The Englishwoman’s Domestic Magazine was a pioneering monthly publication aimed at young, middle-class women in the mid-Nineteenth Century. From 1852 to 1865, it had been edited by Isabella Mary Beeton and her husband, Samuel Orchart Beeton. When Isabella died, her friend Matilda Brown stepped in as co-editor and publication continued until 1879.

The periodical had sections including domestic management, embroidery, serialised fiction, translations of French novels, and unusually, it featured dress-making patterns. A boom in the sewing machine industry in the late 1850s and 1860s gave rise to the first ready-to-wear clothes, and the development of sewing machine models for the domestic market. In the 1860s, sewing machines were not uncommon in middle-class homes.

The Englishwoman’s Domestic Magazine was also ahead of its time because it solicited correspondence and contributions from its readers, which were responded to in a section called ‘The Englishwoman’s Conversazione’. Here, were laid out wide-ranging anxieties, from the “over-stocked” governess market to how to make a curry, and from romantic entanglements (reply to‘A Well-wisher’:“Marriage with a deceased husband’s brother is illegal.”, July 1866, p.224) to membership of The Society for Promoting the Employment of Women. Some of the women that wrote in gave their names; others gave only their initials; and yet others wrote under a pseudonym.

There is evidence in the conversazione of women taking an interest in textiles and fashion. A reply to ‘Queechy’ suggests ways in which scraps of material may be utilised:

“Your fragments might be made up into pincushions or similar articles for the toilet-table; they might serve as ribbons to boot-makers, etc. There are endless ways of using up such material into little articles saleable at a bazaar” (January 1866, p.32).

‘An Old Subscriber’ wanted to know why men complain about hoops and crinolines and verse from a newspaper was transcribed by way of a response (March 1866, p.96):

“When men deride the ladies’ dress

And say they’re like balloons,

But think not of their bearded selves,

Their likeness to baboons –

If I a lady might advise

(Although it should amaze her),

I’d say, ‘If we put down our hoops,

Will you take up the razor?’”

Jessamy Bride asked, “is it right for bridesmaids to go to church with bonnets on, as they did at Kew?” (August 1866, p.256). The editors thought it entirely appropriate, being “simpler and much more natural”. (On 12th June 1866, Princess Adelaide Hanover had married Francis Teck at St. Anne’s Church, Kew.) And in December 1866 (p.384), Clara sought advice on the best way to style her hair and clothe herself based on the description that she is “tall, having rather a round face, and not very good nose”.

