Philippa Carter is a third year PhD student in the School of Geography, Politics and Sociology at Newcastle University. Here she tells us about her recent community project in Chopwell village.

My PhD research at Newcastle University explores landscape and intergenerational memory in the context of the Land of Oak & Iron Heritage Project, which focuses on the Derwent Valley, North East England. I recently secured funding from the Challenge Labs scheme, which is run by Newcastle’s Humanities and Social Science Faculty’s three Research Institutes (Humanities, Social Science, Creative Arts Practice) and is designed to support interdisciplinary approaches to particular research ‘challenges’. As part of the application process I was introduced to Carole McCourt, an MA student in Fine Art, and we collaborated on our projects, both of which focus on the importance of place. Carole’s project is based at Cheeseburn in Northumberland and the collaboration was a real bonus for the project as it widened the scope of my thinking. We worked collaboratively to develop and evaluate our projects and having a ‘critical friend’ to question ingrained ways of thinking was invaluable.

The village of Chopwell is one of my research case studies. The Land of Oak & Iron project focuses on a 177 km2 area encompassing parts of Gateshead, County Durham and Northumberland. The former pit village of Chopwell was built at the turn of the twentieth century to provide coal for Consett Iron Company and is located at the centre of the project area adjacent to a large ancient woodland. ‘Oak and iron’ are, therefore, integral to its history and character. I have thoroughly enjoyed working in Chopwell and villagers have been extremely helpful, providing me with a huge amount of material from interviews and walks and welcoming me at community meetings and events. It has been absolutely fascinating to discover the history of the village and I developed a Challenge Labs project which aimed to celebrate this history and to ask ‘how can memories of Chopwell’s past provide a vision of the future?’ My project focused on the social life of the village and therefore I was mainly thinking about how people have shaped place. Carole’s work involved researching the physical and geological features of her site and she has gone on to create artwork which captures physical traces of these elements. I was able to learn from the way Carole approached her research from the perspective of another discipline, which led me to think more about how the natural environment impacted on the development of the village.

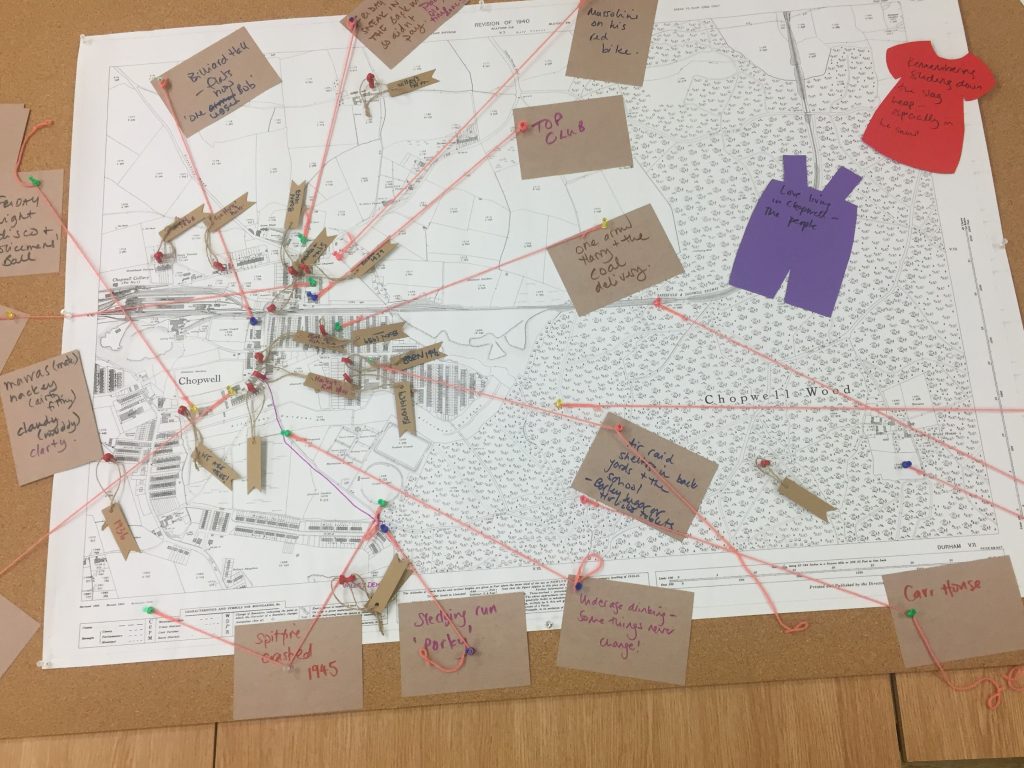

I created a small exhibition on the history of the village, with a focus on local social life. I did this through archive research and the creation of a Facebook page which allowed me to interact with local people and collect their memories of places like pubs, fish and chip shops and cinemas. Chopwell was once a bustling local hub and I hoped to go some way to capturing the essence of the social interactions hosted in these places whilst enabling people to connect with each other in the present. I then organised an event at Chopwell Community Centre which was based around an interactive map (a large printed copy of the 1940 Ordnance Survey map with labels and pins) on which I asked people to mark their home and a place which held special memories for them. This process opened up a wide ranging (and very entertaining!) conversation, with people staying to chat for long periods of time and connecting or re-connecting with others from the village. In some cases people who had been classmates in school had their first conversations in 50 or 60 years. What really struck me about this was how time seemed to fall away as people chatted and the memories that they shared brought them together and enabled easy conversation between virtual strangers.

Responses to this activity suggest that heritage can be used as a positive means of imagining and shaping the future in a very practical ‘bottom up’ sense. Much of the detail of the discussion could be described as tinged with nostalgia, as people reminisced about their childhoods and lost features of the village. However, it became clear that talking about the past was making a tangible difference for some. One group of older men had come along as they had reconnected with one another at a different heritage event held locally. Some still lived in the village, others had moved slightly further away, but after bumping into each other they began to meet on a regular basis and were starting a ukulele group. One of the men wrote a Facebook post which showed it meant a huge amount to him to reconnect with his friends and to find new ways of socialising and making connections in the community. What to others could seem like a group of people meeting to reminisce in a maudlin way was actually creating new opportunities for all of those involved and using the past as a way of taking their lives forward and improving their everyday lived experience. This kind of memory work feels much more organic than more traditional consultation-style events where people are asked ‘what do you want to change?’ Instead, the events were empowering individuals to make change in their own lives through remembering.

My research explores nostalgia as a creative force, challenging the negative connotations it so often brings. Instead of viewing nostalgia as inherently conservative or backward looking, I would suggest that the real challenge is finding ways to ensure there are positive outlets and opportunities for people to capitalise on these processes of memory, keeping the imaginative process moving forward. This is something I continue to explore as my thesis develops.

The exhibition I created, ‘A Good Night Out in Chopwell’, can be seen at The Lodge Heritage Centre, Blackhill & Consett Park throughout February. You can follow Carole McCourt’s ongoing work at Cheesburn on Twitter @CheeseburnArt