By Enya-Marie Clay, MLitt Student

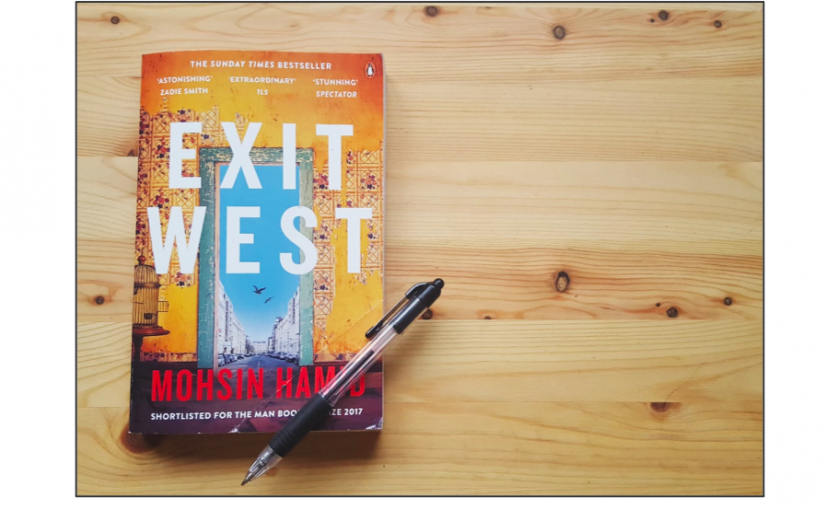

Shortlisted for the Man Booker Prize in 2017, Mohsin Hamid’s Exit West follows the relationship of Nadia and Saeed who endure a difficult journey in search of safety and belonging after their escape from a war-torn country through a magical door. The doors that emerge in the novel – instantly transporting passers-through to a random location in the world – serve as an optimistic vision of a borderless future raising questions about identity, transience, and belonging.

As part of Newcastle University’s participation in the Booker Prize Foundation’s One Book Project, free copies of Exit West were offered to students across the University campus. This culminated in the One Book Event on Monday 29th October during which author Mohsin Hamid was in conversation with Newcastle University’s Dr Neelam Srivastava about his latest novel.[1] This free, public event provided an accessible way for students and members of the public to engage with the book, explore its themes, and connect with its author. The event was a huge success with engaging conversation, a full audience, and plenty of opportunity to ask questions followed by a book signing by Hamid.

The evening opened with Hamid reading a passage from his book – one of the many micro-stories featuring in the novel. In Hamid’s selection, we see an extract from the micro-story of an old woman who, surrounded by youth, modernity, and change, muses that we are all “migrants through time.”[2] Transience and temporariness are central themes in Exit West and this is comparable to the arc of maturation often found in adolescent fiction. It reminds us that transience is a universal experience transcending race, culture, and time, yet it is one we tend not to acknowledge out of a desire for the illusion of permanence and belonging. Hamid compares this to anxieties about mortality, of ourselves and of our loved ones. These themes of temporariness and mortality are common throughout teenage fiction novels and one of my key research interests is exploring how they are navigated in teenage Holocaust fiction.

An intriguing aspect of Holocaust fiction’s popularity among teenage readers is their curiosity regarding issues of trauma, death, and identity – elements that feature prominently in Holocaust fiction by its very nature. Hamid’s poignant discourse in both Exit West and his other writings on the falsehood of permanence also relate to Holocaust literature and education. A key message of Holocaust commemoration is, ‘never again’, yet how often do we see this message weakened by stories of conflict, prejudice, and genocide in headline news? And how do we then communicate to young readers that Holocaust fiction is about the past when the issues it explores are still very much prevalent in our society? My MLitt research underlines the view that we shouldn’t – these themes deserve our attention and the creation of accessible Holocaust fiction for young readers is a viable way to bridge gaps in education and to explore many of the issues Hamid’s Exit West discusses.

In an interview with the Guardian in August, Hamid said that children’s stories are the best examples of how a story can speak to humanity as a whole.[3] I asked him, considering that statement, whether he would write a children’s story himself in the future. He said he would like to but hadn’t gotten around to it yet, then explained that his first novel was a cynical response to ideas of purity and that, while his following two novels featured destabilised narratives, Exit West’s narrative style was inspired by children’s books.

…[Saeed] he touched a feeling that we are all children who lose our parents, all of us, every man and woman and boy and girl, and we too will all be lost by those who come after us and love us, and this loss unites humanity, unites every human being, the temporary nature of our own being-ness, and all our shared sorrow, the heartache we each carry and yet too often refuse to acknowledge in each other, and out of this Saeed felt it might be possible, in the face of death, to believe in humanity’s potential for building a better world (p. 202).

On reading Exit West, with its raw exploration of difficult questions surrounding identity, transience and belonging against the backdrop of negotiating culture clashes and escaping conflict, you may be surprised to find out its style was inspired by children’s fiction. Yet it is the double-partisan way in which children’s literature involves and challenges the reader, by its ability to be both straightforward and complex in adapting to the needs and maturity of its audience, that inspired Hamid’s writing style in Exit West. Hamid said this in response to the question I put to him at the One Book Event, stating that, in the face of the popularity of fake news, there is value in putting the reader on the side of the character to explore an issue. He compared it to the effect of Charlotte’s Web in the reader’s involvement in urging Wilbur not to die – he wanted Exit West to give readers the same involvement with its characters.

Exit West gives raw emotionality and human experience to the stories we are all familiar with seeing on the news. Its manner of taking the reader out of their comfort zone without having the effect of preaching privilege encourages reflection as it explores issues that affect us all without condemnation or outright judgement of any particular group. As issues of identity and belonging become more contentious and politicised, Hamid’s voice is an important one. One day, his voice will be a valuable contribution to succeeding generations should he write a book for younger audiences. Until then, it’s up to us adults to learn, co-operate, and act to improve the world for those that will follow.

[1] “Award-Winning Author To Speak At Newcastle University“. 2018. Newcastle University Press Office.

[2] Hamid, Mohsin. 2017. Exit West. Penguin Books. p. 209.

[3] Preston, Alex. August 2018. “Mohsin Hamid: ‘It’s important not to live one’s life gazing towards the future’ [Interview]”. The Guardian, 2018.