Professor Janice McLaughlin

Professor Janice McLaughlin is a sociologist in the School of Geography, Politics and Sociology and until recently Director of the Policy, Ethics and Life Sciences Research Centre. Her work explores how childhood disability or illness is framed from within the worlds of medicine, community and family. She has looked at themes such as the diagnosis of genetic syndromes in children, the role of medical intervention in the lives and identities of young people with cerebral palsy and the ways in which family lives can be changed, including positively, by the presence of a disabled child. More recently this work has increasingly become focused on questions about citizenship and young people – a shift that has come from working with young people and hearing their concerns about their position in society and their futures.

Working with young people from different backgrounds can be frustrating, challenging and a lot of work. Below I suggest why all of those difficulties are worth it if we are to create spaces where young people have a voice and how we can at least try to do it in ways that work for them. Most of the problems come from the institutional dynamics around children and young people and in themselves present insight into the ways in which society and the state carefully monitor children and their presence in the public realm. While many of these structures have emerged out of previous harms done to children, in themselves they risk producing the social fact that young people are vulnerable rather than being also seen as having the potential and capacity for agency and creativity. Young people can also be very busy, particularly with the demands of schooling (again highlighting the pressures on them from an early age). We have learned the need to be very adaptive to both their timetable and their interests. When a young person’s free time is limited (particularly for disabled young people who are often having to also fit in hospital appointments, surgery, physiotherapy, dealing with welfare agencies, alongside their school life) you need to ensure that if you ask them to give their time that it a) has a point and b) will be interesting to them.

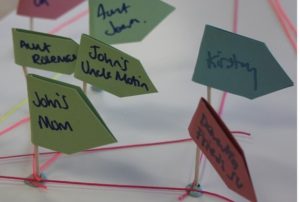

Within a project examining embodiment and disability we explored the use of creative techniques – in particular making things, taking photographs and producing journals – as a way to make things more interesting and relevant to the young people.

Photograph taken by a research participant’s dad to show how he gets downstairs

Piece of jewellery made by a research participant to symbolise the importance of relationships to her

For the young people who participated in that aspect of the project their feedback was that it was very enjoyable and did allow them to express issues around their lives and disability that was meaningful. Mark (none of the names given are people’s real names) represented his pride in his physical strength and ability to find ways to move through space through the picture he had taken of him moving down the stairs. Kim, used the bracelet to symbolise how the relationships around her of friends and family were of vital importance to her and a source of strength to her. So the creative techniques did add something to the project and worked well for those who participated, but here also is the snag, the number of participants who wanted to do these activities in comparison to the usual one to one interview was much less. So while methods papers may suggest that when working with children and young people that we should think about ways to make it more interesting and diverse than a research interview, it is worth checking if that is what young people actually want!

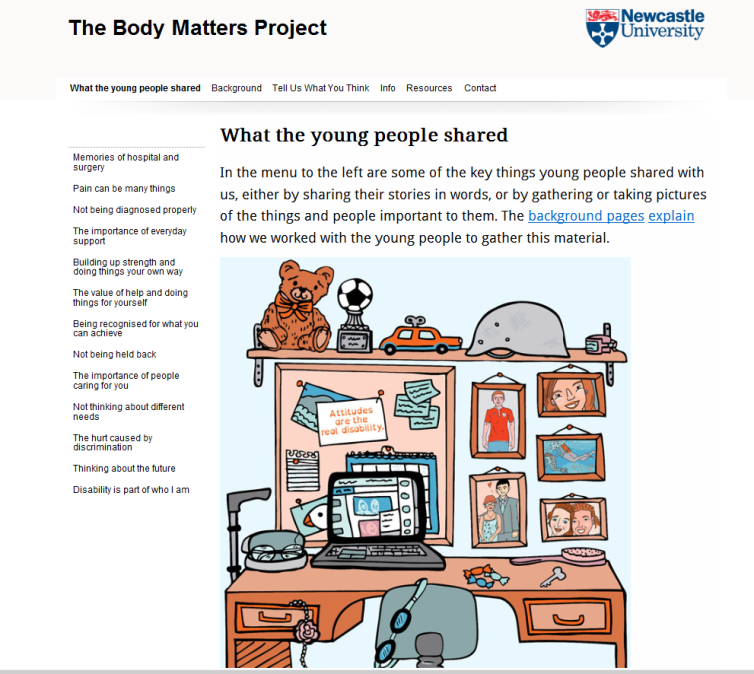

One benefit of the visual material the young people made is it did produce material that was very rich and also very appropriate for taking the findings out to non-academic communities. We worked with a graphic artist, web designer and a group of disabled young people to design a website and booklet that young people could use to explore themes about difference and how society treats children who have something different about them, in this case their bodies. The words and images the young people produced were central to that and the site could not have been developed without their input. The website is now being used by schools, third sector organisations and in teacher training (in New Zealand!).

Screenshot of the website

So to sum up, yes it is worth working with children and young people, it’s obvious really, they have lots to say. But we need to keep thinking through and checking (with them as much as anyone) what the point of doing so is.

Other information:

Open access publications from the project:

McLaughlin, J. and Coleman-Fountain, E. (2014) The unfinished body: The medical and social reshaping of disabled young bodies. Social Science and Medicine. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.09.012

Coleman-Fountain, E. and McLaughlin, J. (2013) The Interactions of Disability and Impairment, Social Theory and Health, 11(2): 133–150, doi:10.1057/sth.2012.21

The research was funded by the Economic and Social Research Council and ongoing work we are doing with young people on citizenship is supported by the Newcastle Institute for Social Renewal.

Other work and resources we have produced on disabled young people’s views on and participation in sport is also available.