Forgiving Our Fathers (and Mothers): The Role of Adolescence in Crisis Narratives within American Studies and Children’s Literature

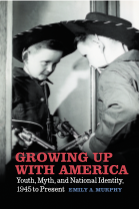

Dr Emily Murphy brings the first in a series of posts exploring the intersections between American studies and children’s literature. The remarks presented here by Julia Mickenberg and Donald Pease are from the launch event for Murphy’s new book, Growing Up with America, which took place on 1 September 2021. This series makes space for continued conversations which Murphy believes the newer field of childhood studies helps to facilitate. The next part of this series will explore more the role of adolescence in shaping and bridging these two fields of study.

In his 1998 film, Smoke Signals, American Indian author Sherman Alexie quotes the poem “Forgiving Our Fathers” by Dick Lourie. One of the main characters in Alexie’s film, an eccentric orphan named Thomas-Builds-the-Fire, asks, “How do we forgive our fathers? Maybe in a dream…Do we forgive our fathers in our age, or in theirs? Or in their deaths, saying it to them or not saying it. If we forgive our fathers, what is left?” The question of how to “forgive our fathers” is one that is relevant to many fields of study, but I’d like to approach it from two fields that are central to my own research: American studies and children’s literature. At the source of the question raised by Lourie’s poem about fathers is an anxiety about the absence left when the tension between and the older and younger generation dissipates: does this lack of tension, often the source of new critical insights in the case of academia, leave the one who forgives feeling empty and uninspired? Or, in forgiving those who came before, are we actually setting ourselves free and escaping the boundaries (disciplinary or otherwise) set by them?

