A few months ago, Special Collections at Newcastle University were contacted by one of the original members of the expedition team of the 1965 expedition to Afghanistan. Howard Horsley asked if we would be interested in taking a donation of items relating to arrangements, reports, and the activities that took place during their time completing the scientific study.

Special Collections already holds a significant number of expedition reports completed by the University Exploration Society. The Society was inspired and encouraged by Dr Hal Lister of the Geography Department and its expeditions were largely student and postgraduate led. We also hold a significant amount of archive material relating to the British North Greenland Expedition on which Dr Lister was the Chief Glaciologist.

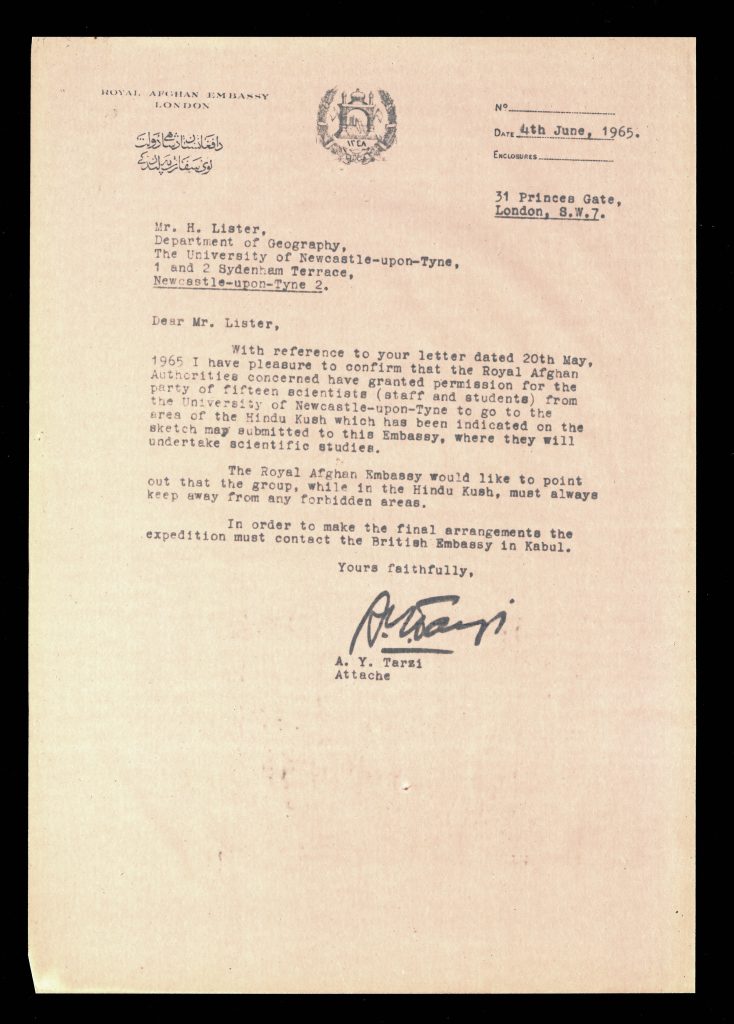

The expedition, which Howard was prepared to donate information, was significantly different in scale and aspirations. This was an expedition that was university staff led and directly sponsored by Newcastle University. It was planned in the first year of independence from the University of Durham and was inter-disciplinary, aiming to support the research of the International Hydrological Decade. Major financial contributions to the expedition were given by institutions such as the Royal Geographical Society and Mount Everest Foundation.

The reason for such widespread support for the expedition was its broad scientific aims, including its central focus on climate change and specifically upon the exploration of whether Dr Lister’s earlier observations of glacial retreat in both Greenland and Antarctica was replicated in the glaciers of the world’s highest mountains.

