A pioneer of the British girls’ school story is commemorated at the 2017 Edinburgh Festival Fringe

Jennifer Shelley

To the Edinburgh Festival Fringe to see For the School Colours, a show based on the life and works of Angela Brazil – well, who could resist?

It’s being put on in a typical, small Fringe venue just off the Royal Mile, by Not Cricket Productions, a company that is developing a reputation for producing shows based on classic texts and tales.

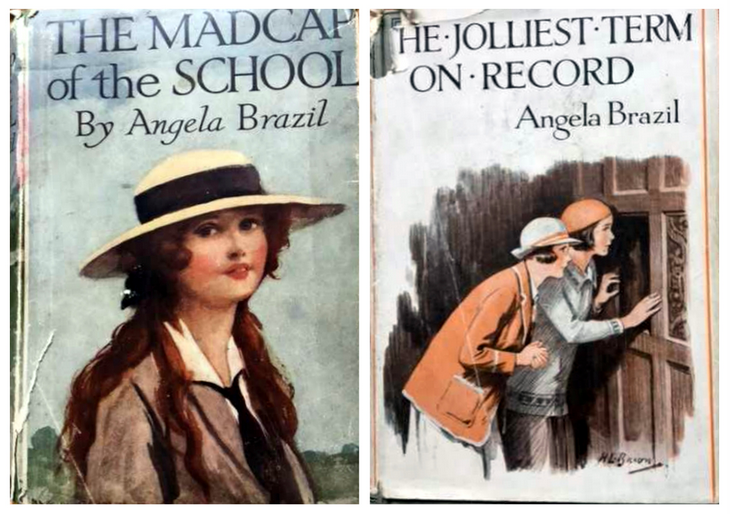

Not Cricket’s other offering at this year’s Fringe is the better-known Alice in Wonderland, but it was the For the School Colours that attracted me. Regarded as one of the ‘Big Four’* in terms of early 20th century writers of school stories for girls, Brazil is probably the one I know least about – and yet she repays some attention. To today’s eyes, her work appears to embody the worst of the clichés of girls’ school stories, as lampooned by the likes of the musical Daisy Pulls it Off; it’s hard to keep a straight face when reciting some of the titles, such as The Jolliest Term on Record (1915), The Madcap of the School (1917), or Joan’s Best Chum (1926). But Brazil was to an extent a pioneer. Of course she didn’t invent the school story, but she is recognised for doing much to develop and popularise it, and for writing books for the entertainment of modern girls. Indeed, the blurb for the show suggests that she paved the way for writers such as Enid Blyton and even J. K. Rowling, but that’s a discussion for another day.

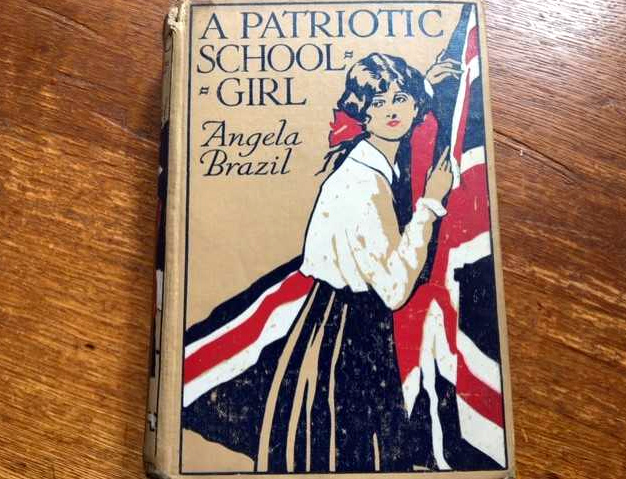

The play has clearly been well-researched, and acknowledges that little is actually known about the life writer, who lived from 1868 to 1947. Brazil did leave an autobiography, but it painted a very rosy picture, for example, making her family out to be grander than it was, and glossing over anything not quite ‘respectable’. A later biography by Gillian Freeman was published in 1974, and covered such delights as Brazil’s unexpected correspondence with Marie Stopes, including a letter discussing whether the school stories would translate to stage or screen. Although this production mines these resources, writer Kate Stephenson has also turned to Brazil’s fiction for clues about the author’s life. For example, the company acts scenes from A Patriotic Schoolgirl (1918), where a respectable schoolteacher has to explain to her pupils why her nephew is being brought up in a household that is distinctly below her station. The play draws parallels between this and Brazil’s own brother, who apparently cut himself off from his sister when she would not accept his marriage to someone considered not good enough.