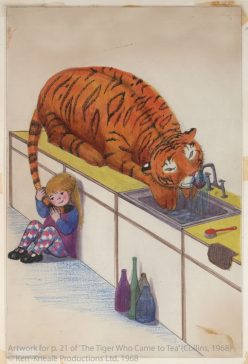

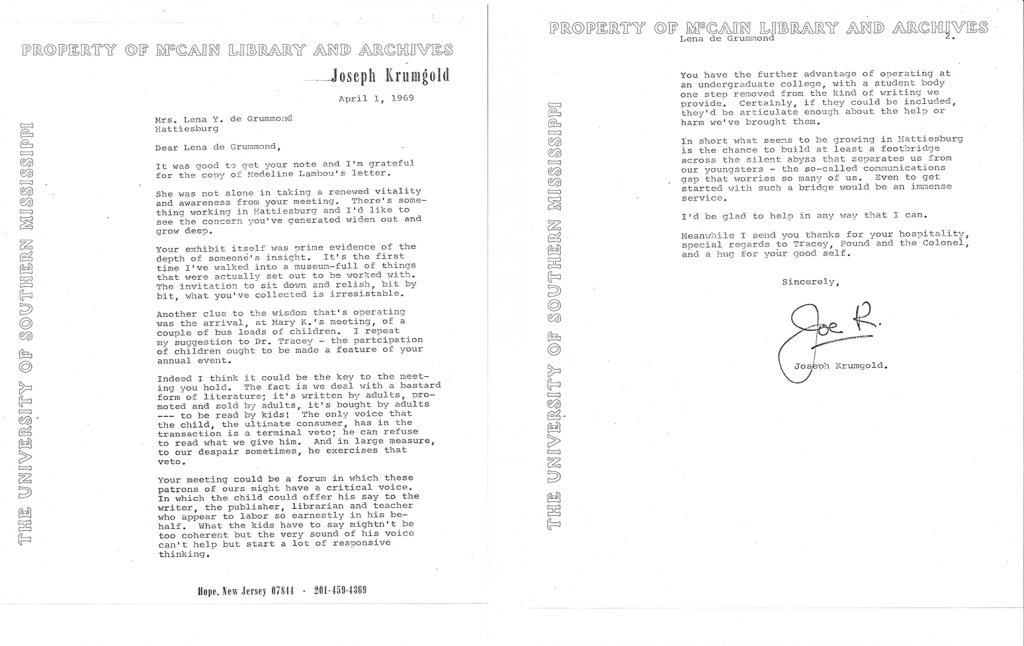

On the one-year anniversary of the publication of my first monograph, Growing Up with America (2020), I had the pleasure of engaging in a dialogue about intersections between childhood studies and American studies with Donald Pease and Julia Mickenberg. Pease, as those in American studies will well know, has greatly contributed to the field as it currently stands, adding to conversations about the “transnational turn” in American studies and opening up new insights into the field as founder/director of the Futures of American Studies Institute and editor of the New Americanists series from Duke University Press. Similarly, Julia Mickenberg is an early advocate for bridging the fields of American studies and children’s literature, drawing our attention to the radical politics in both and recognizing the importance of girlhood, in particular, through her scholarship on Cold War politics. In their commentary on the book, they make a series of important criticisms about the potential risk of the narrative I create in Growing Up with America, which seeks to intervene in the field of American studies by revealing the role of adolescence in the shaping of some of its early history, particularly in the Cold War era when the myth-symbol criticism became popular through the efforts of founding figures that included Henry Nash Smith, Perry Miller, R.W.B. Lewis, and Leo Marx.

What is at risk here, as both Pease and Mickenberg rightfully pointed out, is that in returning to this scholarship we repeat it—something I think that connects to larger conversations about “decolonizing the curriculum” that are happening more broadly within literary studies. This is an argument that American studies has circled back to again and again, and that is most eloquently described in Brian T. Edwards and Dilip Parameshwar Gaonkar’s edited collection Globalizing American Studies (2010), to which Pease also contributes. In the introduction to this collection, Edwards and Gaonkar remark on what they call “founding” and “crisis” narratives, which they view as responses to some of the central currents of “disciplinary anxiety” within the field. They define these two types of narratives as follows: the founding narrative employs a metacritical approach whereby either new objects of study and/or methods of studying these objects are put forward; in the case of the crisis narrative, however, a “discursive rather than performative” mode is more common. This type of narrative is metacritical in a way that is distinct from that of founding narratives, and on occasion uses these founding narratives as a springboard for its insights (8). Edwards and Gaonkar give the example of Amy Kaplan’s influential essay, “Left Alone with America” (1993), where she first analyses the intellectual impulses in myth-symbol critic Perry Miller’s preface to the Errand into the Wilderness (1956). However, in returning to the founding myths of America that Miller deploys in his scholarship, Kaplan also “unwittingly reinstalls exceptionalism” by failing to locate the United States in a global framework (Edwards and Gaonkar 9). It is a classic conundrum, in the sense that by returning to foundational texts, even without intention, scholars take the risk (and I am guilty of this myself) of letting these voices and the narratives they promote continue to have dominance.

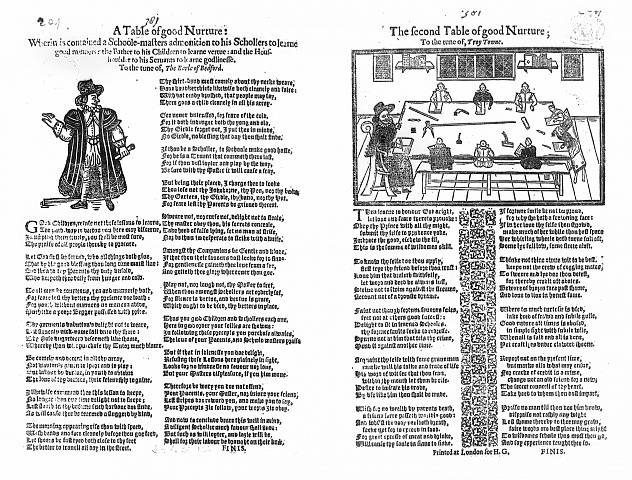

We have seen a similar critical turn within children’s literature, whose own founding narrative begins with figures such as Jacqueline Rose. Rose, who famously declared that “children’s fiction is impossible”—by now one of the most-cited phrases within children’s literature criticism—was preoccupied with language, fantasy, and desire, in large part due to her own investment in Lacanian theory (1). Rose launched a set of disciplinary anxieties specific to children’s literature that continue to permeate the field, in a manner similar to the myth of American exceptionalism which plagues American studies. How, those in the field of children’s literature continue to ask themselves, can we take account of the power dynamics between adult and child in the production and consumption of children’s fiction? And, more recently, to what extent does the child have a say in all of this? A special anniversary edition of Children’s Literature Association (ChLA) Quarterly from 2010 offered a “return to Rose,” but far more insightful are critical essays that attempt a more daring paradigm shift, breaking from Rose’s limiting critical lens for interpreting childhood and children’s literature. I am thinking, for instance, of Marah Gubar’s wonderful essay “Risky Business: Talking about Children in Children’s Literature Criticism” (2013), where she discards what she calls the “difference” and “deficit” models of childhood in favor of a more flexible model of growth—the “kinship model”—that rejects the binary opposition of adult/child altogether (450).