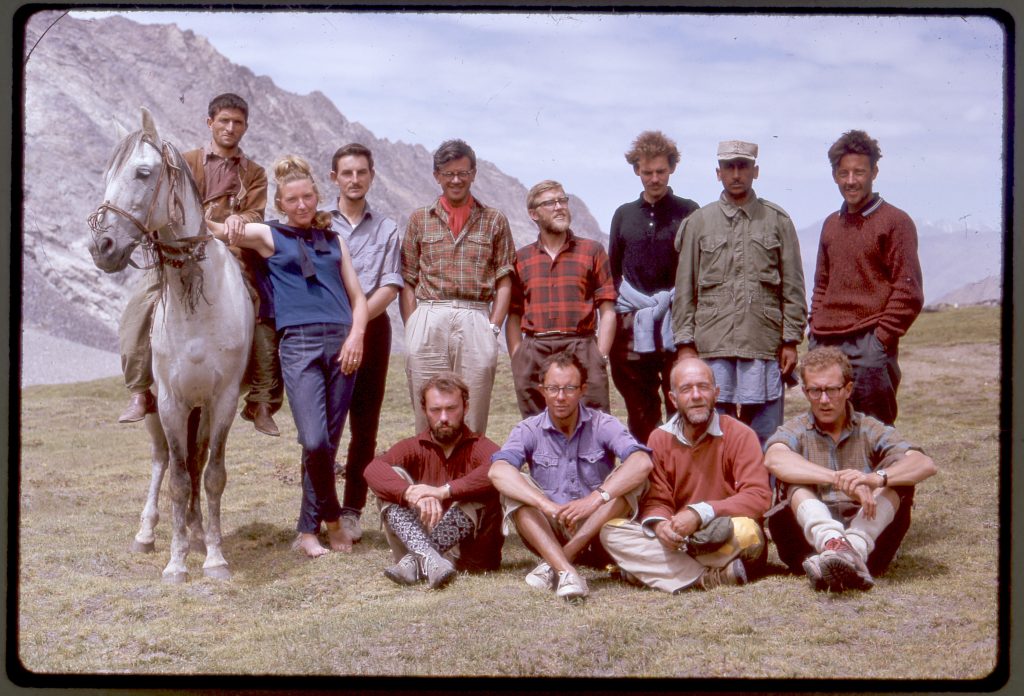

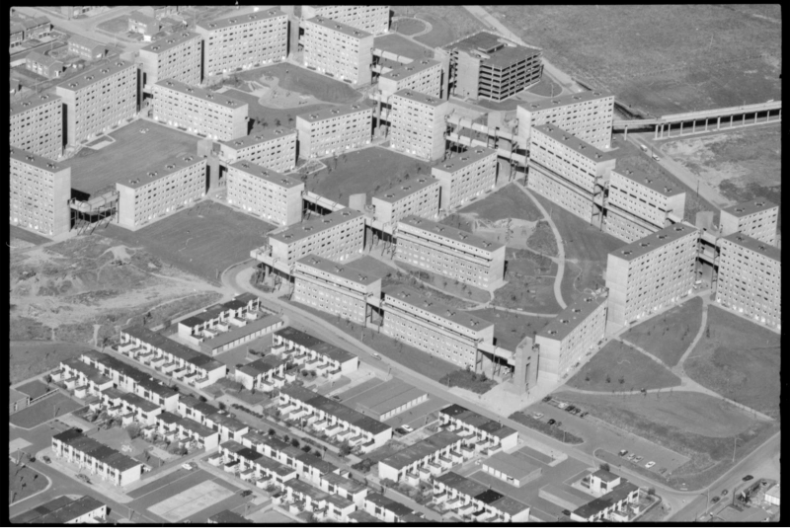

The Expedition was originally planned to take place in the Chitral region of Pakistan, close to the point at which the Hindu Kush, the Karakoram and the Himalayan ranges meet, a region with more glacial ice than anywhere other than Antarctica and Greenland. Due to the outbreak of war between Pakistan and India, last minute location changes had to be made. The expedition was redirected to Afghanistan as an alternative focus for research. Eminent interdisciplinary academic staff were supplemented by others with a wealth of climbing experience to ensure a safe working environment. Two undergraduates, one of whom was Howard Horsley, were also included within this team.

The main aim of the expedition was to investigate the heat and water balance of the tropical glaciers and discover whether they display the same evidence of climate change of that of the ice sheets in North Greenland and the Antarctic, as noted by Hal Lister.

The importance of the expedition was, therefore, in establishing that the temperature balance of montane glaciers seemed to display the same evidence of climatic warming as polar ice sheets. This was almost certainly the first scientifically validated evidence of the universality of climate change and its warming affecting glaciers. In 1965 key findings were regarded as not being of wider validity and thus of no more than theoretical importance. The potential wider implications were not immediately recognised, and no follow-up expedition was envisaged.

But, In the intervening decades the evidence stacked up that glacier recession is taking place and is caused by a warming planet. The alarming implications of this glacial recession are now becoming all too obvious and threatening.

The BBC have recently reported the worsening floods in Pakistan caused by climate change. It is believed that the origin of the present flooding is firmly rooted in the area in which this original expedition took place. The issue is, however, a problem all over the Hindu Kush and other surrounding tropic locations. More information can be found on the BBC News.