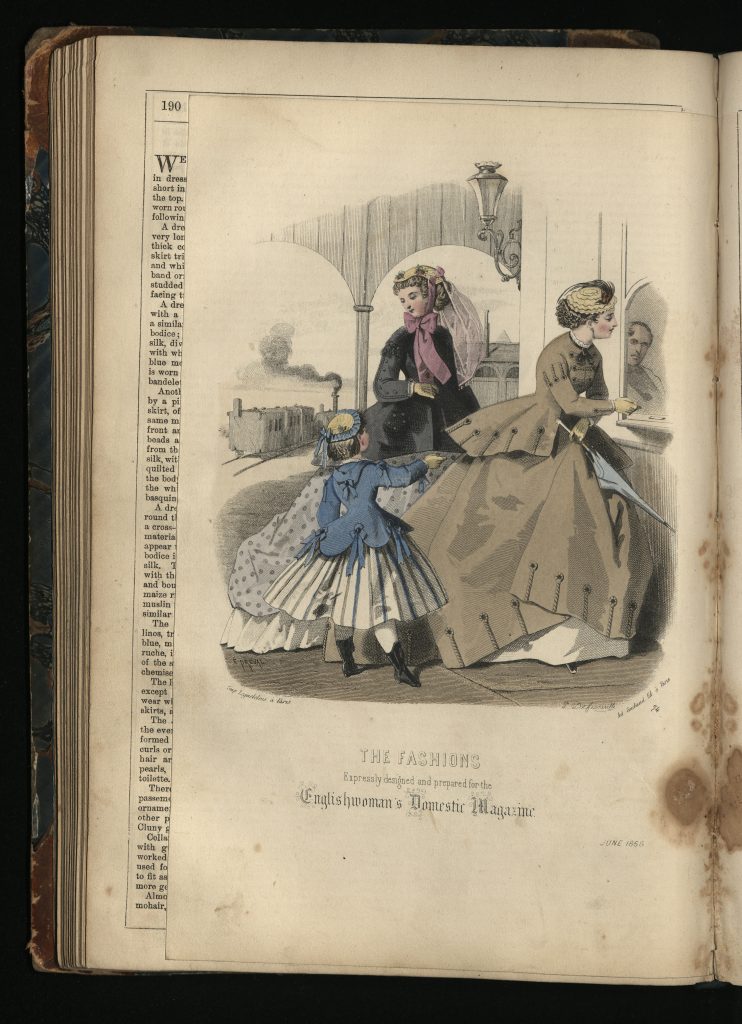

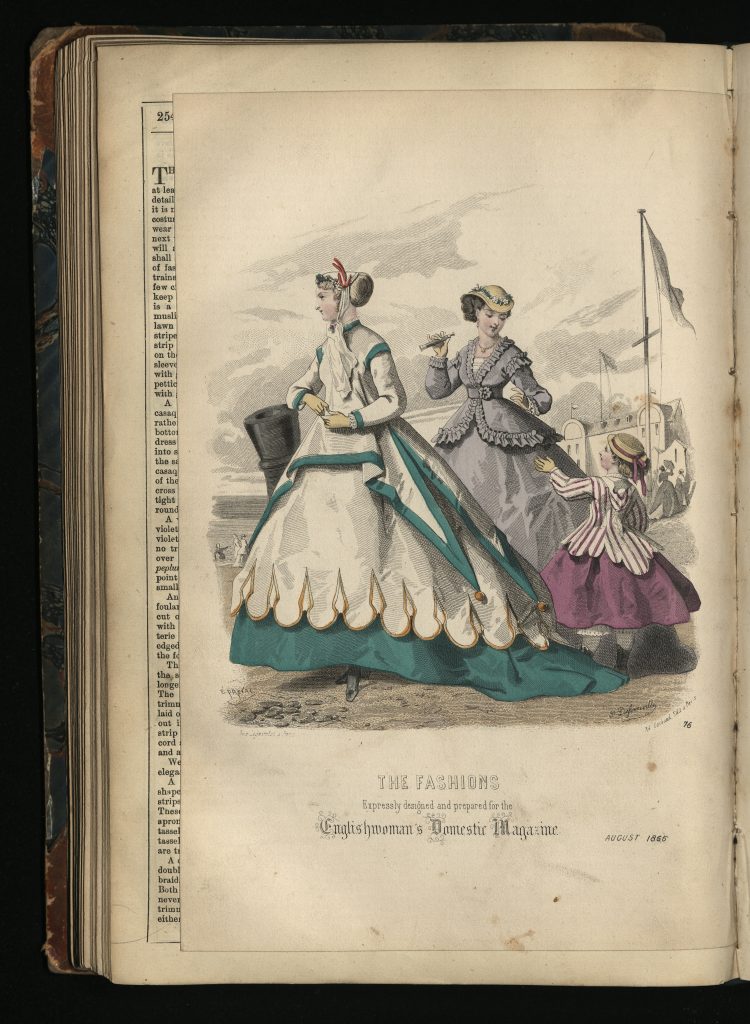

From 1860, the Englishwoman’s Domestic Magazine featured high-quality hand-coloured fashion plates, imported from Paris, making it a valuable resource for fashionably dressed ladies. The purposes of the fashion plates then were the same as today: to communicate information about the current trends and to create a receptive audience for incoming styles. In The Englishwoman’s Domestic Magazine, elegant figures are presented in colour against simple black and white environments, such as a railway station or drawing room.

