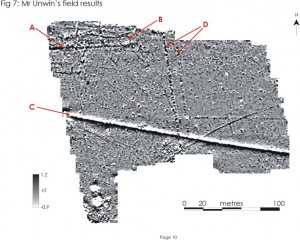

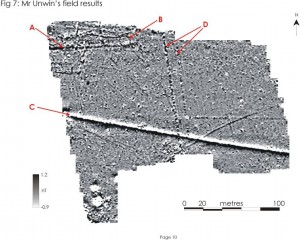

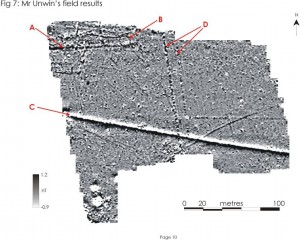

In 2012 we carried out a three week excavation to investigate geophysical anomalies identified in Mr Unwin’s Field. One of these anomalies was circular (B on the graphic below) and such features are usually termed ‘ring-ditches‘, the other was a linear anomaly that was likely to be a ditch (A on the graphic below). The excavation was designed to work out whether the ring-ditch was a part of a burial mound or a prehistoric house and whether it came before or after the ditch.

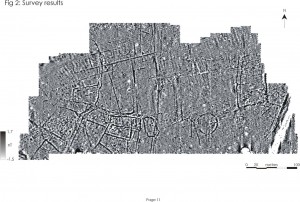

Geophysics of Mr Unwin's Field © GeoFlo and The Lufton Project

The trench was laid out as a 10m x 10m square and excavated by hand. We started by removing the turf and then, in what was about the only hot and dry week of the Summer, we started excavating.

Cutting the turf © The Lufton Project

We removed ploughsoil and subsoil to a depth of about 0.4m. If a cubic metre of sand weighs about a tonne, we shifted about 40tonnes of spoil by hand! At 40cm deep we were on top of a layer archaeologists call ‘the natural’. This is a geological deposit (in our case a nasty clay) that pre-dates all human activity. Cut into the natural were some features. These included the ditch and arc of the ring-ditch we were looking for. These features were filled with a slightly darker and moister sediment than the surrounding natural and are visible in the following photos as dark stains.

Newcastle Students Kate and Ellie along with local volunteers Pete and Robin have found the ring ditch (visible as a dark arc in the deepest part of the trench). © The Lufton Project

The week was really dry and by the end of it the clay had baked hard. The dried out features had all but disappeared from view. We prayed for rain…

Brown, brown and brown. The trench has dried out and the archaeology's invisible © The Lufton Project