Aishwarya Subramanian

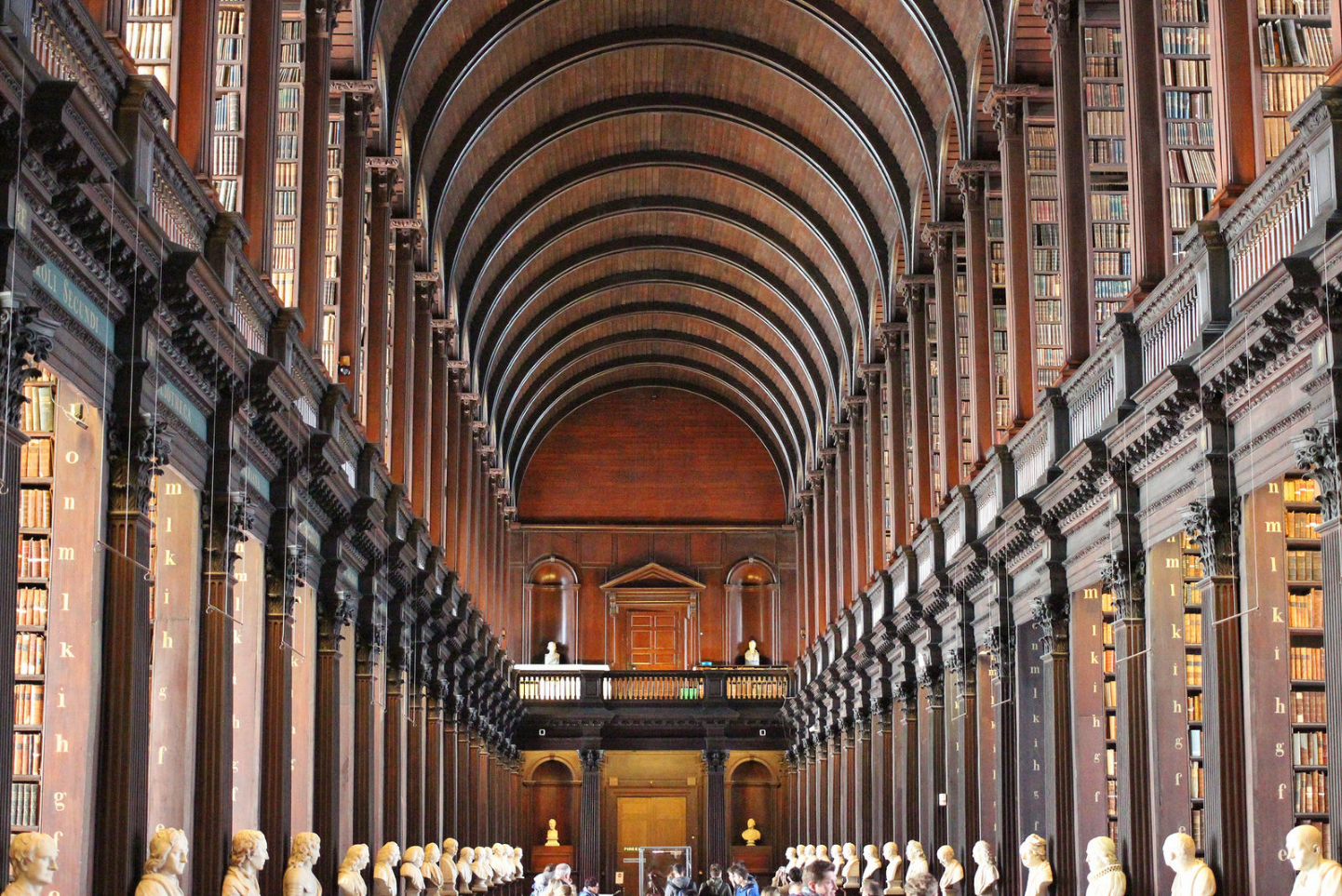

To get to the archives at Trinity College, Dublin, you have to walk through part of what is generally considered one of the most beautiful libraries in the world. This isn’t quite as wonderful as it sounds—it also means that you have to navigate your way through a crowd of tourists, often walking in the opposite direction, many of whom probably think you’re jumping the queue. (You may be, as I was, told off by an indignant small child.) You are repaid, however, with the chance to flash your reader’s card and walk smugly through the cordoned-off door at the end of the room.

This is not a complaint about tourists—at least part of my smugness was borne of being allowed a shortcut through spaces I’ve had to queue up to see in the past. But there’s lots to be said about the library as an institution, as a site for tourism; about the fact that lists of the most beautiful libraries in the world are a phenomenon in the first place (for example, ‘The Most Spectacular Libraries Around the World‘, ‘Best Libraries Around the World‘, ‘16 Breathtakingly Beautiful Libraries from Around the World‘, ‘15 of the Most Beautiful Libraries in the World‘).