Fashion is aspirational and symbolic of real or perceived status. The women depicted on these fashion plates attend balls, carry parasols, go to the beach for leisure, go riding or hunting, and wear silks and bonnets trimmed with ribbons and feathers. To paraphrase Doris Langley Moore, they inhabit a charmed world where neither human, beast or fowl suffers pain or cruelty for fashion. [i]

In 1866, crinolines were changing and would be phased out by the end of the year, being superseded by the bustle. Having ballooned beyond all practicality, the front became flatter whilst the back became more voluminous. The shape of the skirts can clearly be seen in the illustration below.

At the same time, there was a transition from pointed bodices to belted dresses. Dresses had double skirts and straight sleeves. Instead of floral decorations, there was a move towards ribbon trimmings.

World events influenced fashion too. The 1860s were a tumultuous decade during which nations and societies were reshaped by wars, including the American Civil War (1861-1865) and the Prussian-Austrian Seven Weeks’ War (1866). Fashion responded to these conflicts with military-style jackets. An example may be seen in the detailing of the girl’s costume in the fashion plate for May 1866: high boots and a silk jacket and skirt trimmed with braid.

The fashion plates sit within a regular section called ‘The Fashions’, which begins with a long description of the season and current looks. January is all about “wrapping oneself up in the soft warm materials suitable to the inclement season”: velvets, silks, and furs. Come February, “glitter is the fureur of the day”: on bonnets, coiffures [i.e. hairstyles], walking and evening dresses, “glitter on every part of a lady’s toilet, from the head-gear to the slipper”. Lingerie is the focus for March for “details often tell more in the tout ensemble of a dress than the dress itself”.

Heading into Spring, the fashionable lady of 1866 was wearing linos [flax] or mohair dresses in grey, dun and fawn. In May, the editors turned attention to the “numerous modifications” that bonnets were subjected to:

“Some of the patterns exhibited this spring in the windows of some of our first modistes are so strange that crowds of curious persons of both sexes are continually seen stopping to examine them”.

Fashion being cyclical, there is then a return to “the fashions of the time of the Empress Josephine” [ii]: a plain, gored [flared, flowing] skirt with low, short-waisted bodice, square neckline and a wide sash tied around the waist and finished in a large bow at the side – what we know as an empire line dress.

The expansion of rail travel affected fashion as people could holiday at the coast, thus thoughts turned to travelling and seaside costumes in July and the colours to be seen in, whether they were suited to the wearer’s complexion or not, were yellow and bright rose. There was little change in Summer but hemlines rose and crinolines were “altogether given up” in favour of “short scant dresses” that didn’t reach beyond the ankle, as seen in the ‘seaside toilet’ worn by the figure on the left in the plate below.

The rise of train travel had also contributed to an increase of environment-specific clothing, for example the shooting season having begun, all concerns in October were for “pretty country costumes, fanciful hats and demi-toilettes for the evening”. Velvet and satin were “profusely employed” by couturiers and “a great deal of taste” was required when it came to matching colours in November. December’s fashion section was dedicated to children.

Included in ‘The Fashions’ was a short sub-section headed ‘India and the colonies’ which spoke to the magazine’s subscribers in India, Canada and other occupied parts of the world. The text is reprinted without any changes each month and is essentially an advertisement for the services of Madame Goubaud who seems to have been based in Europe and able to fulfil requests for dresses, bonnets, hats trimmings and more. Through the column, we learn that the English colonisers continued to be consumers of Parisian and London fashion. Advice given in later issues of The Englishwoman’s Domestic Magazine and other ladies’ periodicals was to adapt fabrics to the climate, and to favour taking haberdashery items rather than fully made-up clothes when relocating abroad.[iii]

[i] Moore, Doris Langley. Fashion through fashion plates 1771-1970 (New York: Clarkson N. Potter, 1971), p.9.

