In this Lug post, Dr Liz O’Donnell reflects on interviews that she conducted being reused and repurposed for a radio drama, considering the attachments that we as oral historians have to the data we collect.

In October 2016, Radio Four’s Woman’s Hour broadcast ‘Stannington’, a drama in five parts in their ‘Writing the Century’ strand. The writer, Margaret Wilkinson (formerly senior lecturer in prose and script writing at Newcastle University), had developed the play using the archives of a children’s TB sanatorium in Northumberland, and it was gratifying to read that, as well as ‘the amazing photos, x-rays, patient notes, letters, and an original Matron’s Journal 1908-1914’, she was ‘particularly inspired… by the oral histories in the form of interviews transcribed in 2013, from former patients and staff’ (read more here).

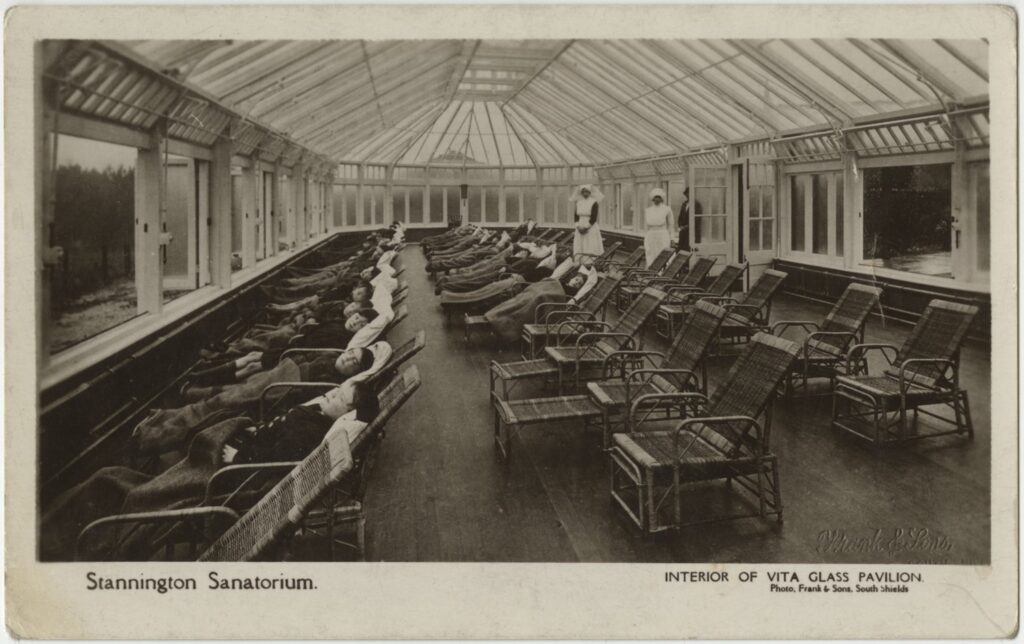

Between March and October 2013, those interviews – of almost 30 former patients and staff members – had been conducted by me, on behalf of Northumberland Archives. Stannington Sanatorium opened in 1907, the first in this country dedicated solely to the care of children suffering from tuberculosis. Its patient records, all 120 linear feet of them, deposited in the archives in the mid-1980s, had never been fully catalogued, therefore remaining largely closed to researchers. To secure the preservation and accessibility of this unique collection, an application for a major Wellcome Trust grant was underway and the oral history project would feed into the application process. Crucially, the interviews would capture the memories of those who, suffering from a deadly disease before the availability of any effective medication, had experienced lengthy hospitalisation in childhood, profoundly affecting their lives.

The project was one of the most rewarding I ever undertook. The memories dated from the 1920s to the early 1950s, and inevitably strong emotions were stirred up. There was fear (eating food after it had been vomited on to avoid being told off), unimaginable homesickness (pre-war, parental visits were only allowed for two hours once every two months), and acute physical discomfort (being encased in plaster or stretched on frames to prevent distortion of joints affected by tuberculosis). Separation from family could last for years (seven in the most extreme case) so that, returning home, the children felt like strangers, stigmatised for contracting the disease (instructed by her mother never to mention the sanatorium, one woman had not spoken about her stay there for over sixty years). Who could fail to be moved by these vivid stories of misery, stoicism and resilience?

It was a strange feeling, listening to anecdotes I remembered having gathered from real people, re-presented in a different context, and hearing thoughts they had shared with me put into the mouths of imaginary characters. The drama juxtaposed fact and fiction, with dramatized scenes bookended by the reminiscences of a 17 year old student nurse, Marjorie (originally interviewed by me), who worked at Stannington in 1949. The other characters seemed to have been fashioned from anecdotes I recognised from different interviews, along with pure invention.

Shortly after its broadcast, I heard of a former patient at the sanatorium who, on hearing the drama, had broken down and wept, as powerful memories of his time there resurfaced. It was clear that writers of fiction may convey the past more effectively than any historian, especially when exploring feelings of the interviewee experienced in childhood.

So did it matter that events had not actually happened as they were portrayed, that living people had been turned into characters, the more colourful aspects of their testimony mined for dramatic effect?