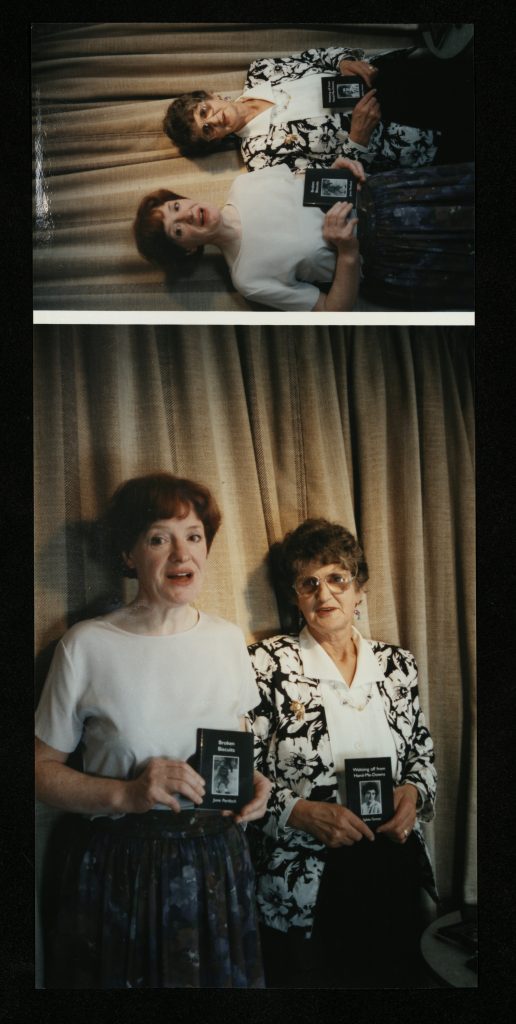

The archive we now hold shows a fascinating personal look into the expedition and includes Howard’s diaries; letters home and painstakingly researched biographies of the members of the team. There are instances of generators breaking, wheels falling off trucks and Cholera. There are beautiful negatives of stunning countryside and wonderful culture; a few of which are shown in this blog.

If you are interested in expeditions, global warming, geography, culture, history or even just would like to learn about the travels of a past university student, this is the archive to request to view!

It is with great thanks to Howard for gifting the university this wonderful personal and professional archive and taking the time and effort to create the individual biographies of the team members. Without his wealth of knowledge, the information may have been unavailable for future generations.

The archive includes but is not limited to:

- A land utilisation survey of the village of Kejuan in the upper Panjshir Valley Afghanistan, Carried out during July 1965. Dissertation submitted by H. G. Horsley 1965.

- Reflections on the geography of Afghanistan. H. G. Horsley.