[ii] Josephine Bonaparte (1763-1814) was the first wife of Napoleon.

[iii] Bhamburkar, Tarini. ‘”Crushed Flounces and Broken Feathers”: British Women’s Fashions and their Indian Servants in Victorian India’ in Journal of Victorian Culture Online (November 18, 2021) https://jvc.oup.com/2021/11/18/british-womens-fashions-and-their-indian-servants/, accessed 22/12/2025.

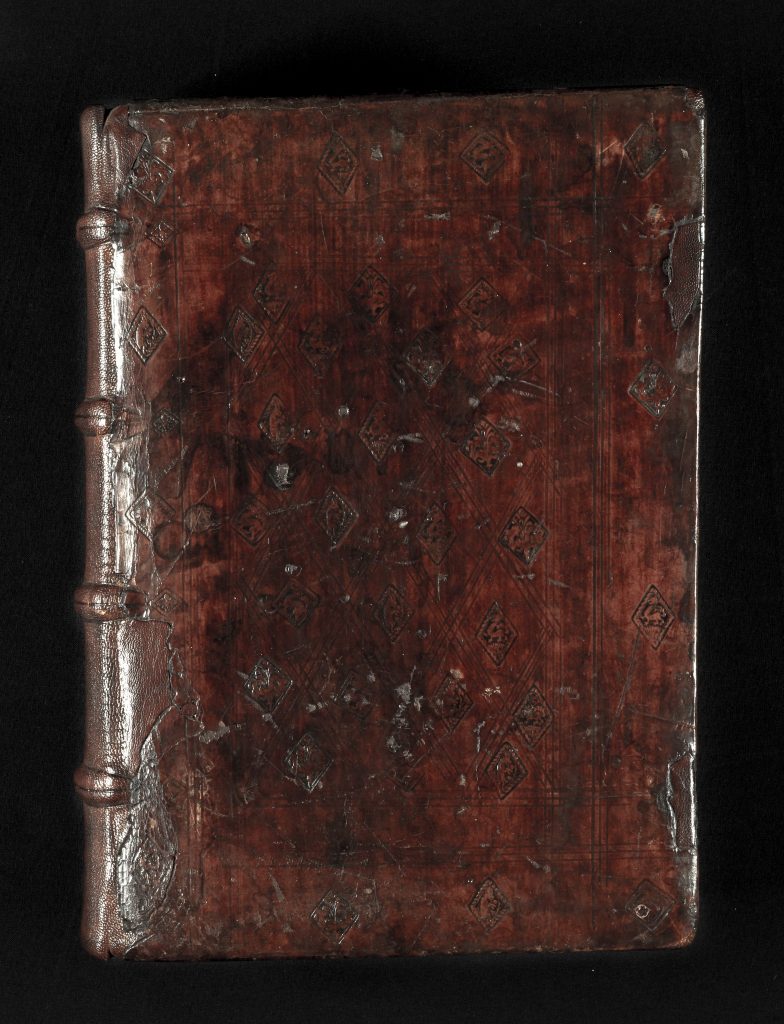

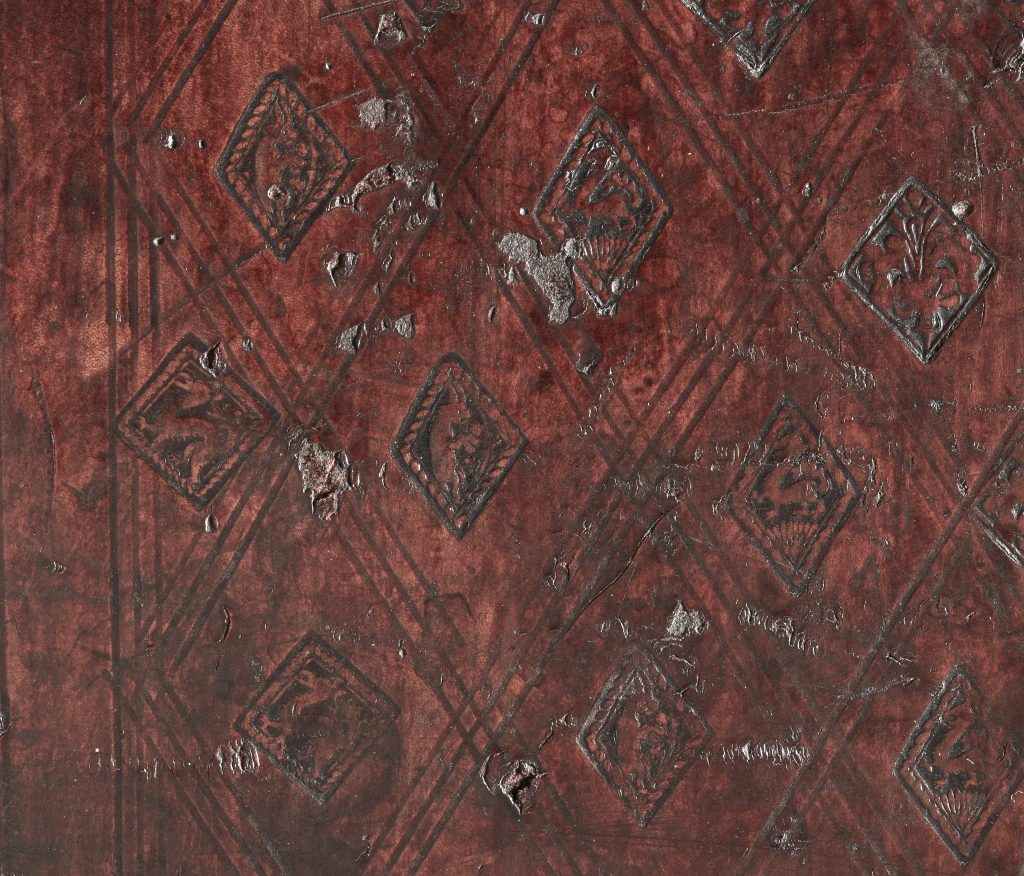

![Back cover of: Carletti, Angelo. Summa Angelica de casibus conscientie cum additionib[us] nouiter additis (Nurenberge: Impressa per Antonium Koberger, 1498)](https://blogs.ncl.ac.uk/speccoll/files/2025/07/Sandes-259-Back2-784x1024.jpg)

