Dr Alistair Clark

Alistair Clark is Senior Lecturer in Politics in the School of Geography, Politics and Sociology. His research interests revolve around electoral integrity and administration, political parties and party organisation. His current research explores various aspects of electoral integrity and election costs. In this blog post, Alistair explores a key issue of interest to both policymakers and scholars of electoral integrity: whether or not higher spending on election administration actually improves the quality of elections.

Running elections in advanced democracies is an expensive business. Yet, in many countries, the cost of politics is under pressure. This pressure extends to the ‘backroom’ costs of administering elections. To do so in a fair, equitable and transparent manner nevertheless necessitates a range of spending, without which the potential integrity of the electoral process is put at risk. Little however is known about the effects of such spending on election quality. My recently published chapter ‘Investing in Electoral Management’ (in P. Norris et al (eds.) 2014 Advancing Electoral Integrity, Oxford University Press) addresses this issue in an attempt not only to begin a debate around election costs, but to begin to provide evidence to policymakers about the effectiveness of spending on election administration.

Far from being a centralised process, running elections is hugely complex and something that must, by definition, happen close to the voter. Polling stations need to be identified and set up, poll workers employed and trained, and enough ballot papers printed. Votes then need to be kept secret and secure, counted, collated and the results published. However, electoral law is often fragmentary, with different laws made in different jurisdictions. Small problems can easily become larger ones; witness, for example, the election night queues in some English cities in the 2010 general election.

One explanation often given for difficulties in electoral administration is the lack of resources available to pay for a range of electoral facilities. These can range from the highly complex – electronic voting and counting machines for instance – to the seemingly more mundane – making sure enough part-time workers are recruited and trained to man the polls and count the votes. For example, although the Help America Vote Act 2002 mandated and provided funding to update US electoral administration in the aftermath of the Bush-Gore fiasco, it is commonly noted that the subsequent Election Assistance Commission it set up had difficulties in executing its functions because of a lack of finance. Similarly, in Britain, under-resourcing is often cited as a factor in explaining why difficulties occur.

The corollary of this argument is to suggest that if electoral administrators were better funded, there would be fewer problems and better run elections. This is an important argument, going to the heart of what must be the central aim of electoral administration: that everyone who is eligible can cast a vote, and that their vote will be counted in the same way as everyone else’s. The argument is that proper resourcing helps deliver this. Under-resourcing puts it at risk. Running elections is seldom the first priority for public administrations. With current austerity policies pressuring public service budgets, running elections is likely to assume an even lower level of priority.

What is the evidence that higher levels of spending delivers better quality elections? This has remained largely unexamined because consistent data on both the performance of electoral administration and on the funding of electoral services is extremely difficult to find. This is for a variety of reasons. Public bodies are seldom mandated to monitor performance in this field, even if outside election observers often do, while accounting consistently for spending on elections across a range of local public bodies which implement the elections is extremely difficult.

Fortunately, performance and spending data collected by the UK Electoral Commission provides some insight into whether spending on election services delivers better quality elections. In ‘Investing in Electoral Management’ an index of electoral integrity created from returning officers performance standards in the 2009 European elections in Britain was brought together with data on spending on both electoral registration and on the practical aspects of running elections in 2008-09, immediately prior to the European elections, from almost all returning officers across Britain. This allowed a number of ideas to be tested. These are that:

- Electoral management performance improves with more spending on electoral administration.

- Electoral management performance improves with more spending on electoral registration activities.

- Electoral management performance improves with more spending on the practical aspects of election administration.

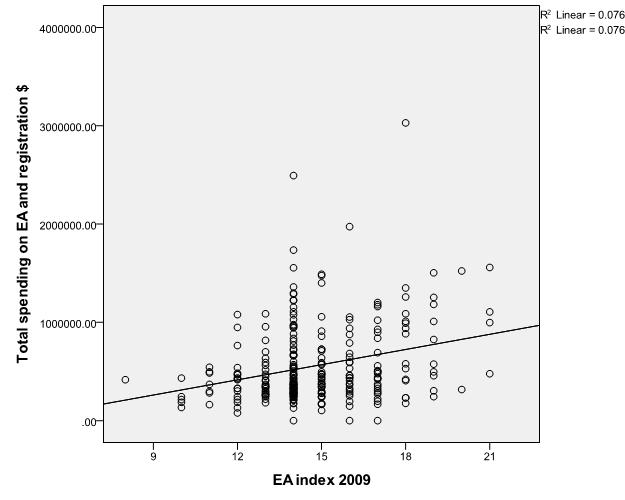

Figure 1: Relationship between total EA spending and performance index

The findings can be stated relatively simply. Correlating overall spending, spending on registration activities, and spending on election practicalities individually with the index of electoral integrity demonstrates that there is a positive relationship between each of these aspects of election spending and increased election quality. The effects are not especially strong, but they are all statistically significant. Figure 1 provides a graphical demonstration of this relationship, taking all aspects of electoral administrative spending together. In short, the more spent, the higher the local authority running the elections performed.

A more complex analysis which attempted to control for additional issues – the type of the council administration, the region the Returning Officer operated in, and some socio-economic and demographic factors – broadly confirmed these findings. Even taking these additional factors into account, greater levels of overall spending (registration and practicalities combined) led to a gradual increase in levels of electoral integrity. In other words, spending on elections did lead to positive, gradual increases in levels of electoral integrity. In two of the models tested, these relationships were statistically significant. Curiously, however, when both spending on the practical aspects of elections and also on registration activities were disaggregated, it is spending on registration activities that appeared to have more of an impact upon electoral integrity in 2009. This was statistically significant across all three models tested.

These are important, albeit tentative, findings. They are tentative because they need to be confirmed with additional data, and under different circumstances – a national general election for instance. They are nevertheless important as they begin to put some hard evidence behind often made assertions that more spending on election administration would improve election quality. While such improvements may only be incremental, as this research suggests, the simple message is that, even in an era of austerity, elections need to be properly funded to ensure that electors’ voices are heard through the ballot box.

The full reference to the research discussed in this blog post is:

Clark, A. (2014) ‘Investing in Electoral Management’ in P. Norris, R. Frank & F. Martinez I Coma (eds.) Advancing Electoral Integrity, New York: Oxford University Press, pp165-188.