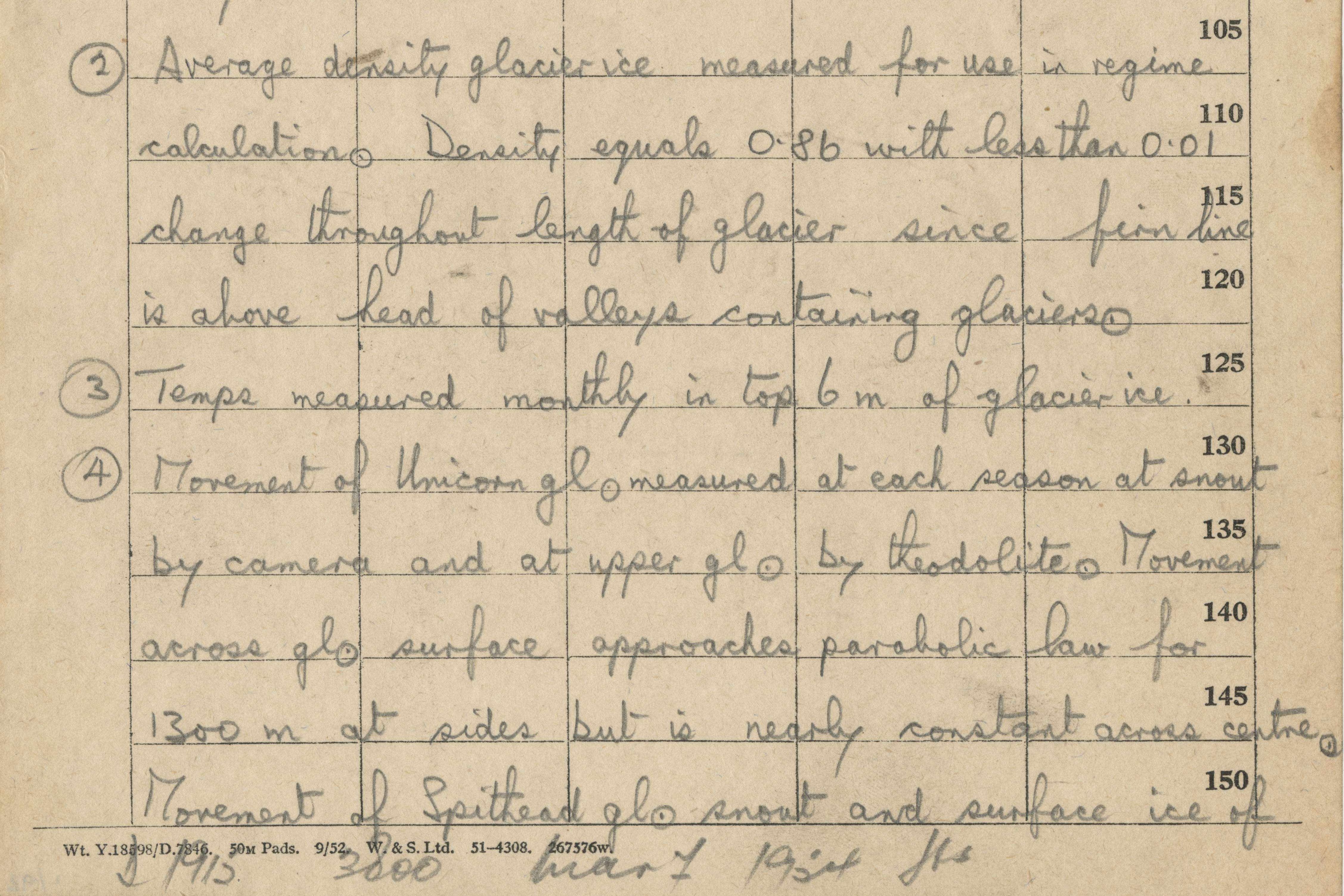

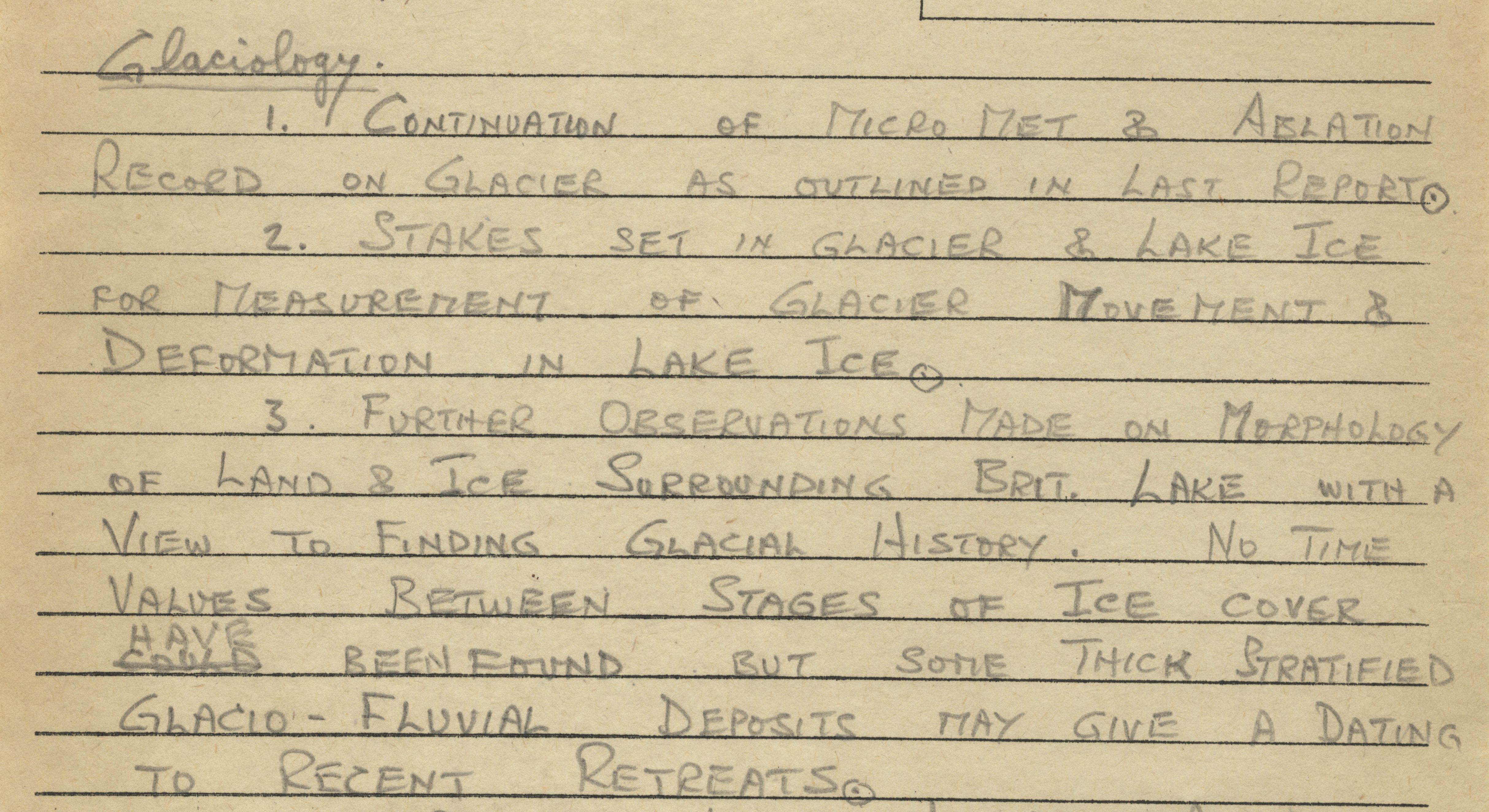

- Newcastle University Expedition to Afghanistan Preliminary Report.

- Environmental Research in the Samir Valley of the Hindu Kush, Afghanistan. Summary Report by Newcastle University. May 1966.

- Environmental research in the Samir Valley of the Hindu Kush, Afghanistan. Final Technical Report by Newcastle University. June 1968. Editor A. James.

- Kabul Times. Vol IV. No 88. Thursday July 8, 1965. (Newspaper sheet).

- File – Karakoram Expedition, Chitral Expedition, Map of Chitral area, Chitral Expedition further information, University of Newcastle expedition to Northwest Pakistan, Equipment list, Letter to Mr Horsley, Chitral expedition completion information, correspondence, equipment lists, expedition fund contributions, Immunisation programmes, Visa requirements, embassy acceptance to carry out scientific research, micrometeorology.

- Preliminary Hydrology report.