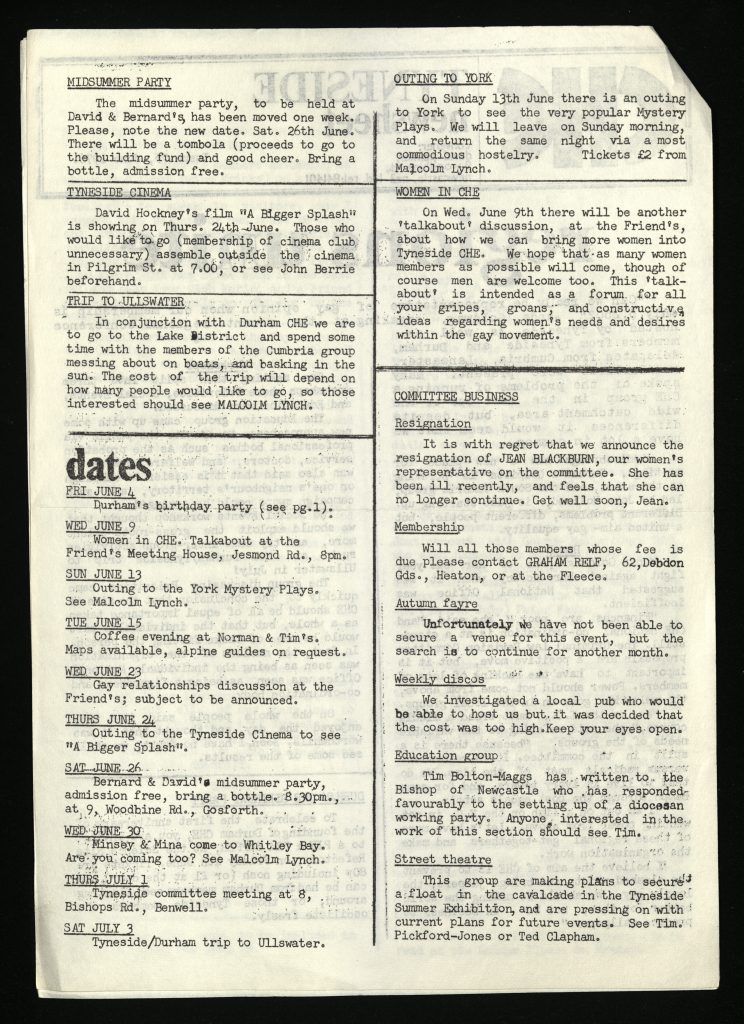

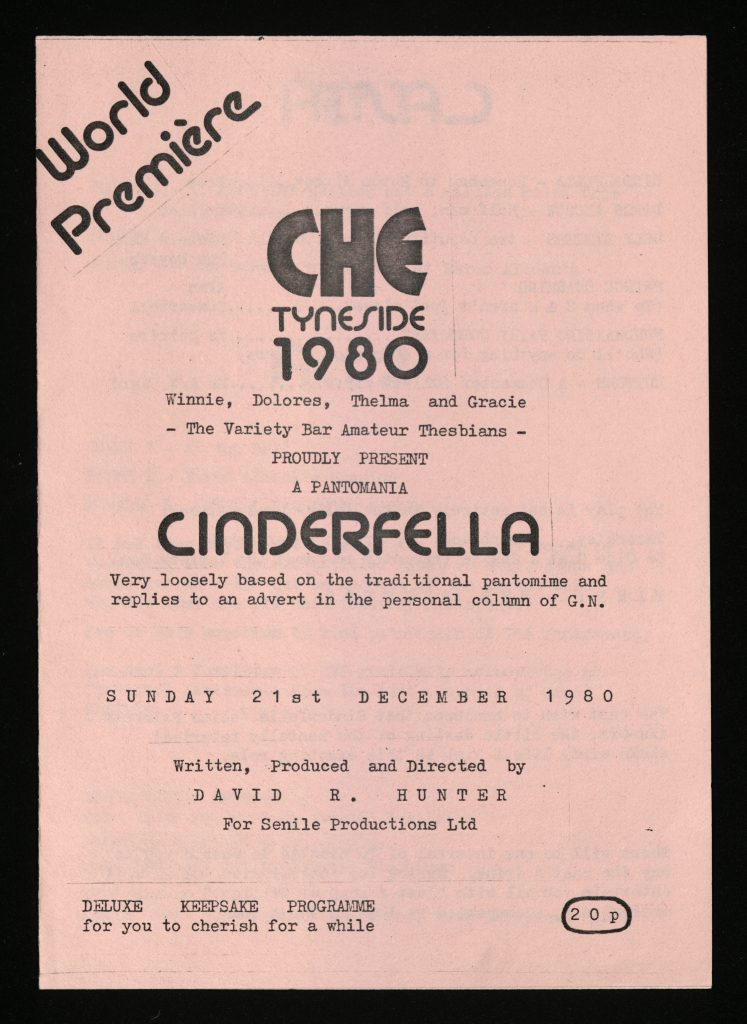

![Ticket proofs for performance of All our Yester-Gays by the Consenting Adults in Public theatre company in Newcastle, 12 August [1976?]](https://blogs.ncl.ac.uk/speccoll/files/2025/06/CHE-01-05-3-crop-752x1024.jpg)