The title of this post is not at all original. Rather, it is the title of a book co-edited with his son by the thoughtful former head of Canada’s public service, Alex Himelfarb (after his retirement). In a newspaper column published at the time, Dr. Himelfarb described the book as an effort to correct the ‘dangerously distorted’ discourse surrounding tax policy, as a result of ‘the neo-liberal economic policy that began to dominate American and British politics in the early 1980s, and emerged more slowly and subtly in Canada at around the same time’. Almost a decade on, the discourse remains distorted throughout much of the world, with increasingly serious consequences for inequality and quite probably for social stability.

Exhibit A is the dire state of Canada’s and the United Kingdom’s tax-financed health systems. (Although the National Health Service and Canada’s multiple provincial and territorial health systems are financed from general tax revenues and are mostly free at the point of use, they are otherwise quite different.) That similarity is arguably why both countries are facing a crisis in access to care, worsened by the effects of Covid-19, that has demonstrably had fatal consequences. Whilst users quite rightly and understandably want health systems to provide necessary care in a safe and timely fashion, resistance to the taxes necessary to finance not only the direct provision of care but also such strategically critical activities as training doctors and nurses has generated political paralysis.

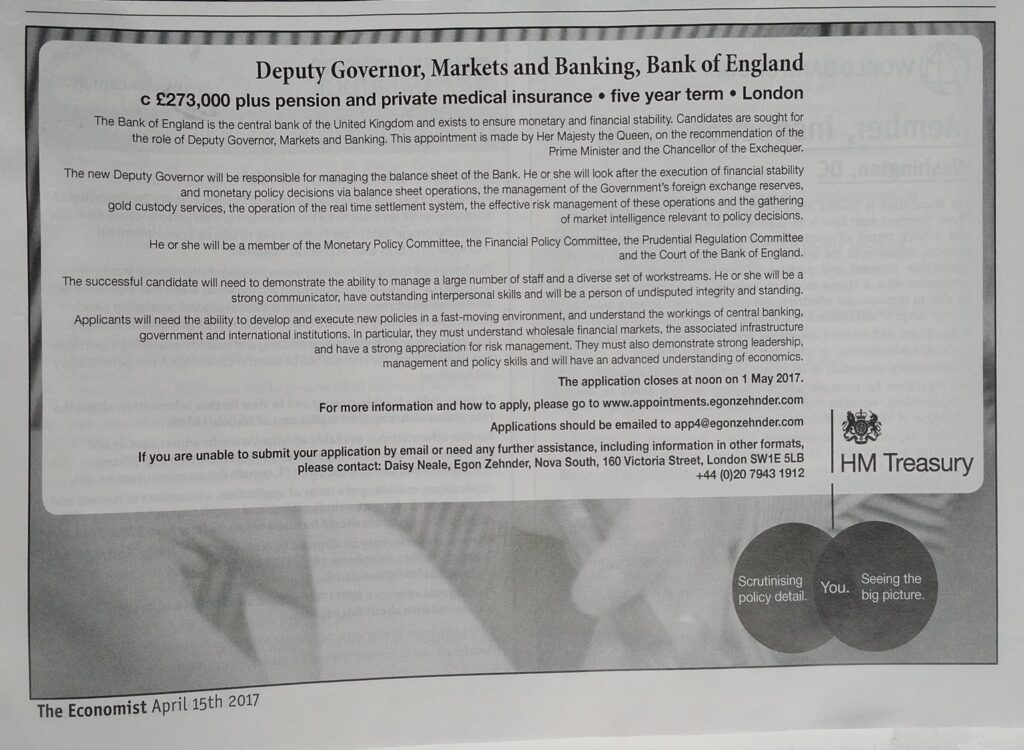

The explanation was succinctly stated around the same time the Himelfarbs’ book appeared by Robert Evans, the magnificently acerbic dean of Canadian health economists: ‘[A] well-functioning modern health system requires the transfer, through taxation, of a very significant amount of money from the healthy and wealthy to the care of the unhealthy and unwealthy’. When we hear arguments that the NHS or Canada’s systems of health finance are ‘unsustainable’, this is code for saying that the richest members of those societies do not want to pay for the care of those presumptively undeserving others. This problem is especially acute in the UK, where the rich have the option of buying private insurance or paying directly for care – something not available within Canadian borders outside the renegade province of Québec. By 2017, HM Government was conceding the inadequacy of the NHS for treating the great and the good (see below).

Such problems are compounded by what is perhaps best described as a lack of policy literacy among the health care and public health community, who often remain unfamiliar with such basic concepts as progressive and regressive tax and spending patterns (and in public finance these terms have a technical, not a normative meaning). Chapter 6 of David Byrne’s recent book Inequality in a Context of Climate Crisis after COVID provides a superb overview, and it – or something like it – ought to be a required part of all university public health and health policy curricula.

On, then, to Exhibit B: the catastrophic inadequacy of actual and proposed responses to the energy price crisis created by Putin’s weaponisation of Russian energy exports. Like the equitable financing of a health system, responding to the crisis will require a substantial redistribution of resources from Mr. and Mrs. Range Rover and the corporate treasuries that have been swollen by windfall gains to the majority of UK households that will, based on estimates by the University of York’s authoritative Social Policy Research Unit, be pushed into fuel poverty by the start of the New Year. At this writing, the silence of the public health community has been deafening. Unfortunately, those who will be least hurt by energy price inflation, or who will actually benefit from it, can probably exercise an effective political veto over the degree of redistribution that will be necessary to avoid a humanitarian catastrophe. In this case, the problem is compounded by a tongue-tied political class unwilling to state the obvious: liberal democratic Europe is at war with Russia, and wartime situations demand wartime sacrifices. But that is a posting for another day.