Dr Lucy Pearson

The anniversary of 1968 approaches, and with it memories of radical change: workers and students united on the streets of Paris; draft resisters and anti-Vietnam protesters; flower power and violent revolution. The 60s revolution is usually regarded as a youth phenomenon, yet little attention is paid to the literal ‘children of the revolution’. This is the gap that Sophie Heywood proposed to address with her research network on The Children’s 68. On October 12th, CLU colleagues Kim Reynolds and Lucy Pearson headed off to Tours, France, for an interdisciplinary conference organised by Sophie Heywood and Cécile Boulaire exploring the many dimensions of childhood and ‘the spirit of ‘68’.

The conference brought together scholars from many different countries and many disciplines. For some of us, 1968 was clearly a landmark moment, while others questioned whether there was a ’68 moment at all in our countries of interest. Topics included children’s books, radical magazines, television, art culture, feminism and workers’ rights. What emerged from this comparative approach was that there were many correspondences across the experiences of different nations, but also that even within a single cultural context the ‘meaning’ of ’68 encompasses a variety of different and often conflicting ideas.

There were many examples of culture which tried to give children a voice or encourage them to resist the power of adults. Olle Widhe’s paper on the children’s rights movement in Sweden, for example, showed us books which encouraged adults to resist the ‘indoctrination’ of their children, and encouraged children themselves to rise up against the power of adults. Bettina Kümmerling-Meibauer, on the other hand, showed that West German texts sought to ally children with other marginalised groups: a collaborative revolution in which children helped to overcome the systems of power.

Kim Reynolds vividly evoked the feelings of power and possibility experienced by children and young adults in 1968 USA, and showed that while children’s culture failed to produce texts directly addressing the Vietnam War, these young people co-opted the adult culture of popular music to articulate their feelings and beliefs. Other papers, though, raised the possibility that the child was co-opted by adults as a symbol for their own ideologies and desires. Andrea Francke showed a range of exciting picturebooks which questioned the existing social order, but ruefully acknowledged that while these were exciting and important for the women in the feminist collectives who produced them, many children found them uninteresting. In David Buckingham’s paper on the controversial schoolkids’ issue of Oz magazine, he suggested that the magazine included both the authentic concerns of schoolchildren and a discourse around childhood which served the interests of the adult men who edited the magazine.

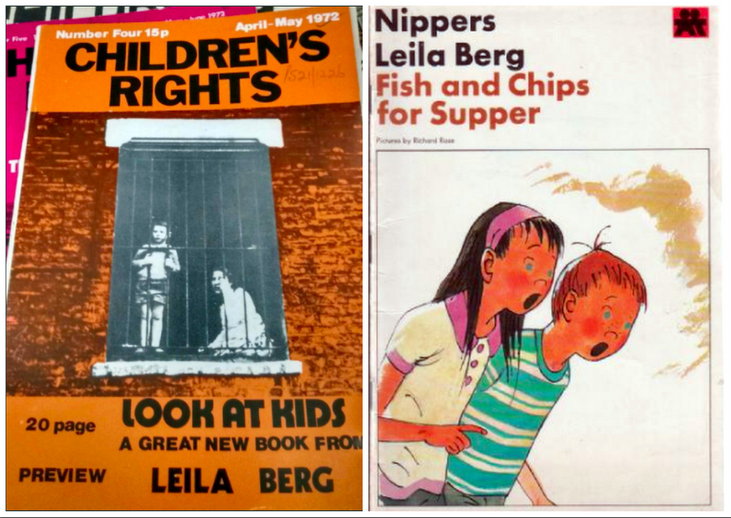

One striking theme was the degree to which this ‘counter-cultural’ moment was institutionally supported and disseminated. Helle Strandgaard Jensen showed that the state broadcasting of Denmark incorporated radical voices into its children’s television. My own paper, on Leila Berg’s Nippers series, considered the intersection between progressive education and mainstream educational publishing and policy. Cécile Boulaire showed that even traditional Catholic publishers in France produced radical material in the form of children’s magazine Okapi.

Another theme which preoccupied me throughout the conference was the question of intersectionality. One of the most striking aspects of the May ’68 revolution in Paris was the way it brought together different constituencies: students and workers manned the barricades together.

Yet I felt that very few of the examples considered fully expressed such unity between children’s rights and the interests of other groups. Children are not only children, of course: they are also defined by their gender, class, ability, race etc. Many texts sought to explore the power dynamics of such categories, and many promoted the rights and agency of the child, but neither the cultural productions of the sixties nor our scholarship achieved a fully intersectional understanding of childhood. I wondered if this gap was a partial explanation for our sense that many of these radical ideas had not had as great a legacy as some of us wished.

The conference closed with the accounts of practitioners: children’s librarians, curators, and educators. Alex Thorp, Education Curator at London’s Serpentine Gallery, showed some fascinating examples of projects which demonstrated the radical potential of play and the degree to which the young people of today continue to experience their relationship with the adult world as one of oppression. All the discussion in this closing session drew attention to a crucial gap in the conference discussion: almost none of our papers included the accounts of actual children. For scholars of childhood, the question of how to include the child’s voice is a perennial problem, but our subject really brought this to the fore. The network hopes to partially address this in an exhibition on ‘Le ’68 des enfants’ taking place May-June 2018, to be held at the French children’s archive Heure Joyeuse, preserved at the Mediathèque Françoise Sagan. Working with graphic designer Loic Boyer, the archive will develop an interactive exhibition which invites children to participate; accompanying workshops with illustrators will also help to bring children’s voices to the fore.

It was a stimulating few days which generated many productive conversations and (I hope) some lasting collaborations. For me, it was a great reminder of how interlinked different aspects of children’s culture are: I can’t wait to do more work with colleagues from other disciplines. Perhaps together we can revive something of the spirit of ’68!

Perhaps some of you were ‘children of ‘68’ – or the children of those children! What was the spirit in your country? And how has it shaped children’s culture today?