The play gives the overwhelming impression that when it comes to Angela Brazil, what you see is probably not what you get, even with something as basic as pronunciation of her surname. Although she herself voiced it to rhyme with dazzle, the play suggests that her parents and brother chose to call themselves Brazil, as in the country. I found that particularly amusing, partly because in certain fandoms, how you pronounce Brazil is almost a secret sign for identifying the ‘cognoscenti’ (another is knowing that Noel Streatfeild is spelt e-before-i). So it’s nice to know that this form of elitism was based on something just as dubious.

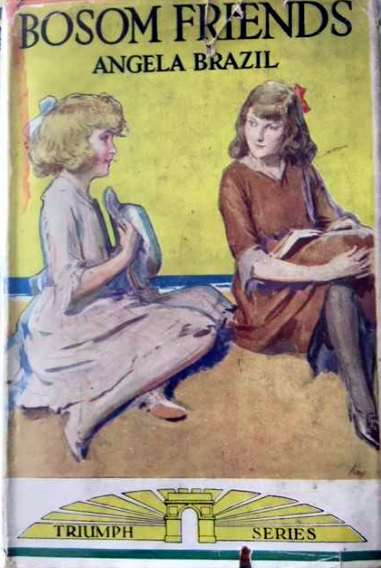

I came to Angela Brazil as an adult, and almost didn’t get to know her at all. The opening few lines of the first novel I downloaded (there are lots available for free from Project Gutenberg) were off-putting, filled with ridiculous slang and ‘harum scarum’ characters getting up to gratuitous mischief. A friend persuaded me to give it another go, and suggested starting with Bosom Friends (1910), one of Brazil’s earlier works, and a ‘holiday’ rather than a ‘school’ story. It was a completely different experience: set in a seaside town, it concerns a friendship between two girls who have very similar names, but are opposites in almost every other respect. One is kind and caring and intelligent – and poor – while the other is a selfish and dishonest spoilt darling with ‘fluffy’ blonde curls and a taste for finery (usually a sign of a bad egg in 20th century girls’ fiction). It’s a charming book and the heroine, Isobel, is a delight. Although her near-namesake, Belle, is a trifle overdrawn, and the plot is a little too coincidence-heavy, Bosom Friends is a fabulous gateway into Brazil’s other work.

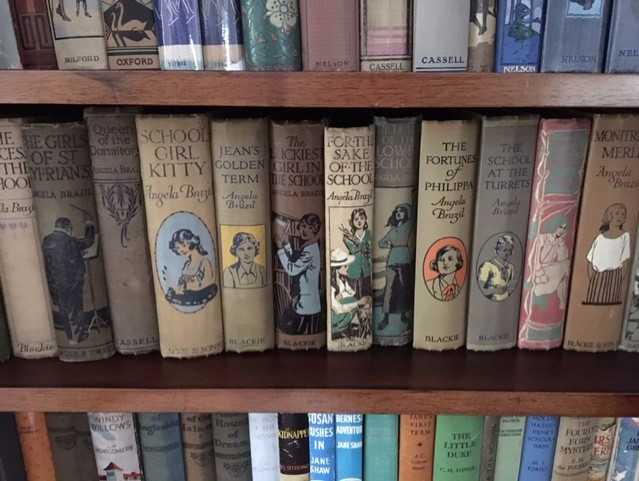

For me, it led me to ‘binge’ on the other Brazils available on Project Gutenberg, and then to start collecting early editions of the books where I could find them. Most of them were published by Blackie, and are very attractive, with gorgeous covers, as well as being fun to read.

I was curious to know what had inspired Not Cricket Productions to pick on Brazil, and waited behind to speak to Stephenson, who is the director as well as the writer. She told me that she had started reading Angela Brazil when researching for her PhD, on the history of school uniform. Her thesis is that school stories influenced clothing codes that were adopted in schools, and she said that the works of Angela Brazil just kept coming up in her research, and the fascination started there. She’s trying to turn it into a book – but jokingly complains that theatre keeps getting in the way.

All in all, I felt it really worked as a show, and would recommend it if anyone wants to spend a pleasant and interesting hour at the Fringe. It has also inspired me to find out more about Brazil herself. Watching the play, I wasn’t sure what was based on fact, and what was speculation, but that didn’t mar the enjoyment; I’ve ordered a copy of the Freeman biography, and I’m looking forward to finding out more.

* The others generally included in the ‘Big Four’ are my particular favourite Elinor Brent-Dyer, who wrote the Chalet School series; Dorita Fairlie-Bruce, author of the Dimsie and Springdale books, and Elsie J Oxenham of Abbey fame. Your views may vary – if so, feel free to respond in the comments section below.