Professor Kim Reynolds

I recently completed a project based on the Catherine Storr archives at Seven Stories, the National Centre for Children’s Books, in Newcastle, UK. The task was to find a digital equivalent for visiting Seven Stories for those who can’t travel to Newcastle. The result was ‘The Catherine Storr Experience’: a 3-minute interactive virtual reality exhibition. You can read about it and view the exhibition here.

The Storr archives are a good example of the kinds of materials held at Seven Stories for they contain manuscripts in many formats, correspondence, contracts, illustrations, materials relating to adaptations, unpublished work, books, and memorabilia. The materials were deposited by Storr’s daughters, who loaned additional items and shared memories while the project was being developed. No exhibition can do more than indicate what an archive contains, and the nature of digital media means that the text for ‘The Catherine Storr Experience’ was quite limited. This is an opportunity to say a bit more about Storr, her work, and the shape of the project.

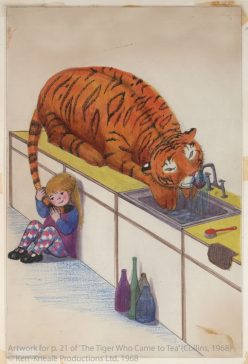

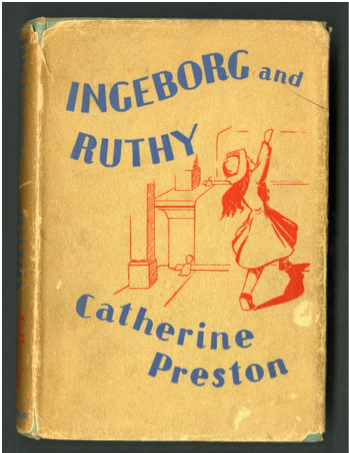

Before her success as a writer, Catherine Storr (1913-2001) qualified as a doctor, completing her training in 1944, the year her first daughter, Sophia, was born. By this time she had already published a children’s book, Ingeborg and Ruthy (1940) under the pen-name, Catherine Preston.

Writing had always been her chosen career, and though she worked as a psychotherapist at Middlesex Hospital from 1950-1960, being a mother inspired her to try her hand at writing again. Several of the stories she told, and sometimes turned into hand-made books for her three daughters, found their way into print. These include Stories for Jane (1952 which was originally called Stories for Sophia; Clever Polly and Other Stories (1952), written for her second daughter, Cecilia, known as Polly, and Lucy (1961), dedicated to her youngest daughter, Emma.

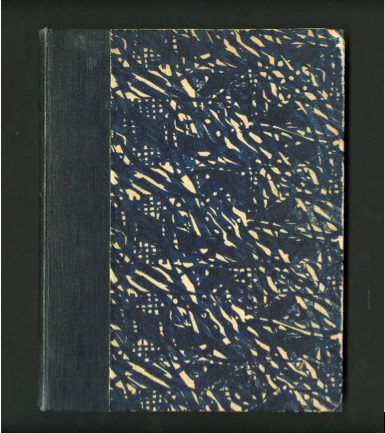

Storr’s mother was a talented book-binder and photographer and she bound some of Storr’s manuscripts, including Stories for Sophia, shown here.

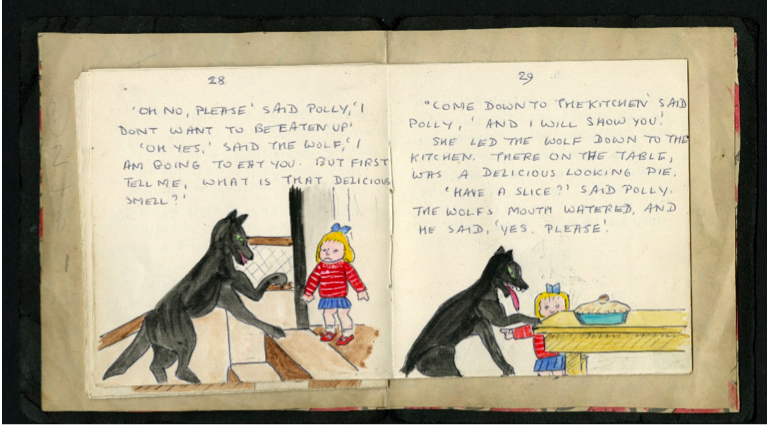

Later Storr assembled books for her children and grandchildren herself. The binding is less expert than her mother’s, but the stories are very amusing. Here is a page from her first attempt called ‘Naughty Sue’. Loosely based on Victorian cautionary tales, this contains the first of the Clever Polly stories.

Seven Stories also holds some of the manuscripts for the plays she wrote each Christmas for her children to perform in their puppet theatre. Although short, these were fully formed, with stage directions, songs, and special effects. Here’s a page from ‘Jack-and-the-Beanstalk’:

From the 1970s, Storr was a significant figure on the children’s publishing scene, speaking at academic conferences, contributing to scholarly publications, and reviewing books. Her most popular and enduring works are the Clever Polly stories (1952-57) and the novel Marianne Dreams (1958). Both have been reprinted many times, and Marianne Dreams was adapted for television, stage, and screen as well as being performed as an opera for which Storr wrote the libretto.

A prolific writer, Storr produced more than 30 novels for children as well as a number of picture books, retellings of classic tales, 6 novels for adults, 3 works of non-fiction, some music books for children and 2 libretti. Her last published work, The If Game (2001) was published posthumously.

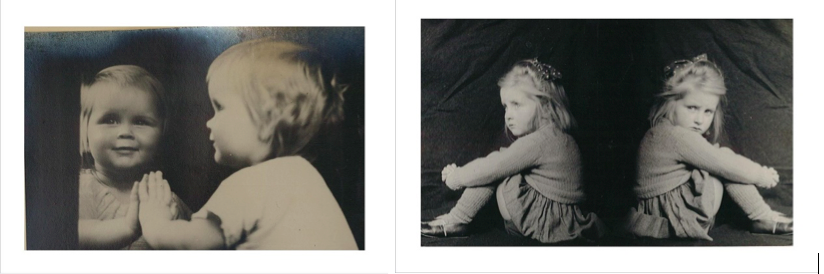

Although her work is very varied, certain themes recur. For ‘The Catherine Storr Experience’ I decided to focus on the motif of the double or doppleganger, which sometimes involved parallel worlds. The image of the double seems to have fascinated not just Storr, but also her mother. The family photo albums include images of Catherine Storr’s daughters reflected in mirrors or turned into twins using early examples of photographic illusions. Storr’s mother developed and printed these visual versions of doubles. Their textual equivalents fill the pages of Catherine Storr’s stories and novels.

In her books for younger children, doubles and other selves are often used to explore tensions in families: the desire to be more clever or special than siblings, for instance. For older readers, Storr uses doubles to explore growing interest in (and anxiety about) the opposite sex and as metaphors for the way selves can be lost through illness, drugs, toxic relationships, and despair.

The novels for older readers are often dark and sometimes frightening: Marianne Dreams was turned into the horror film Paperhouse (1989). Ultimately, however, all Storr’s young characters prove resilient, and healthy normality is regained. This combination of optimism and fear arising from emotions arising from aspects of the growing, changing self are grounded in the period in which Catherine Storr was writing. These were the formative years of children’s literature studies, when pedagogic, psychological and other professional aspects of childhood informed academic research on writing for children and young people. Much can be learned about the development of our field by spending time in the Storr archives – and many of the others held by Seven Stories.