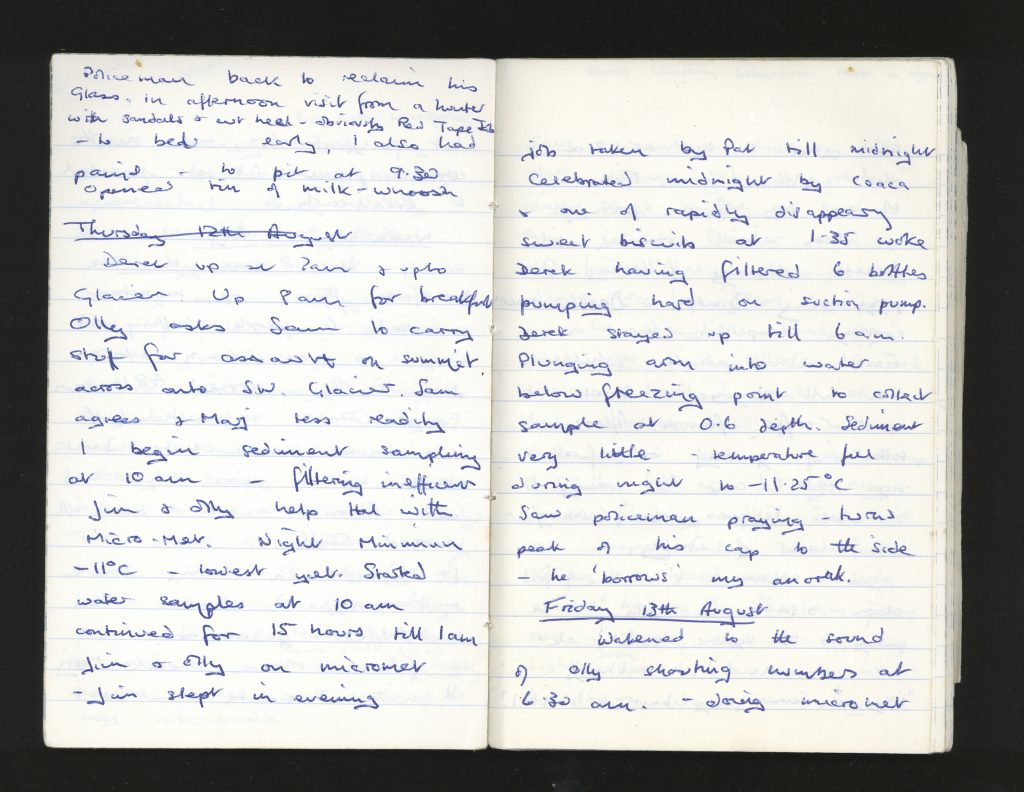

- 1965 expedition journals written by Howard.

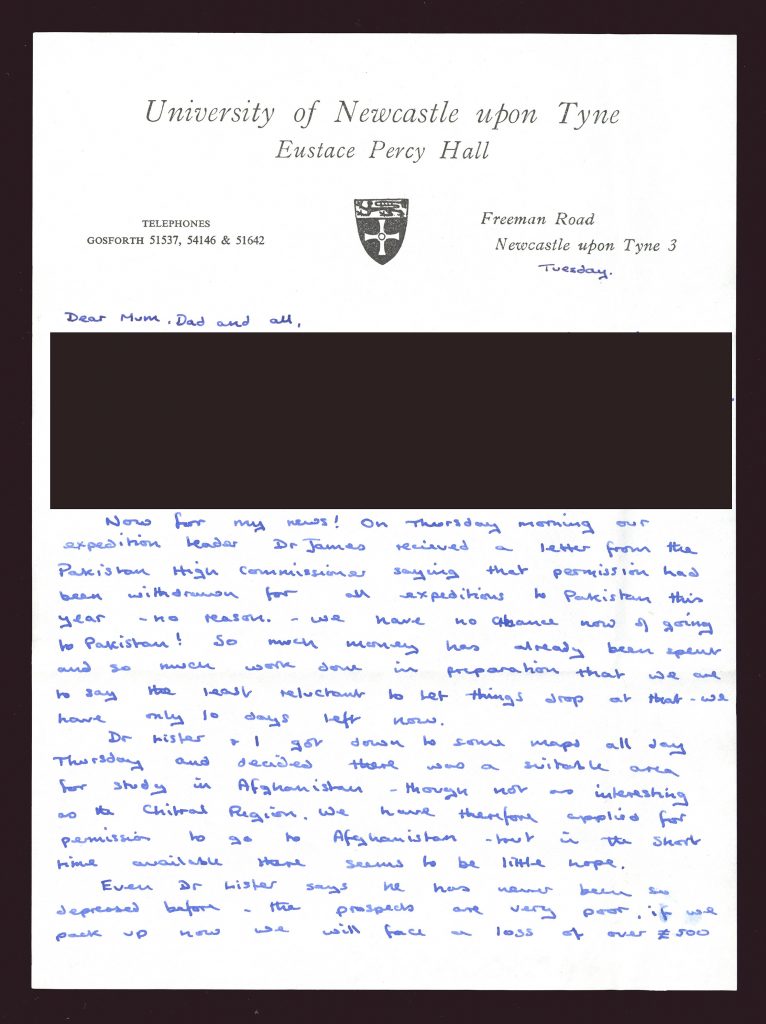

- Personal letters between Howard Horsely and parents which give context around the change in plans of expedition locations.

- Correspondence regarding a broken generator on site.

- Biographies on Margery James, Howard Horsley, Sam James, Dr Pat Hurley, Dr Oliver Gilbert, Derek Jamieson, David Beynon, and Hal Lister.

- Expedition to Afghanistan photobook.

- Negatives and slides depicting the expedition before are currently being updated and will be available on Collections Captured.

![Back cover of: Carletti, Angelo. Summa Angelica de casibus conscientie cum additionib[us] nouiter additis (Nurenberge: Impressa per Antonium Koberger, 1498)](https://blogs.ncl.ac.uk/speccoll/files/2025/07/Sandes-259-Back2-784x1024.jpg)

![Ticket proofs for performance of All our Yester-Gays by the Consenting Adults in Public theatre company in Newcastle, 12 August [1976?]](https://blogs.ncl.ac.uk/speccoll/files/2025/06/CHE-01-05-3-crop-752x1024.jpg)