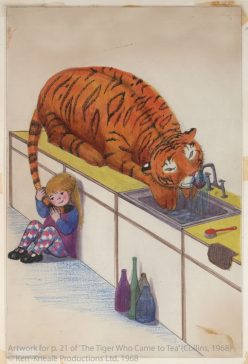

There’s a library in the book I was there to work on. Late in Michael de Larrabeiti’s The Borribles (1976), two of our heroes come across the library of their mortal enemies, the Rumbles:

It was a long, high chamber, with massively tall bookcases soaring up to an embossed ceiling that had been painted with the coats of arms of the richest and most ancient Rumble families […] Here was assembled all the knowledge, wisdom and power that the Rumbles had amassed over many centuries, and now it was being dismantled by a very busy Borrible.

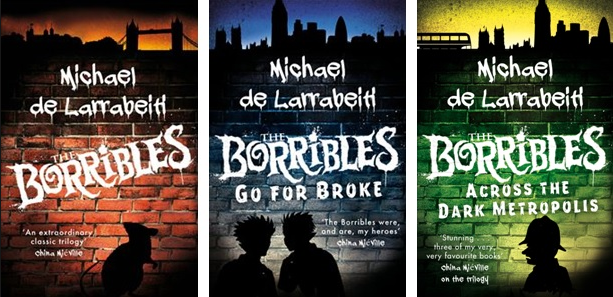

The Borribles, along with the books that follow it, The Borribles Go For Broke (1981) and Across the Dark Metropolis (1986), has an uneasy relationship with the literature that came before it. Most critics, if they mention the series at all, will describe it as a parody of Elisabeth Beresford’s Wombles series—it’s hardly subtle either about its connection to those books or its opinion of them. In de Larrabeiti’s series the “Rumbles of Rumbledom”, with names like Oroccoco, Vulgarian, Napoleon Boot (corresponding to Beresford’s Orinoco, Great Uncle Bulgaria and Wellington), are acquisitive rodents who live lives that range from comfortably middle-class to outright decadent, and who are considered repulsive by the Borribles, to whom the concept of money is abhorrent. Borribles own nothing—even their names are fought for. (In The Borribles, our heroes adopt the names of the Rumbles they kill.) But the Wombles aren’t the only literary reference here—diminutive humans who often live under houses and sustain themselves by stealing only as much as they need, the Borribles are also reminiscent of Mary Norton’s Borrowers and this fact is echoed in their name. And perhaps most importantly, as children who run away and thus avoid ever growing up, they’re a version of Peter Pan‘s Lost Boys. These are not the only figures in the children’s literary canon to whom they can be compared, though. In Across the Dark Metropolis, a character attempts to restrict knowledge of the Borribles to “the realm of hobbits, boy wizards* and bunnies.”

The point, of course, is that the Borribles are not hobbits, not Borrowers, definitely not Wombles; they’re constructed in opposition to this literary canon and all that it represents. Their natural allies, we learn as the series progresses, are outsiders—immigrants, racial minorities, circus folk, the homeless; at one point we meet an all-woman punk commune of Borribles who to me are always coded queer. In the later books the Borribles are pursued by “the SBG”, a police group blatantly modelled after the Special Patrol Group (SPG) of the London Metropolitan police. In 1985, de Larrabeiti’s publishers would refuse to publish Across the Dark Metropolis because in the wake of the Brixton riots the book’s political sympathies were a little too clear.

And so the Borribles burn the library down:

[Napoleon] went over to a pile of dusty tomes, put a match to them, and stood back as they burst into flames on the instant.

“What I mean,” persisted Bingo, “is that it’s a shame; they’re good things, books.”

“Good things! You sound like a bloody Rumble […] What would happen if we left these books up here untouched? I’ll tell you what, there’d be another Rumble High Command on the go in five minutes. This is what it’s all about, Sonny—books is power! The whole world knows that.” And Napoleon threw another volume into the blaze.

Books are power—libraries, like literary canons, are institutions that oppress. It’s testament to the book’s power that here the reader feels something like triumph at the burning down of this library. But we also feel, with Bingo, that it’s a shame.

And for all Napoleon’s hardline stance, the books do recognise the importance of literature (and as intertextual as they are, they could hardly exist without it) and literary record. The adventurers in The Borribles are accompanied by a historian, a more experienced Borrible whose job it is to record their story for posterity. As the series progresses the importance of this alternative literary record, of actively telling this story, becomes more and more clear. The Borribles represent a history of resistance that their enemies want to un-write—want, in fact, to keep in “the realm of hobbits, boy wizards and bunnies.”

In our own political dark times, as it grows ever harder to imagine alternatives to the present, it has been important to me to remember that these books, and others, existed; that however imperfect, they offered models of strength and solidarity. For this reason above all others I’m glad that the de Larrabeiti archive exists, even if it is in one of the Most Beautiful Libraries in the World.

*Not that boy wizard; Across the Dark Metropolis was published in the 1980s. (It’s not hard to imagine what the Borribles would think of Hogwarts, though … )