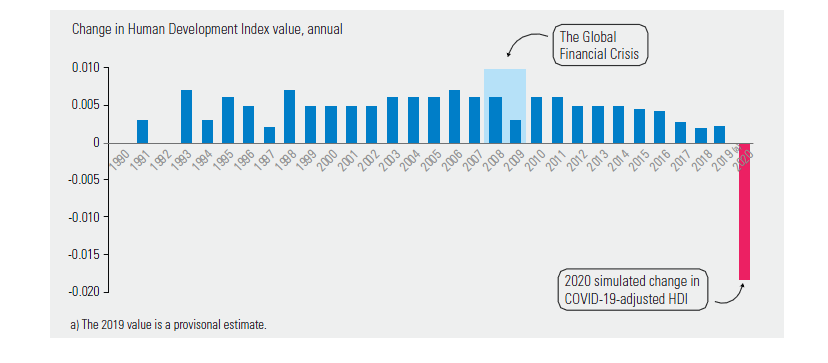

Like many people, I’ve thought about food during lockdown a lot more than usual. Unfortunately, also like many people, the effects on my waistline have not been pretty. But I’ve also done some reading, notably of three documents that are critically important for all of us concerned with health and health inequalities.

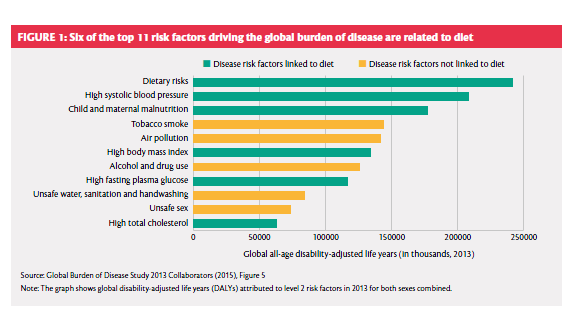

The first of these actually came out in 2016. It’s the report of a London-based Global Panel on Agriculture and Food Systems for Nutrition, funded by the UK’s Department for International Development (DfID); co-chaired by a former president of Ghana and a former Chief Scientific Adviser to the UK government; and supported by what can fairly be called an all-start cast of expert group members, authors and reviewers. It correctly identified the ‘nutrition crisis’ associated with the fact that ‘approximately three billion people from every one of the world’s 193 countries have low-quality diets,’ warning that ‘[t]he risk that poor diets pose to mortality and morbidity is now greater than the combined risks of unsafe sex, alcohol, drug and tobacco use,’ those awful things health promoters always complain that other people are doing. The risk factors being compared are actually a bit of a dog’s dinner, as you can see from the illustration, but that doesn’t alter the basic point.

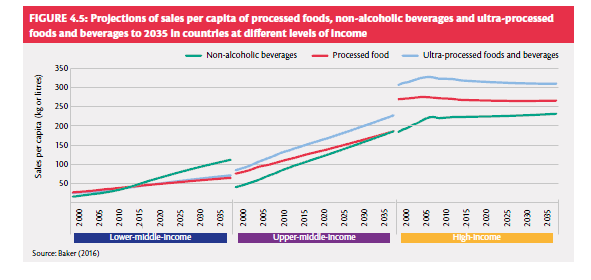

Like the other two documents, it adopts a whole-system perspective on food and nutrition, which is itself a welcome conceptual advance. Also like the other two, it explicitly identifies as a major problem the (un)affordability of healthy diets for many of the world’s people. It points to some worrying trends and prospects in the sales of ultra-processed foods, which are levelling off in the high-income world but climbing elsewhere, especially in upper-middle-income countries, and are projected to continue doing so.

And it warns that: ‘The power and concentration of large agribusinesses, manufacturers and retailers, has grown. This in turn means that power structures in food systems have changed, which not only influences what is produced, but political decision-making’. Perhaps not surprisingly, it’s a bit vague on how to deal with the problem – we have to remind ourselves that Coca-Cola’s annual marketing spend is about twice WHO’s entire annual budget – but as the saying goes, admitting that you have a problem is a first step.

The other two documents actually appeared during lockdown. The first of these is a National Food Strategy for England, written by restauranteur Henry Dimbleby with a somewhat smaller but still impressive supporting cast of food system protagonists and public servants. It offers an in-depth description of how the pandemic affected the UK food system, which is valuable in and of itself, and offers a number of recommendations for food trade policy after the UK leaves the single market at the end of 2020. Guardian food writer Jay Rayner was harshly critical of the report, calling it ‘thin gruel and easy to set to one side’ and saying that the policy recommendations ‘will do little for the millions who go hungry’.