While American studies has yet to locate the child within the field to this extent, there are some interesting moments of critical overlap. Rose, for example, appears in Pease’s influential study The New American Exceptionalism. Here, though, Pease is not looking to her famous work on children’s fiction, The Case of Peter Pan, but rather to her later work on the role of fantasy in relation to English studies in States of Fantasy (1998). Rose’s interest in a psychoanalytic approach to fantasy remains, over ten years after the publication of her study on children’s fiction, and Pease utilizes this scholarship to talk about what he calls the “state fantasy” of American exceptionalism (7). Similarly, in Beverly Lyon Clark’s Kiddie Lit, which is still a definitive history of the field, American studies enters into her argument about the marginalization of children’s literature and childhood. Here, Clark remarks on the way in which, if it did enter the conversation, childhood was simply a reflection on adolescent rebellion in a larger narrative of manhood promoted by the early proponents of American studies (67). In reflecting, then, on founding myths, it is perhaps these moments where one field enters into the other that provides the richer context for the role of childhood and adolescence in shaping American culture and literary thought. As Julia Mickenberg raises in her observations about the shifting academic landscape at the annual American Studies Association meeting, there is now a significantly larger group of children’s literature scholars who have been drawn and converted to the insights offered by American studies. I am certainly a good example of this having trained in children’s literature and only having come to the scholarship of American studies in 2012 after passing my PhD exams and embarking on my dissertation project, which is the early version of Growing Up with America.

So where does this leave us in terms of the founders? Firstly, there is the question of who constitutes as a founder? Is it the “fathers” of the myth-symbol school? Is it a founding “mother” such as Jacqueline Rose—a mother, importantly, who abandoned her “child” (if we continue with the familial metaphors) of children’s literature? And, importantly, in casting ourselves as “fathers” or “mothers,” “sons” or “daughters,” are we doing a disservice to children, who we employ metaphorically to create narratives of progress about these academic fields of study? (I am thinking, for instance, back to the 2010 issue of ChLA Quarterly I mentioned earlier, where Perry Nodelman quips about the “possibility of growing wiser,” in a play on Rose’s famous quote on children’s fiction). The truth is that both fields are continually being founded and refounded, and this isn’t because American studies or children’s literature has “grown up” into a new, mature self—that would do a disservice to children who we are then casting as immature and naïve. Instead, we might take our clue from childhood studies and the models of growth, such as those I have cited here, that seek to disrupt such linear narratives of progress and maturation. In doing so, even if we cannot completely escape it, we might be able to alleviate some of the disciplinary anxieties at the root of both fields and break the cyclical pattern of a return to the founders that limits the boundaries of them.

Works Cited

Clark, Beverly Lyon. Kiddie Lit: The Cultural Construction of Children’s Literature in America. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2003. Print.

Edwards, Brian T., and Dilip Parameshwar Gaonkar, eds. “Introduction: Globalizing American Studies.” Globalizing American Studies. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2010. 1–44. Print.

Gubar, Marah. “Risky Business: Talking about Children in Children’s Literature Criticism” (2013).

Nodelman, Perry. “Former Editor’s Comments: Or, The Possibility of Growing Wiser.” Children’s Literature Association Quarterly 35.3 (2010): 230–242. Print.

O’Brien, Sharon. “Commentary.” In Locating American Studies: The Evolution of a Discipline. Ed. Lucy Maddox. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999. 110–113. Print.

Pease, Donald. The New American Exceptionalism. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2009. Print.

Rose, Jacqueline. The Case of Peter Pan. 1984. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1992. Print.

Smoke Signals. Dir. Chris Eyre. Miramax Films, 1999. DVD.