Creating videos by putting together clips from a collection of recordings is a time consuming task. Our colleagues in Digital Media help us by providing a rough cut of the raw footage with a hard-baked timestamp on the recording. Our job is to sift through this to find the bits we want. You’ll imagine though that this involves a lot of seeking backward and forward through a video with frequent pauses to note down timestamps. Our colleague Mike Cameron (now at Bristol) battled with this last year and cleverly anticipated that ReCap had the potential to make life easier.

What we want to do is not that dissimilar from a group of students collaboratively annotating a lecture. Things that really help us, like our undergraduate counterparts, are searchable bookmarks, the ability to play content fast (never let it be said that students would ever listen to lecturers at 2x speed), and the ability to rewind.

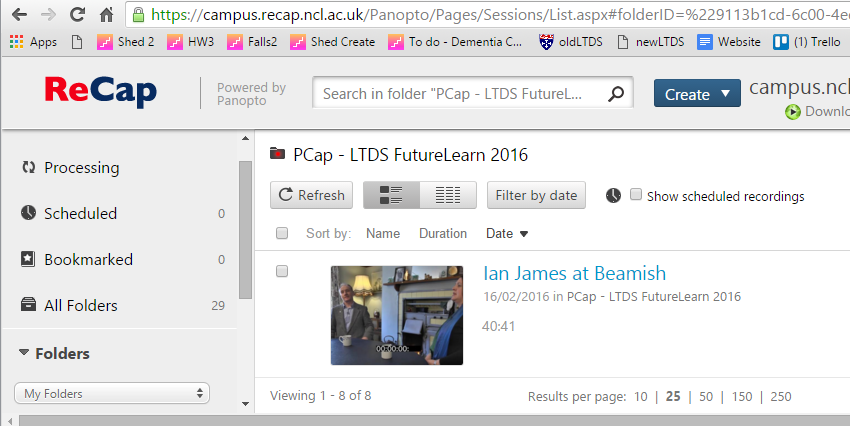

Following a speedy consult with colleagues in team ReCap we requested a PCAP folder with permissions at the folder level for all of the team – that’s Digital Media, LTDS and Academic colleagues.

Uploading video was a doddle using the “Create” button, then we needed some conventions for the “Channel” we planned on using for collaborative notetaking. Channel names aren’t listed (presumably some form of security by obscurity thing) so we decided to name our shared annotations “team” (in lowercase) and to annotate the start of any piece of dialogue with the speakers initials, the topic, and whether the delivery was good. If Nuala Davis gave a poor answer on Widgetology we’d put

ND-widgetology-no

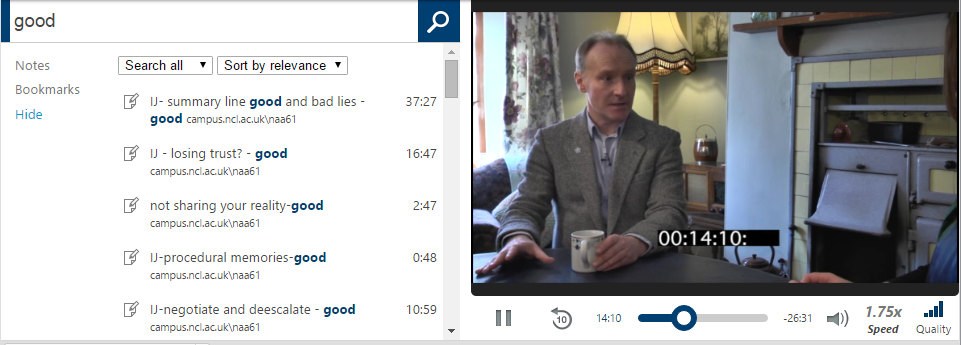

In a 40 minute interview it’s great to be able to scan and jump to the real gen on Widgetology just by clicking on the annotation. By way of example here’s what we get one of our videos using the keyword “good”.

What’s particularly great about this is

- we can jump straight in at particular annotation points without the pain of seeking backwards and forwards.

- Our team annotations are in one place, we’re not struggling to keep up to date with the latest version.

- Because the footage is on ReCap we can get at it anywhere (on and off campus), and we know that only our team can access it, and if we choose to we can permit other campus users viewing rights.

- We can adjust the playback speed to skim through footage (1.5 – 1.75 is workable)

- We can also use private notes to create personal annotations, and when we move between personal notes and shared channel, ReCAP (gloriously) stays at the same timestamp.

And one or two learning points about these channels.

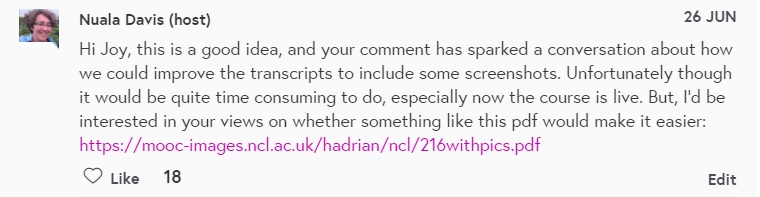

- it’s nice that ReCap shows who has made an annotation, and quite properly, permissions are such that Angela can’t edit one of my notes in our shared channel. If we wished to do this we’d need to sign in to ReCap with a suitable role account used for the project.

- I mentioned that channels aren’t listed. We’ve spotted that they are case-sensitive, so it would be easy for two people to work on “team” and “Team” without twigging that they were duplicating effort.