Admittedly, the report is far too sanguine about the value of Parliamentary scrutiny of trade agreements under today’s conditions of elective monarchy, and it doesn’t even mention investor-state dispute settlement provisions or power dynamics that will favour agribusinesses based in our larger, richer trading partners in future negotiations. However, among other strong points the report provides a powerful demolition of arguments against restricting advertising of foods high in fat, sugar and salt, and a similarly effective challenge to the claim that eating healthily is just as affordable as the unhealthy alternative (pernicious folk wisdom that is unsupported by serious research). Perhaps most importantly of all for population health researchers, a valuable warning against the evidence-based policy fetish is worth quoting at length, and framing.

Over the past 30 years, there has been much emphasis on the importance of “evidence-based policymaking”. This sounds eminently sensible; indeed, you might think it the minimum one should strive for. But it has given birth to a new science of “policy evaluation”, which may actually lead to cowardice in policy making.

You can’t always find evidence to support a single policy. An evaluation of one intervention in a huge and complex food system might conclude that the intervention has no effect, because the effect is too small to measure. But the effect is still there, and if you press on with all the little things together, you might end up with a big effect.

….

The other problem with evidence-based policymaking is that it creates a Catch-22. You can’t bring in a policy until you have the evidence to show it works; but you can’t get the evidence without first introducing the policy. In the absence of data, it’s all too easy to end up doing nothing rather than risk unintended consequences.

Dimbleby points to the widely cited Finnish heart disease reduction initiative in North Karelia, quoting its architect Pekka Puska, as an example of what can be done when the Catch-22 is avoided.

Another strong point of the report is its focus on the food security implications of a coming wave of unemployment, given the context in which, ‘[b]efore the pandemic, four in ten working-age people in the UK (almost 17 million people) had less than £100 in savings available to them’. Rayner was correct to say that the report’s recommendations would do little to address this basic problem of inequality, with origins entirely outside the food system and worsened by a decade of unnecessary and macroeconomically counterproductive austerity. Yet here, again, recognising that you have a problem is a first step.

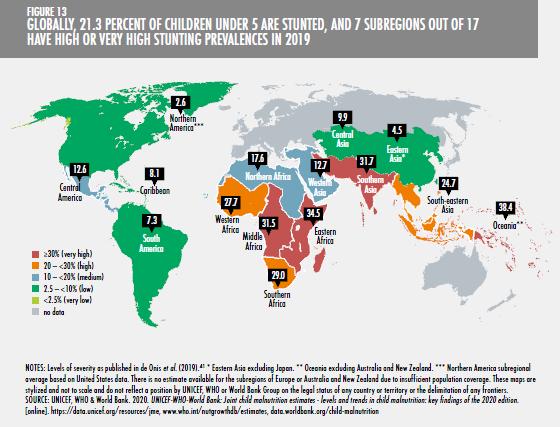

The third document, and in some ways the most surprising, is the 2020 annual report on food security and nutrition from the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). Previous annual reports have painted a cautiously optimistic if not Panglossian picture of progress in reducing hunger, even though the definition of malnourishment used – insufficient caloric intake over a period of at least a year – has been widely and rightly criticised as having little relevance to the real world. This year’s report represents a remarkable turnaround, with FAO conceding that: ‘Two billion people, or 25.9 percent of the global population, experienced hunger or did not have regular access to nutritious and sufficient food in 2019’. The continued prevalence of stunting alone is a powerful argument for more attention to diet in global health.

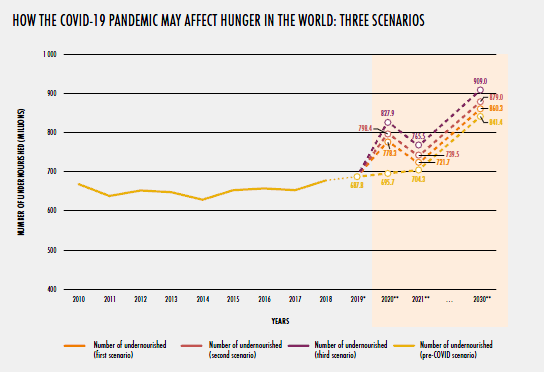

Further, it explicitly considered issues of the affordability of three reference diets (energy sufficient, nutrient-adequate, and healthy), concluding that: ‘Healthy diets are unaffordable to many people, especially the poor, in every region of the world. The most conservative estimate shows they are unaffordable for more than 3 billion people in the world. Healthy diets are estimated to be, on average, five times more expensive than diets that meet only dietary energy needs through a starchy staple. …. [A}round 57 percent or more of the population cannot afford a healthy diet throughout sub-Saharan Africa and southern Asia’. Perhaps most disturbingly, it concluded that even on its earlier, inadequate and ultra-restrictive definition of undernourishment, under any scenario the number of undernourished people will increase between now and 2030.

There is more, much more, to be said, and no summary can do justice to these data-rich sources. In another conceptual step forward, each explicitly addresses climate change, with reference not only to impacts on food production but also to food systems’ (substantial) contribution to greenhouse gas emissions. I’ll be using them all in postgraduate teaching this academic year, hoping they herald a longer-term shift in how food systems are addressed in global health research and policy. And I am not inclined to hopefulness on such matters.