The Occasional Diary of a Mature Postgraduate Student at Newcastle University’s Children’s Literature Unit

Jennifer Shelley

Episode Four

On realising I know nothing – but am starting to learn

There’s a rather lovely sense of back-to-school in Newcastle at the moment: there’s an autumnal chill in the air, the leaves are turning and I’ve bought some splendid new shoes.

It’s the start of the new academic year, and for me, as a research student, it’s also the end of the old one, which technically finished mid-September when I had to submit the third and last research assignment of my first year.

In one sense it seems like yesterday that I started the MLitt in children’s literature as a mature student; in another, it feels like a lifetime (largely in a good way). As mentioned in previous blogs, I’m taking the course over two years, as a part-time student, so this is essentially the half way point for me.

So what have I learned?

The first and possibly most important thing for me was not to underestimate just how much there is to learn: many years as a keen reader of children’s books are certainly not a passport to academic success. There’s a song by Dean Friedman from the 1970s where the chorus goes something like you can thank your lucky stars that we’re not as smart as we like to think we are. It’s not a track I ever particularly liked, but unfortunately it’s been going round and round in my head, almost since my first meeting with my supervisor, and certainly since I started getting feedback on my work. It turns out that academics can be – how can I put this? – blunt in asserting their opinion of one’s hard-sweated efforts, and any notion that I’d walk in being brilliant was quickly dispelled.

The second lesson was somewhat connected, in that it involved a growing appreciation that challenge and criticism is not only good in a ‘swallow-your-medicine’ kind of way, but that it can also be thoroughly enjoyable. It can be disconcerting at first to be forced to justify everything you say or write (at some points when asked why I’d included mention of a particular critic, for example, I just wanted to wail ‘well I don’t know, it just seemed a good thing to write’). But actually, being forced to anticipate that kind of challenge has made me much more stringent in my own writing, both in my academic and professional life.

And that’s probably the nub of the third lesson: academic writing is a skill in itself. Having been a journalist for almost three decades, freelance for half of that, I’m accustomed to writing for a variety of different audiences from the general public to policy-makers and specialists. Before I started this degree, I was aware that I’d have to abandon some of my most dearly-held tenets, such as never writing an introductory sentence of more than 30 words; I also knew that I’d have to get to grips with proper referencing. But I had thought less about other aspects of academic writing, from the simple (such as not using contractions) to the harder-to-judge, like avoiding colloquialisms. In each of the three research assignments I’ve submitted, I’ve been picked up for using informal language, even though I’ve tried very hard to stamp it out in my writing.

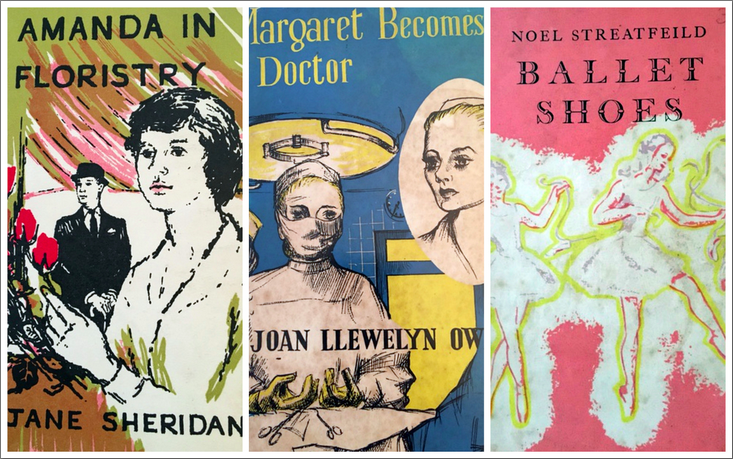

Has it been worth it? Well, I have to say I’ve absolutely loved it, challenges and all. It’s been possibly harder than I anticipated to balance my professional life and university life (not to mention life-life and all its inevitable issues), but it as also been hugely satisfying. I’ve genuinely had a sense of progression, not just because my marks have steadily grown higher over the course of the year, but because I can see myself that while my work still has an enormous way to go, it’s definitely improving. In case anyone’s interested, my research topics covered my existing interests – mid-twentieth century books for girls – but through a lens that was new to me, that is, the feminine middlebrow. The first essay was on career novels for girls, the second on the family novels of Noel Streatfeild, and the most recent on Mabel Esther Allan’s coming-of-age novels, specifically the Drina series (written under the name Jean Estoril).

So now it’s time to plan the dissertation – probably in itself the topic for another blog – and to jump in to my second and final year as a mature student. I’m looking forward to it very much – and did I mention I’ve got some great new shoes?