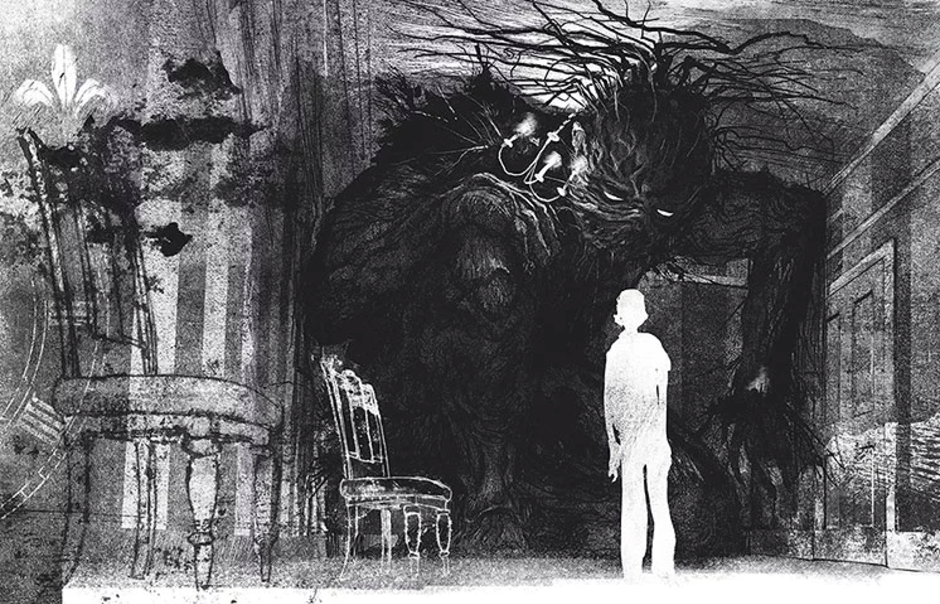

For a number of years, I have had a peripheral awareness of Edward Gorey’s work, but it was not until last Christmas that I received my very own copy of one of his books. Since then, I have fallen in love with his work. His gothic sensibilities, morbid sense of humour, and plots that frequently involve mysterious deaths in old country houses, or children being lured away by bizarre creatures, are ingredients that make Gorey’s picturebooks a treat to read.

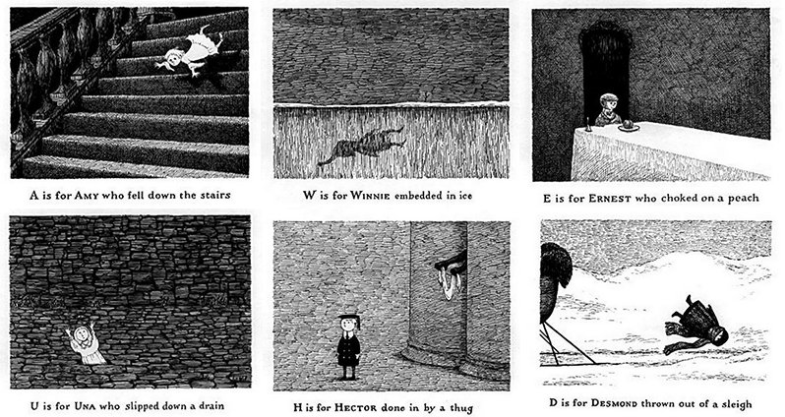

The first text of his I came across was a picturebook called The Gashlycrumb Tinies (1963), an alphabet book that lists twenty-six inventive ways in which a group of children come to a grizzly end. The book is amusing, in a macabre way, and illustrated with the beautiful pen-and-ink drawings that made Gorey famous. The Gashlycrumb Tinies displays many of the features one would expect from Gorey’s work, from the Victorian style of the fashion and the settings, to the rhyme scheme, and the prevalence of death as a major theme.

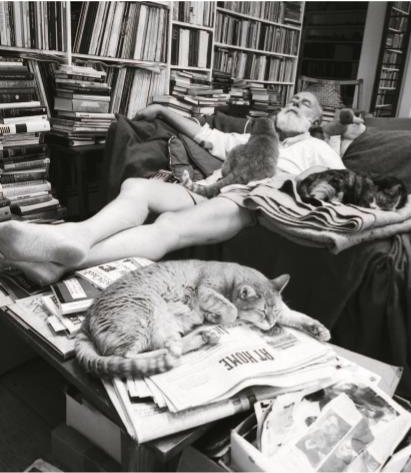

One of the things I find most intriguing about Gorey’s books is that they feel as though they belong to another time. The black-and-white illustrations would not be out of place in an austere Victorian-era children’s book. So stylistically old-fashioned are some of his books that I was surprised by how recently he was working. When I imagined the author behind these strange texts, I envisioned a pale and sinister Edgar Allen Poe type figure, scribbling down these ghoulish tales by candlelight. Even the name, ‘Gorey’, seems to suggest such a character. It turns out that the Edward Gorey in my head didn’t quite match the real-life Gorey, a bearded and bespectacled gentleman who lived in Cape Cod, Massachusetts, in a house he shared with his many cats.

