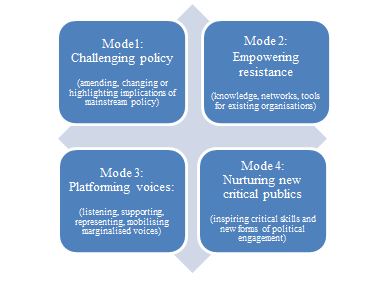

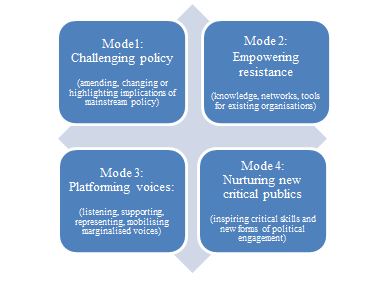

Ahead of REF 2021, Ruth Machen considers what impact from critical research could look like and how assessment frameworks could support, rather than squeeze out, space for critical research. Four modes of critical research impact are outlined: challenging policy; empowering resistances; platforming voices; and nurturing new critical publics. Note that this was originally published on the LSE Impact Blog.

Critical research is often impassioned by a desire for social change. Yet as research that challenges the status quo – by unpacking the socio-historical contingency of meanings and exposing the reproduction of structural inequalities of power – critical research often faces a more challenging pathway to impact. As demands for demonstrating impact are increasingly woven throughout the funding and institutional architectures of higher education, Smith and Stewart are not alone in raising concerns that the impact agenda could adversely affect critical and blue-skies research, favouring instead research that lends itself more easily to societal uptake.

With the draft guidelines for REF2021 open for consultation, now, perhaps more than ever, is a good moment to think about what impact from critical research could look like. And how assessment frameworks could support, rather than squeeze out, space for critical research. To this end, this post outlines four modes of critical research impact: challenging policy; empowering resistances; platforming voices; and nurturing new critical publics.

Research impact: to engage or not?

Anxiety around the impact agenda arises from the increasing instrumentalisation of knowledge, the corporatisation of UK higher education, and the relationship between assessment metrics and neoliberalism (Pain et al. 2011, Pain 2014, Gregson et al. 2012, Olssen 2015). As well as fears that impact will prioritise certain kinds of knowledge, there are also concerns it rewards particular types of researcher; academic elites with established reputations and influential networks rather than early-career or international researchers (Smith and Stewart 2016). These are vitally important concerns. Yet some scholars also identify opportunities for “doing impact differently”. Participatory Action Research (PAR) had delivered social benefits through collaboration with non-academic partners long before research impact became instrumentalised within academic assessments (Pain et al. 2011). Pain in particular seeks to reclaim impact as “walking together”, rather than “striking a blow” (2014; see also Evans 2016). Likewise, Reed and Chubb suggest that impact is a provocation to reconsider our intrinsic motivations for research and epistemic responsibilities. Re-engaging with these, they argue, incentivises impact without research becoming driven by external incentives (Reed and Chubb 2018). Perhaps there is merit in heeding Back’s argument that, as soon as someone suggests “this would make a good impact case study”, we should be alert to how our attention is being directed. However, does pursuing impact necessarily put us, as Back (2015) suggests, “on the side of the powerful”?

Exempting Laing et al’s recent work in education (2018), there is a strange silence around what impact in critical research might look like beyond PAR. Suggestions that not all research, and not all researchers, need to realise impact open space for critical research only through exception, negation, or omission. Instead, building from Pain et al.’s emphasis on the “political imperative to restate the kind of academy in which we want to work” (2011:187), I focus on how impact might be pursued in ways that support and enrich critical agendas.

What might critical research impact look like?

A review of the REF2014 impact case studies yields the following simple typology, which might provide a useful starting point:

Figure 1: four possible modes of critical research impact

Figure 1: four possible modes of critical research impact

Mode 1: Challenging policy

The UK Government Magenta Book – the UK Government’s guidance for policy evaluation – in principle endorses the need for critical approaches that unpack assumptions underlying policy and analyses. Confronting mainstream policy head-on could involve policy amendments by highlighting the implications of existing policies on particular underrepresented groups, geographies, or concerns. More transformative policy change is likely to involve election manifesto writers and/or targeted social pressure rather than consultations within existing policy cycles.

Mode 2: Empowering resistance

Greater traction around critical research findings is sometimes found amongst activist organisations with a degree of policy standing. For these organisations, research, or the connections it articulates, may help to strengthen their discursive position or alternative vision.

Mode 3: Platforming voices

This mode is typified by PAR, where working with marginalised communities often co-produces research questions around non-academic challenges, foregrounds and empowers underrepresented voices, and sometimes challenges participant narratives through deliberation (see Roberts and Escobar’s work on citizen juries).

Mode 4: Nurturing new critical publics

Critical research can inspire new critically engaged citizens. Gregson et al. (2012) argue that engaging with schools can “reclaim critical praxis and constitute new critical subjects”. With rapidly developing digital technologies and the growing role of social media in generating critical publics, there are opportunities to think about new forms of media through which critical publics become fashioned, politically engaged, and/or mobilised.

Recommendations for supporting critical research impact

To support and encourage critical forms of research in the pursuit of societal change, assessments of research impact should bear in mind the following:

- Direct policy citation of critical research is rare. Change is more likely through political ownership of ideas, and what Pain et al. have called a “more diverse and porous series of smaller transformative actions that arise through changed understanding among all of those involved” (2011: 187). Retaining a strong focus on narratives in impact assessment and recognising the role played by relationships are both important.

- Changing the terms of debate is difficult and slow, with quick wins unlikely. Critical research impact may require longer timeframes to develop, materialising outside or cross-cutting assessment periods.

- Marginal/alternative organisations may be smaller and/or more local in reach. Assessing significance and reach together helps to prevent reach from dominating.

The typology presented here is basic, provisional, and by no means exhaustive. Its goal is to prompt debate and expand possibilities for thinking about critical research impact. With similar conversations reportedly held at Open (2013), Bristol (2013), and Glasgow (2015) universities, it would be great to hear more about these discussion findings – especially in thinking through forms of impact beyond policy

Ruth Machen is a Research Fellow at Newcastle University. Her research on science-policy interaction focuses on environmental knowledge where her recent work takes a critical look at science-policy translation – Towards a Critical Politics of Translation

Figure 1: four possible modes of critical research impact

Figure 1: four possible modes of critical research impact