A vague sense of unease centring on these questions has led me, over the years, to see what others have said about re-purposing oral history interviews as fiction.

Ariella Van Luyn argues that transparency – ensuring participants are clear about the intention to fictionalise material, even though this may affect what they choose to tell and the way they tell it – is essential. For her, conducting her own interviews, ‘oral histories are not valued so much for their factual content but as sources that are at once dynamic, emotionally authentic and open to a multiplicity of interpretations.’ The Sugar Girls project, led by Duncan Barrett, also generated its own source material, gathering highly personal stories of female workers in sugar factories in London’s east end, before using literary techniques to produce what Barrett calls ‘creative’ or narrative non-fiction (Barrett: 2012).

Helen Foster, on the other hand, works with extracts from extant oral histories. A curator of digital archives with Historic Environment Scotland, she is all too conscious of the tens of thousands of oral history interviews that are never listened to, and looks for new ways to present the material to diverse audiences. Describing herself as an ‘eavesdropper…a third party to an exchange between interviewer and narrator’… ‘simply listening in…[as if to] an interesting exchange between two strangers on a bus’’, Foster immerses herself in the words to produce poetic responses to the imagery, drama, and silences she finds. Sometimes this might take the form of ethnopoetics, a transcription style drawing on poetic and script conventions to present the words on the page, using line breaks to mirror the fluidity of speech patterns.

My reaction to the Stannington drama was, I know, coloured not only by an intimate connection with the sources used in its development, but also by over forty years of applying a strict regime of accurate attribution and fidelity to any historical evidence used in my work. And yet I am aware that oral history interviews are in fact artificial constructs, not least because the presence of the interviewer undoubtedly shapes the outcome. Moreover, I am no stranger to deploying oral histories to convey a historical period as vividly as possible, in order to engage public interest. The 2009 exhibition I worked on at Woodhorn Museum, Ashington, Northumberland, about the experiences of non-combatants during the Second World War, was based almost entirely on the oral testimony of dozens of interviewees, covering every aspect of the home front, from evacuation, land girls and Bevin Boys to a German POW. Could I, by using individual memories to illustrate different types of experience, be accused of fabrication?

Wilkinson, explaining her creative process, describes memories as fluid, ever-changing, allowing different versions of the same story to co-exist. (Wilkinson: 2016) Re-interviewing the student nurse at the centre of the drama, she realised that Marjorie’s idealised recollections – dances at the lovely nurses’ home with its grand piano in the sitting-room, the hard yet satisfying work to keep the young patients clean, fed and free of bed-sores – were often challenged by the children’s own memories and by written sources like the matron’s journal, all portraying a less rosy picture of life in the sanatorium. This contradiction provided Wilkinson with the drama’s structure, the nurse’s reminiscences (almost verbatim, but ‘mediated by the writer in the interests of drama’) being interspersed with scenes revealing a different version of sanatorium life. In this way, by opening ‘the gaps between the told story and the dramatized story’, she could explore memory and its failures, all the while holding an audience’s attention.

And so I have more understanding of the appropriation of ‘my’ interviews for dramatic purposes. Part of my work at Northumberland Archives had involved publicising their impressive oral history collection, showing how the resource – with hundreds of interviews dating back to the early 1970s – could be reused, precisely as suggested by these insights into different creative formats. The richness of the Stannington resource is underlined by a recent collaboration between Deborah Ballin (Leeds Arts University) and Dr Janice Haigh (Sheffield Hallam) in a multi-disciplinary project, ‘Under an Artificial Sun’, based on the collection, using new and existing oral history testimony and archival material to explore the impact of hospitalisation in childhood, including through imaginative techniques. And after all, as Wilkinson writes, ‘without our intervention…the archive…sits in silence.’

Further Reading:

Barrett, Duncan, ‘Oral History and Creative Non-Fiction: Telling the Lives of the Sugar Girls’, in History at Large, 11 March 2012 https://www.historyworkshop.org.uk/oral-history-creative-non-fiction-telling-the-lives-of-the-sugar-girls/ (accessed March 2022).

Foster, Helen, ‘Finding poetry in the sound archives: creatively repurposing oral histories for re-presentation and engagement’, in Oral History, Spring 2018, pp.111-117

Morrissey, Charles T, ‘Oral History and the Boundaries of Fiction’, in The Public Historian, 7:2 (Spring 1985), pp. 41-46

Northumberland Archives, Stannington (online exhibition), https://northumberlandarchives.com/exhibitions/stannington/index.html (accessed March 2022)

Sutherland, Neil, ‘When you listen to the winds of childhood, how much can you believe?’, in Curriculum Inquiry 22:3 (1992), pp.235-255

Van Luyn, Ariella, ‘An obsession with storytelling: Conducting oral history interviews for creative writing’, Ejournalist, 11:1, June 2011, pp. 29-44 https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/303750334.pdf (accessed March 2022), p.35

Margaret Wilkinson, ‘Exhumation: How Creative Writers Use and Develop Material from an Archive’ Newcastle University (November 2016). http://theses.ncl.ac.uk/jspui/handle/10443/3531 (accessed March 2022)