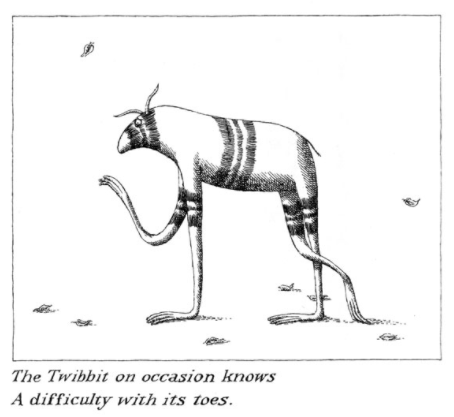

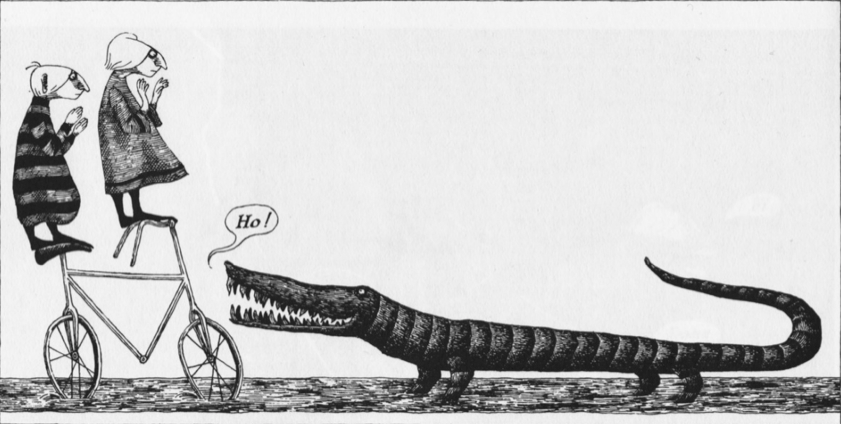

From 1953, up until his death in 2000, Gorey produced more than one hundred books, usually small hardback volumes with titles that are equal parts humorous and baffling, such as The Fatal Lozenge, The Glorious Nosebleed, and The Haunted Tea-Cosy. Though working in the twentieth-century, there is a definite nineteenth-century feel to his work, and in interviews he discusses having been influenced by writers of that period. He cites Lewis Carroll and Edward Lear as major influences, and that the tradition of British nonsense rhyme inspired much of his work. One of my favourite picture books by Gorey is an alphabet book called The Utter Zoo Alphabet (1967), which is certainly a descendent of the nonsense alphabets produced by Edward Lear. In this text, Gorey presents an A-Z of strange animals, from the Ampoo to the Zote, with short descriptions of each.

It is unsurprising that Gorey enjoyed a readership consisting of both children and adults. The books exhibit Gorey’s whimsical imagination, with fantastical creatures and suspenseful narratives that would pique the interest of child readers, while also having sinister undertones and an atmosphere of dread that adults such as myself are fascinated by. Not to mention, the illustrations are works of art in themselves. When asked why his children’s books were not as upbeat or colourful as those produced by his contemporaries, Gorey explained that he thought such work was tedious. He remarked, ‘Sunny, funny nonsense for children- oh, how boring, boring, boring’.[1] For Gorey, the edge of malevolence in his children’s books is what made them interesting. It might seem troubling that books like The Gashlycrumb Tinies, which depict the death of children with such relish, are read by children, but the deaths are often so absurd that they become more amusing than shocking. It is when the books have a foot in reality, however, that the result can be chilling. One such book is The Loathsome Couple, which I found particularly unsettling. The events in The Loathsome Couple are based on the Moors murders carried out by Ian Brady and Myra Hindley in the nineteen-sixties. Published in 1977, it chronicles a fictional couple, Harold Snedleigh and Mona Gritch, who lure children to a remote villa to murder them, until they are eventually discovered and arrested.

I found the way in which Gorey used the picturebook format, one that is so keenly associated with young children, to present a subject matter that is so horrific, nothing short of jarring. Gorey himself stated that it was ‘by far my most unpleasant book’[2], and it is easy to see why. Unlike his others, which would please both child and adult audiences, The Loathsome Couple is distinctly for adult readers, at least in my personal opinion. The others I have been cheerfully making my way through; though chilling, are chilling in a much more enjoyable way.

While Gorey was inspired by Carroll and Lear, his work has in turn inspired children’s authors working today. Lemony Snicket, for example, exhibits a similar gothic sensibility in his A Series of Unfortunate Events novels, which also hinge on placing children in dire situations. Philip Ardagh’s Eddie Dickens novels similarly makes use of Victorian settings, and the accompanying illustrations by David Roberts are very evocative of Gorey’s. It is no wonder that Gorey has left his mark on children’s literature, as his books are so peculiar that they must surely leave an impression on those who read him. His books are fascinating little marvels, brimming with deliciously dark humour, and I would heartily recommend them to all.

[1] Stephen Schiff, ‘Edward Gorey and the Tao of Nonsense’, The New Yorker, 9 November 1992, 84.

[2] Christopher Suefert, 2012. Edward Gorey Talks About the Utter Zoo (Mid-80’s Interview).